Vermont’s majestic moose are facing an unprecedented battle for survival, and their enemy is smaller than your pinky nail. In the forests of the Northeast Kingdom and beyond, these iconic giants are losing a war against that’s reshaping the state’s wilderness. What was once a manageable parasite-host relationship has become a devastating ecological crisis that threatens not just individual animals, but entire populations. The situation has become so dire that biologists are documenting “ghost moose” – emaciated animals rubbed nearly bald from trying to scrape off tens of thousands of blood-sucking ticks. In Vermont, the population has declined significantly in recent years despite minimal hunter harvest and adequate habitat. The culprit behind this decline isn’t habitat loss or hunting pressure, but climate change creating perfect conditions for tick explosions that are literally bleeding moose populations dry.

The Tiny Terror: Understanding

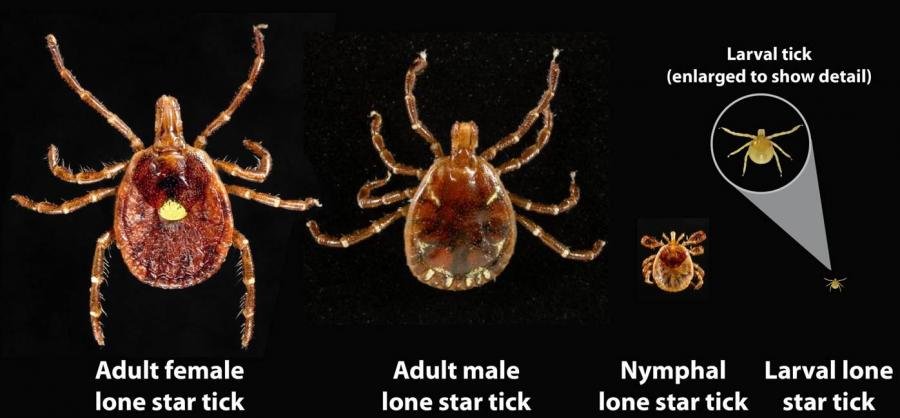

, scientifically known as Dermacentor albipictus, aren’t your typical backyard pest. , also known as moose ticks, typically feed on the blood of large mammals and cause stress and mortality for moose populations across the U.S. Unlike other tick species that jump from host to host, these parasites are single-host specialists, meaning they latch onto a moose and stay there for months. The life cycle of a winter tick is perfectly synchronized with nature’s calendar. The life cycle of begins with females laying eggs near the soil surface in June. Each female can produce several thousand eggs which hatch between August and September. What makes these creatures particularly dangerous is their hunting strategy. These larvae have interlocking limbs allowing one tick that manages to attach to a passing moose to bring along hundreds or thousands of ticks looking for a host. It’s like a biological nightmare where catching one means catching thousands.

Climate Change: The Perfect Storm

Vermont’s changing climate has turned what was once a natural balance into a deadly imbalance. “A warming climate creates more opportunities for to thrive, less snow cover allows the females to come in contact with more suitable ground conditions, increasing the chances of them laying eggs adding to the next generation of ticks.” The math is simple but devastating: warmer weather equals more ticks equals more dead moose. Historically, Vermont’s harsh winters were nature’s way of keeping tick populations in check. In the past, after long New England winters that lasted well into April, the ticks would jump off moose, hit spring snow, and die. But warmer, shorter winters means those ticks are more likely to land on bare, snowless ground, which lets them live another day – and possibly flourish. Climate data supports this alarming trend. Since 1970, average annual maximum temperatures in New Hampshire have warmed 0.5 to 2.1 degrees Fahrenheit – with the greatest warming occurring during the fall and winter. The timing couldn’t be worse for moose. For , warmer summer temperatures are associated faster development of eggs into larvae and increased egg survival. It’s a perfect storm where climate change accelerates every stage of the tick lifecycle while simultaneously weakening the natural barriers that once protected moose.

The Birth of Ghost Moose

Perhaps no image captures the severity of this crisis better than the phenomenon of “ghost moose.” It’s a telltale sign that the calf was becoming a “ghost moose” – an animal so irritated by ticks that it rubs off most of its dark brown hair, exposing its pale undercoat and bare skin. With their skinny necks, emaciated bodies, and big, hairless splotches, these moose look like the walking dead as they stumble through the forest. The transformation from healthy moose to ghost moose is both heartbreaking and scientifically fascinating. The tick-infested animals are called “ghost moose” because in an attempt to dislodge the ticks they scratch, bite, and rub at their fur, exposing a pale undercoat and bare skin. This desperate grooming behavior becomes an obsession that consumes precious energy. Once ticks are feeding on it, though, this brief routine can become a two-hour ordeal that consumes a higher percentage of its waking hours. This takes a lot of energy – and time away from finding food and eating. The visual impact of seeing a ghost moose in the wild is profound. It was spring 1992, near the town of Lewis in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, when Cedric Alexander saw his first ghost moose. “I was in the woods doing a spruce grouse breeding survey,” says Alexander, a wildlife biologist for the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department. Since then, these ghostly appearances have become increasingly common across Vermont’s forests.

