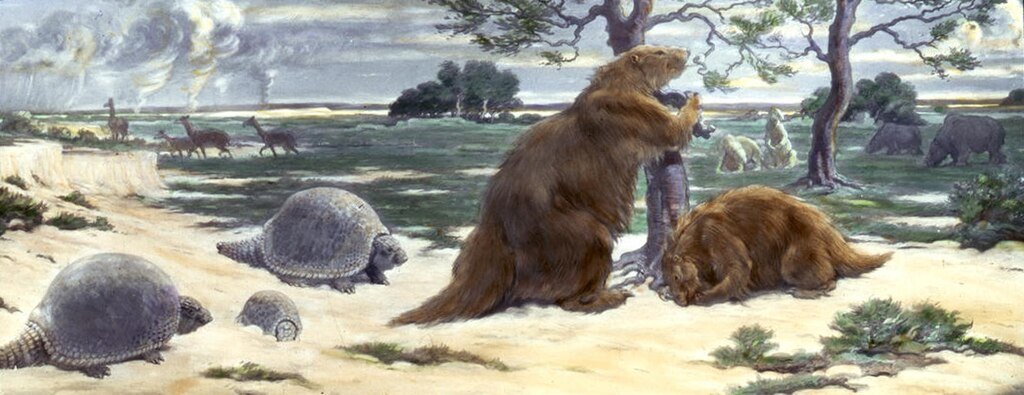

For millions of years, enormous animals roamed across prehistoric environments, some as big as elephants and others sculpting caverns with claws the size of steak knives. These were the enormous ground sloths, a strange and remarkably varied group of mammals that once ruled the Americas before apparently going extinct. Now, a revolutionary study reveals how these slow-moving titans evolved, why some grew to amazing dimensions, and where it all went wrong.

From Tiny Tree-Dwellers to Mega-Mammals

Modern sloths small, sluggish, and tree-bound are a mere shadow of their prehistoric relatives. The earliest sloths, like Pseudo Glyptodon, were modest in size, weighing no more than a large dog. But around 35 million years ago, some abandoned the trees entirely, setting the stage for an evolutionary arms race in bulk.

