Somewhere in the dark, quiet reaches of the universe, two invisible giants are circling each other, tightening their orbit in a slow, relentless dance. For millions or even billions of years, they spiral closer, twisting the very fabric of space-time like a cosmic whirlpool. Then, in a fraction of a second, they collide and merge, releasing more energy than all the stars in the observable universe shine in that instant. We cannot see this crash directly, but we can feel its echo as ripples in space-time washing across Earth. The mystery of what really happens in that final moment has gone from abstract theory to a measured, recorded event – and it is reshaping how we think about gravity, time, and even the origin of black holes themselves.

The Hidden Clues in Cosmic Ripples

When two black holes collide, they do not produce light, radio waves, or X-rays that telescopes can easily catch, at least not in most cases. Instead, their most dramatic signature is a tremor in space-time itself, known as a gravitational wave. These waves stretch and squeeze distances by a tiny amount, smaller than the width of a proton over kilometers of space, yet they carry the unmistakable fingerprint of the collision. In 2015, observatories like LIGO first captured such a signal from merging black holes, confirming a prediction that had sat on the theoretical shelf for a century. I still remember reading that announcement and feeling a bit like the universe had finally replied to a question physicists had been shouting into the void for decades.

The shape of those waves encodes the story of the crash. The early, lower-frequency curve traces the long, slow inspiral as the black holes orbit each other, gradually losing energy. As they draw closer, the pitch rises, like an ambulance siren winding up, until the final violent merger produces a brief, sharp burst. After that, the newborn, larger black hole “rings” and settles down, leaving behind a damped signal that fades into silence. By decoding this pattern, scientists can estimate the masses, spins, and even the distance of the colliding black holes, turning a fleeting cosmic tremor into a detailed forensic report of an event that happened billions of years ago.