Death by a Thousand Bites

The sheer number of ticks that can infest a single moose defies belief. A single moose can carry over 40,000 ticks and have caused over 90 percent of moose calf mortalities in Vermont in recent years. In extreme cases, the numbers become astronomical. It’s not uncommon for biologists or hunters to find moose infested with 40,000, 75,000 or even 90,000 ticks. Some research has documented even higher infestations, with a study group found one moose calf to have over 90,000 ticks. Each tick is a tiny vampire draining the life from its host. Each adult female winter tick can remove one milliliter of blood from its host, which adds up to gallons of blood when you’re talking tens of thousands of ticks. Replacing that much blood may be impossible for some moose – particularly a pregnant cow – while subsisting on fat reserves and little else during winter. The physiological toll is devastating. Blood consumption by ticks often leads to chronic anemia, protein deficits, and substantial energetic costs for moose. The timing of tick feeding coincides with the most vulnerable period in a moose’s annual cycle. “They’ve used up their reserves over the winter, then they have all these insects biting them, making them itch, draining their blood supply, and generally making them miserable.” It’s like being forced to give blood donations while running a marathon in the middle of winter.

Vermont’s Calf Crisis

The impact on Vermont’s moose calves has been catastrophic. 87% of adults survived each year, but only 57% of adult cows gave birth, a decline of around 50% compared to birth rates in the early 2000s. Only 66% of newborn calves survived their first 60 days. Only 49% of calves (8-12 months old) survived their first winter. These statistics tell a story of a population in free fall. The research paints an even bleaker picture when ticks are factored in. With no ticks, over 90% of calves would have survived. were the main cause in 74% of all mortalities and 91% of winter calf mortalities. In some recent years, the situation has become even worse. In one recent winter, around sixty-three percent of moose calves in Vermont died, the highest figure on record. Young moose are particularly vulnerable because they haven’t developed the body mass and strength to withstand massive tick infestations. Observed adult survival was 90% in 2017, 84% in 2018, and 86% in 2019, and winter calf survival was 60% in 2017, 50% in 2018, and 37% in 2019. The declining trend in calf survival over this three-year period shows how the crisis is intensifying.

The Vermont Population Collapse

Vermont’s moose population has experienced a dramatic decline that mirrors the tick explosion. Vermont’s moose herd has decreased from an estimated high of over 5,000 individuals in the state in the early 2000s to roughly 2,200 today. This represents more than a fifty percent reduction in just two decades, a collapse that would be shocking for any wildlife population. The geographic distribution of Vermont’s moose reveals the complexity of the crisis. Based on current (2022) population estimates, a little more than half of all moose in Vermont live in WMU E. The density (2021–2023 rolling average) estimates in WMU E1 and E2 is 1.29 and 1.56 moose per square mile, respectively. This concentration in the Northeast Kingdom creates a perfect storm for tick transmission. Ironically, the area with the best moose habitat is also where they face the greatest health challenges. Perhaps most importantly, it has, by far, the highest quality moose habitat in Vermont due to extensive industrial timberlands. However, moose in WMU E are in the poorest health due to impacts from . It’s a cruel paradox where abundance leads to suffering.

The Density Trap

The relationship between moose density and tick infestations creates a vicious cycle that’s difficult to break. are a host density dependent parasite and thrive during times of elevated host densities. While they can be found in small numbers on other mammals, the poor grooming practices of moose mean that moose are the primary host responsible for fluctuations in tick numbers. In other words, high numbers of moose are required to support large numbers of ticks. This host-dependency explains why some areas of Vermont remain relatively tick-free while others are devastated. Most of Vermont outside of the Northeast Kingdom has never had enough moose to have enough to cause population-level impacts. It’s a matter of critical mass – once moose populations reach a certain density, they become tick factories that perpetuate their own suffering. The contrast with other regions is striking. Similarly, the 500 to 1,000 moose in New York’s Adirondack Mountains are “virtually tick-free,” says New York’s Ed Reed. “You can count the number of on an Adirondack moose on less than one hand, probably because there aren’t enough moose to get the tick cycle going.” This demonstrates that the tick crisis isn’t inevitable – it’s a function of specific ecological conditions.