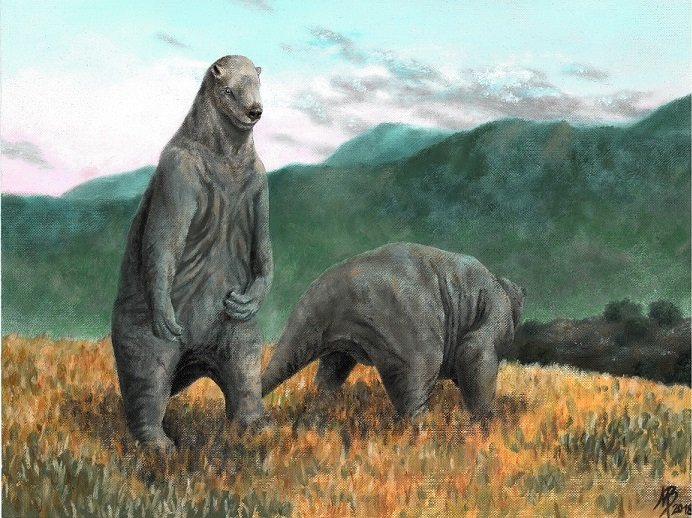

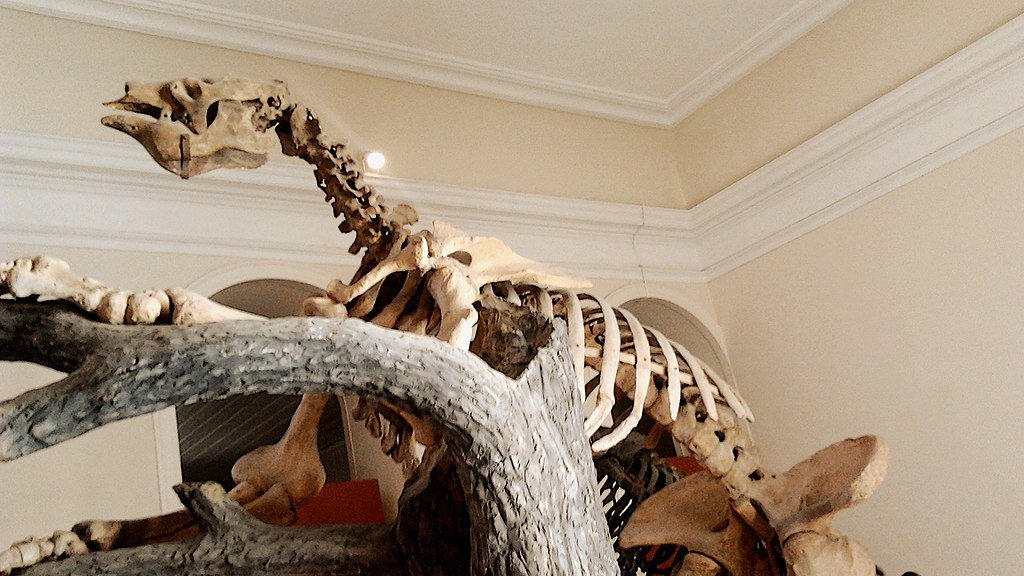

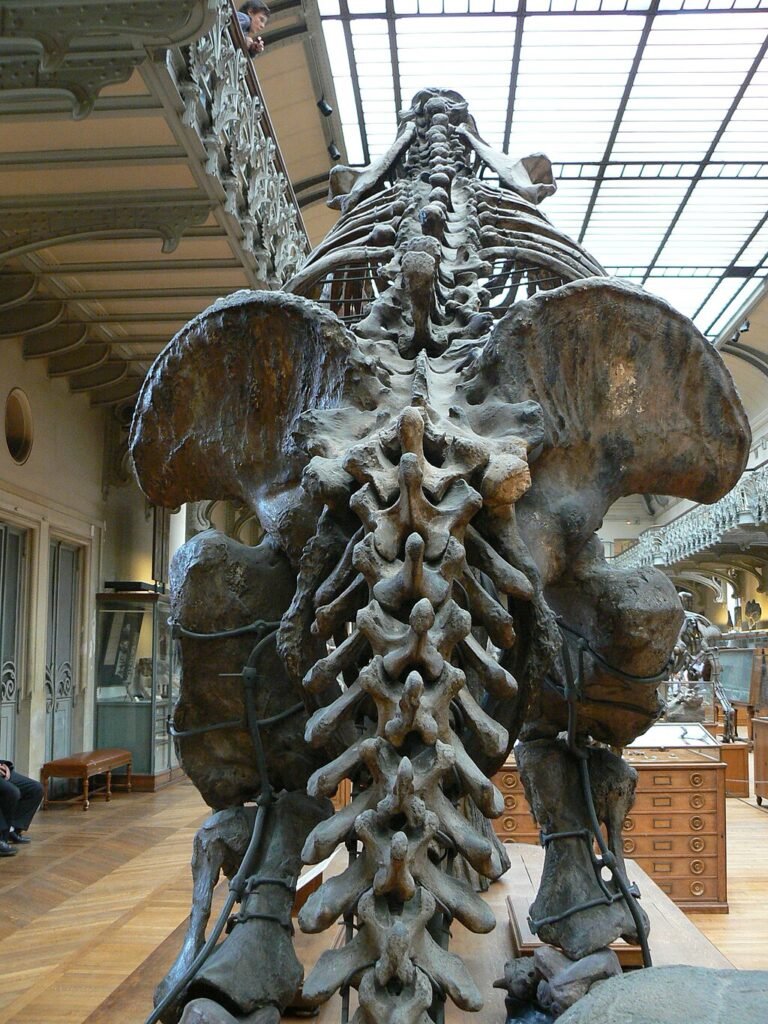

Rising to weigh up to 4,000 kg (8,800 lbs), giants like Megatherium and Eremotherium dominated the Pleistocene epoch (2.6 million to 11,700 years), surpassing any Asian bull elephant. Not all ground sloths, meanwhile, were behemoths. Relatively light at 250 kg (550 lbs), the Shasta ground sloth (Nothrotheriops) demonstrated that sloth evolution was anything from one-size-fits-all.

Why Did Some Sloths Become Giants?

In the ancient world, size was important particularly in view of predators such as dire wolves and saber-toothed cats. Bigger sloths could:

- Reach more leaves, functioning as giraffes’ ecological stand-in.

- Dig huge caverns and use their great claws to create cover.

- Withstands severe cold since, during ice ages, larger bodies better retain heat.

But larger was not always superior. While smaller sloths like Thalassocnus a marine-adapted species evolved manatee-like features including dense ribs for buoyancy and elongated snouts for grazing on seagrass, Megatherium flourished in open grasslands.

The Cave-Dwelling Poop Architects

Ground sloths had a peculiar habit: they loved caves. The Shasta ground sloth favored natural caverns in the Grand Canyon, turning them into both shelters and latrines. In 1936, paleontologists uncovered a 6-meter (20-foot) pile of fossilized sloth dung in Nevada’s Rampart Cave, a time capsule of ancient diets and ecosystems.

Bigger sloths built rather than merely occupied caves. With claws up to 30 cm (12 inches), they dug tunnels and left behind walls clearly marked with scratch marks. Silent monuments to their technical mastery, some of these caverns still exist today.

Climate Change: The Sloth Shrinker

About 15 million years ago, a cataclysmic volcanic eruption in the Pacific Northwest triggered a global warming event known as the Mid-Miocene Climatic Optimum. Sloths responded by shrinking smaller bodies helped them cope with heat stress and thrive in expanding forests.

But when temperatures plunged during the Ice Age, sloths bulked up again. Their massive size helped them conserve energy in frigid landscapes, but it also made them vulnerable to a new threat: humans.

The Mysterious Extinction: Did Humans Doom the Giants?

Around 15,000 years ago, ground sloths vanished almost entirely at a timing that suspiciously coincides with human arrival in the Americas. Unlike mammoths, which had tusks for defense, sloths were slow, heavily built, and lacked natural weapons. Early hunters likely saw them as easy prey.

Even tree sloths weren’t safe. While most ground sloths perished by the end of the Pleistocene, a few Caribbean species clung on until 4,500 years ago just long enough to witness the rise of Egyptian pyramids before disappearing.

What Their Bones Tell Us

Scientists rebuilt the sloth family tree by analyzing hundreds of fossils and ancient DNA, thus clarifying this riddle. important conclusions:

- Habitat dictated size forest sloths stayed small, while open-land giants ballooned.

- Climate shifts drove evolution, with warming periods favoring smaller bodies.

- For these slow-moving giants, human arrival probably was their last blow.

A Lost World We’ll Never See Again

There are just two small tree sloth species left today, a faint echo of a dynasty once spanning the Americas. The forests they shaped, the caverns they excavated, and the secrets they left behind remind us of a time when giants roamed the planet until, in an evolutionary blink, they were gone.

Sources:

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.