Inside the Final Dance of Two Black Holes

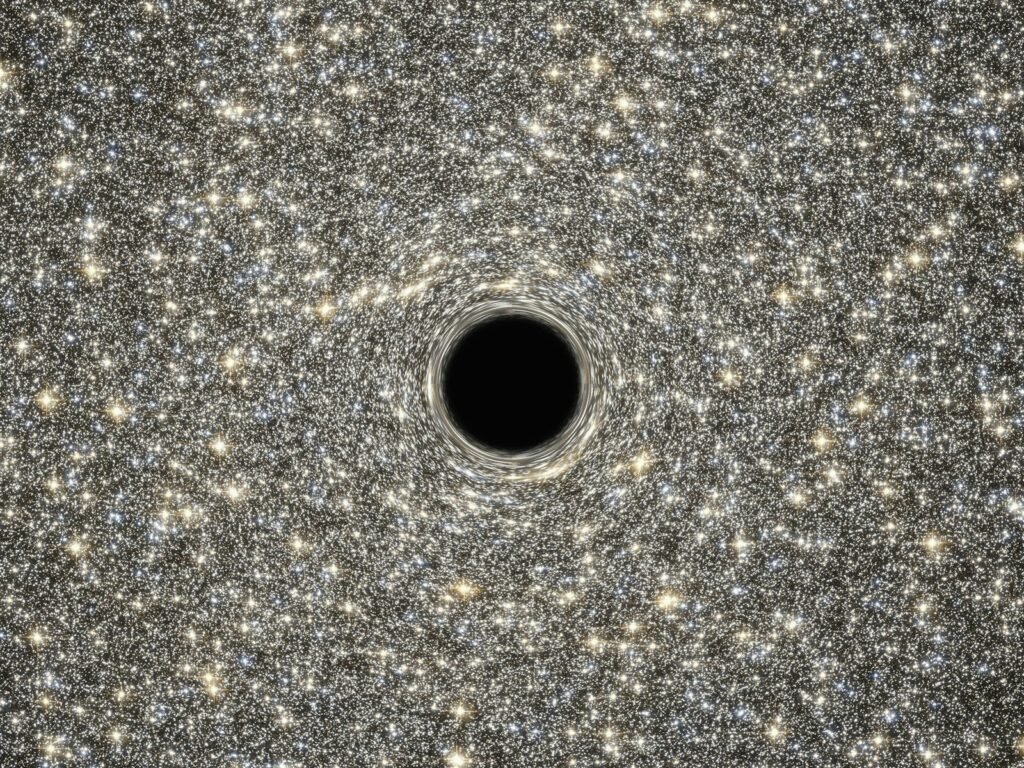

It is tempting to imagine two distinct objects slamming into each other like billiard balls, but black hole collisions are much stranger than that. As the pair spirals inward, their event horizons – the boundaries beyond which nothing escapes – begin to distort and stretch. Space around them becomes a churning ocean of warped geometry, where orbits loop and twist in ways that defy everyday intuition. In their last few orbits, they can circle each other dozens of times in the span of a second, moving at speeds approaching that of light. All the while, they are radiating away enormous amounts of energy as gravitational waves, shrinking the orbit like a cosmic brake.

At the moment of merger, the two horizons fuse into one larger horizon in a surprisingly smooth process, at least from the perspective of the mathematics. There is no explosion in the traditional sense – no blast of matter since almost all of the mass is already hidden behind the horizons. Instead, the violence is in the structure of space-time itself, which briefly becomes highly distorted before relaxing. Simulations show this as a kind of wobbling, ringing bell of gravity, radiating away the last wrinkles in a pattern sometimes called the ringdown. The final black hole is typically a bit less massive than the sum of its parents, because a small fraction of the total mass – often a few times that of our Sun – is carried away as pure gravitational-wave energy in an instant.

From Wild Theory to Measured Reality

For most of the twentieth century, the idea of two black holes colliding lived primarily in the realm of equations and thought experiments. Even some experts quietly wondered whether nature would actually produce such systems in measurable numbers. That changed when detectors like LIGO in the United States and Virgo in Europe became sensitive enough to spot minuscule distortions in space-time. What surprised almost everyone was just how often the universe seems to stage these collisions. Instead of being rare curiosities, mergers of black holes turned out to be happening frequently enough that new events are now logged on a regular basis.

This flood of detections has pushed black hole science from speculation into data-driven astronomy. Researchers can now catalog black hole masses across many events, revealing patterns that hint at how these objects formed. For example, some collisions involve black holes much heavier than those expected from typical dying stars, nudging theorists to refine their models of stellar evolution and supernova explosions. In a way, gravitational wave observatories have become a new kind of telescope – one that listens instead of looks, giving us a view of the universe that would have been completely inaccessible with light alone. That shift from “can we detect one?” to “what can we learn from dozens?” marks a major turning point in modern astrophysics.

Shocking Energy on a Human Scale

The energy released when two black holes collide is staggering, but the numbers can feel abstract until you translate them into something more familiar. In a typical merger, a few solar masses are converted into gravitational-wave energy in a fraction of a second. If even a tiny portion of that were somehow converted into electricity, it would dwarf all the power humanity has ever generated. And yet, by the time those waves reach Earth, after traveling for hundreds of millions or billions of light-years, they are so faint that they move LIGO’s mirrors by less than a thousandth of the diameter of a proton. It is like detecting the motion caused by a gentle breeze in one galaxy using a wind chime in another.

That contrast – enormous power at the source, almost unimaginable subtlety at the detector – is part of what makes these discoveries so impressive. It also shows how intertwined technology and fundamental physics have become. To measure black hole collisions, engineers had to build some of the most precise instruments ever created, capable of filtering out truck traffic, earthquakes, and even the quantum jitter of light itself. The fact that those instruments actually see anything at all is a reminder that human ingenuity can reach across absurd distances and interact with events that happened long before our species even existed. In a sense, every detection is a quiet, delayed handshake with a distant, violent past.

Why It Matters: Rethinking Gravity and the Universe

At first glance, it might seem like black hole collisions have little to do with everyday life on Earth. We are not going to be swallowed by a nearby merger, and no one is building a gravitational-wave power plant. But scientifically, these events are a stress test for our deepest theories about how the universe works. General relativity, our current theory of gravity, makes very specific predictions about the shape and timing of gravitational waves from a merger. So far, observations have matched those predictions with impressive accuracy, reinforcing a theory that has stood for over a hundred years. That said, researchers are keenly watching for even tiny deviations that might hint at new physics, such as quantum effects or extra dimensions.