Climate’s Accelerating Impact

Research has established clear connections between weather patterns and tick survival rates. Summer temperatures explained half the interannual variance in tick burden with tick burden being greater following hotter summers, presumably because warmer temperatures enhance tick reproduction and development. The evidence is overwhelming that climate change is the primary driver behind the tick explosion. Vermont’s changing climate patterns are creating ideal conditions for tick proliferation. Increasing warming trends are expected to result in an increase in white-tailed deer population and a mirrored decrease in moose population, which may have long-term impacts on Vermont’s forest composition. This creates a double threat – more hosts for parasites and fewer of the animals Vermont values most. The seasonal timing of climate impacts is particularly crucial. These effects are most significant with unusually warm spring temperatures when moose have yet to shed their winter coats. Moose are essentially trapped in their winter gear during increasingly warm springs, making them more vulnerable to heat stress and parasites simultaneously.

Fighting Back: Research and Solutions

Vermont scientists aren’t giving up without a fight. To address the growing winter tick problem the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Wildlife and Sportfish Restoration Program has supported work at the University of Vermont to research fungal spores as a possible control method for ticks. This biological warfare approach uses nature’s own weapons against the parasites. The fungal research offers hope for a sustainable solution. “These fungi are naturally occurring in the soil and have evolved to kill ticks and other insects,” said Cheryl Frank Sullivan, Research Assistant Professor at the University of Vermont’s Entomology Research Laboratory. “The fungal spores penetrate the outer shell of the tick, cause pressure on the internal tissues, and produce chemicals that help kill the pest.” However, practical application remains challenging. Further research is still needed in fungal strain development and application rate. However, using fungi that naturally occur in the environment as part of a holistic approach to pest management could prove a valuable tool as colder regions experience more impacts from a changing climate.

The Controversial Hunting Solution

Wildlife managers face a heartbreaking choice: reduce moose populations to save them. The department wants to reduce the moose population in WMU E to reduce the abundance of . This counterintuitive approach recognizes that fewer moose means fewer tick hosts, potentially breaking the cycle of infestation. The logic is sound but emotionally difficult. The argument is that reducing the moose population will also reduce the winter tick population. The moose population will be smaller but also much healthier and more sustainable going forward. It’s choosing quality over quantity in the hope of preserving Vermont’s moose heritage. Public opinion on this approach is mixed but generally supportive when the alternative is clear. “We did a public survey to understand what the residents want with the moose population in 2024,” Jones said. “People want there to be the same or more moose, but they don’t want there to be more moose if they’re unhealthy.” Vermonters want healthy moose, even if it means fewer of them.

Economic and Cultural Losses

The moose decline extends far beyond ecological concerns into Vermont’s economy and identity. While specific Vermont figures aren’t available, neighboring Maine provides insight into the economic impact. Wildlife watching contributed hundreds of millions to Maine’s economy according to available reports – the latest figure available – an increase of 82 percent since 2001, according to a report by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the U.S. Census Bureau. New Hampshire has seen its moose-watching industry virtually disappear. “Moose viewing in New Hampshire for a period of years was a $10-million-a-year industry,” he said. “But you used to be able to go out and, in a night, see a dozen or a half dozen moose at least. Now they may go several hours and see no moose.” Vermont faces similar losses as its moose populations continue declining. Culturally, moose represent something fundamental about Vermont’s wilderness character. “Moose are an iconic species in Vermont, contributing to the state’s tourist economy, local identity, and the health of our forests.” Their decline represents a diminishment of Vermont’s natural heritage that can’t be measured in dollars alone. Vermont stands at a crossroads in its battle to save its moose populations from and climate change. The statistics are sobering, the challenges immense, but the fight continues. From fungal biological controls to difficult population management decisions, scientists and wildlife managers are exploring every option to preserve these magnificent animals for future generations. The outcome of this struggle will determine whether Vermont’s children will grow up in a state where ghost moose roam the forests, or where healthy moose populations once again thrive in the Green Mountains. What do you think about it? Tell us in the comments.

Hi, I’m Andrew, and I come from India. Experienced content specialist with a passion for writing. My forte includes health and wellness, Travel, Animals, and Nature. A nature nomad, I am obsessed with mountains and love high-altitude trekking. I have been on several Himalayan treks in India including the Everest Base Camp in Nepal, a profound experience.