Black hole mergers also give us a new way to probe cosmic evolution. By counting how many collisions occur at different distances – and therefore different times in the universe’s history – astronomers can trace how often massive stars formed and died, how galaxies interacted, and even how clusters of stars assembled. These events act as “standard sirens,” helping measure how fast the universe is expanding when paired with other observations. In that sense, every collision is more than just a dramatic story; it is a data point in a much bigger narrative about how the cosmos has changed over billions of years. Without them, our picture of the universe would be missing a key dimension of depth.

Messy Origins: Where Do These Black Hole Pairs Come From?

One of the liveliest debates in current astrophysics is how pairs of black holes come to be in the first place. A straightforward scenario is that they started as two massive stars born together in a binary system, each ending its life in a collapse that leaves behind a black hole. Over time, they spiral closer under the influence of gravitational radiation until they finally merge. But many events detected so far suggest that some pairs did not follow such a simple, quiet life. Their masses and spins hint that they may have formed in crowded environments such as star clusters, where chance encounters can pair up objects that were never “meant” to be together at birth.

There is also the intriguing possibility that some black holes formed very early in the universe, perhaps even from dense regions right after the Big Bang rather than from stars. If those so-called primordial black holes exist and sometimes collide, their signatures might look slightly different from those of more ordinary, stellar-born black holes. Sorting out which collisions fit which origin story is a bit like doing genealogy with only a handful of genetic markers. Each new detection helps, but the full family tree is still a work in progress. The messy, overlapping possibilities are part of what makes this field so alive; nature is not obligated to choose just one formation path, and the data suggest it probably has not.

The Future Landscape: Sharper Ears and Deeper Questions

The current generation of gravitational wave detectors has already changed physics, but they are really just the beginning. Planned upgrades on Earth-based facilities will make them more sensitive, able to hear quieter and more distant mergers that are currently lost in the cosmic background noise. Beyond that, space-based observatories such as the planned LISA mission aim to place detectors millions of kilometers apart, listening to lower-frequency waves from supermassive black holes at the hearts of galaxies. These titanic collisions could reveal how galaxies grow and interact over cosmic time, opening another new window into deep space. It is a bit like going from hearing only nearby thunderstorms to also detecting the rumble of distant, slow-moving tectonic shifts.

With more data will come new challenges. Distinguishing overlapping signals, dealing with instrumental noise, and interpreting complex waveforms will all require advanced analysis tools and perhaps new mathematical tricks. There is a real possibility that future observations will uncover events that do not fit current models at all – mergers that are too massive, too asymmetric, or too oddly timed. Those outliers could be where hints of new physics or exotic objects first appear. At the same time, the growing gravitational-wave network will increasingly rely on international cooperation and long-term funding, making this not just a scientific adventure but a political and social one as well.

How You Can Stay Connected to a Colliding Universe

It is easy to feel distant from black hole collisions, given that they happen in environments we will never visit, on timescales far beyond a human lifetime. Yet there are surprisingly concrete ways for non-specialists to stay involved in this unfolding story. Many gravitational-wave observatories make their detection alerts and some of their data public, meaning interested readers can track new events almost in real time. Educational resources, visualizations, and even interactive tools now let you explore how changing the masses or spins of black holes affects the signals we detect. Following these developments turns abstract physics into an ongoing narrative you can actually watch evolve.

If you want to go a step further, citizen science platforms sometimes host projects related to gravitational waves and related astronomy, asking volunteers to help classify simulated events or identify features in large datasets. Supporting science-friendly policies and funding, even just by paying attention to public discussions about research investment, also has a direct impact on how quickly fields like this advance. And perhaps most importantly, talking about these discoveries – sharing them with friends, teachers, or kids – helps keep curiosity alive in a world that often feels weighed down by more immediate concerns. In the end, every black hole collision we detect is a reminder that the universe is dynamic, surprising, and still full of unanswered questions. Paying attention to that cosmic drama is one of the simplest, and most powerful, ways to stay connected to something far bigger than ourselves.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.