They lurk in the dark, bend time itself, and swallow light so completely that even our best telescopes see only their shadows, yet black holes have never been more visible in our imagination than they are now. In the past few years, astronomers have captured images of their silhouettes, weighed some that defy current theory, and watched others tear apart stars in violent cosmic feasts. These discoveries have pushed black holes from abstract textbook oddities into front-page news and late-night conversation. At the same time, each new observation seems to deepen the mystery: how did some of these monsters grow so big, so fast, in a universe still in its cosmic childhood? As researchers push instruments to their limits, extreme black holes are turning into natural laboratories, revealing clues about gravity, space-time, and even the ultimate fate of the cosmos.

The Hidden Clues in the Darkest Places

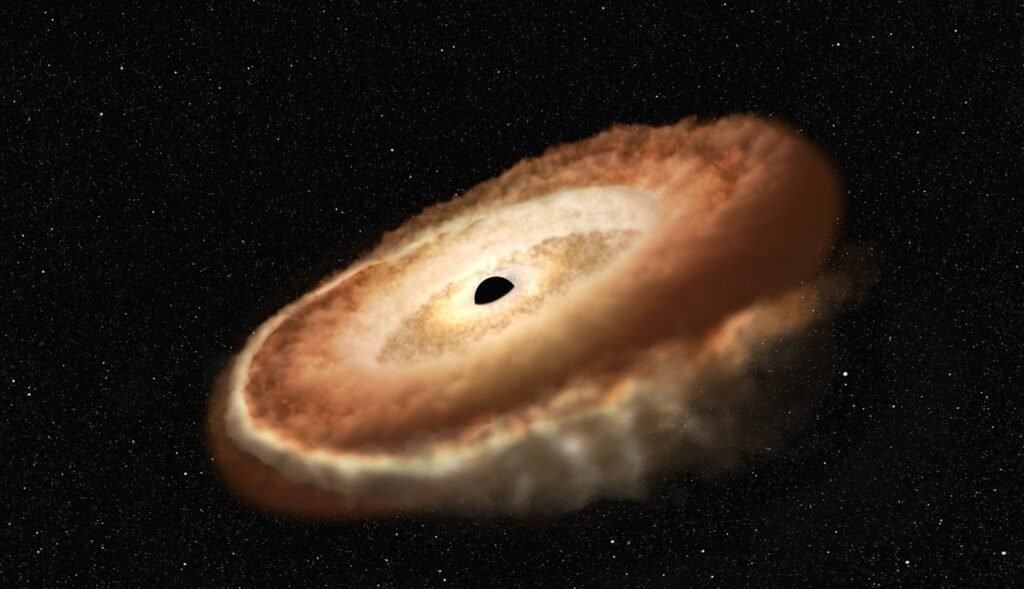

One of the strangest facts about black holes is that we never actually see them; we only glimpse what they do to everything around them. Gas spiraling in forms a blazing whirlpool called an accretion disk, heating to millions of degrees and lighting up the surrounding space in X-rays and gamma rays. In the most extreme cases, this chaos powers jets that blast matter out at nearly the speed of light, stretching for hundreds of thousands of light-years across their host galaxies. To an astronomer, these violent signatures are not just fireworks; they are fingerprints, helping to estimate a black hole’s mass, spin, and feeding habits. The darker the object, the more we have to read its surroundings like forensic scientists at a barely lit crime scene.

Some of the most powerful clues come from timing and motion rather than static snapshots. When material whirls near the event horizon, its light can flicker in subtle, almost musical patterns that encode how close it is skimming to the point of no return. Stars caught in the neighborhood trace out oddly stretched orbits, moving faster than anything in our solar system and betraying the invisible heavyweight at the center. Even the way light is lensed and distorted as it passes near a black hole gives away the geometry of space-time there. Step by step, these indirect traces allow researchers to reconstruct an object we can never touch and never see directly.

From First Theories to Monster Discoveries

For most of the twentieth century, black holes were ideas on chalkboards, not characters in a cosmic drama we could watch unfold. Early solutions to Einstein’s equations suggested that gravity could collapse matter into a region so dense that nothing could escape, but many physicists doubted anything like that could really exist. That skepticism began to fade in the 1960s and 1970s, when space-based X-ray observatories found compact, invisible objects in binary star systems that fit the profile of stellar-mass black holes. Soon after, quasar studies revealed unimaginably bright beacons in the distant universe, powered by supermassive black holes millions to billions of times the Sun’s mass. The monsters were no longer just mathematical curiosities; they were shaping galaxies.

The last decade has been a turning point, turning hints into high-resolution images and precise measurements. In 2019, the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration unveiled a now-iconic ring of light surrounding the shadow of the black hole in the galaxy M87, confirming long-standing predictions of general relativity. Follow-up images of the black hole at the center of our own Milky Way, Sagittarius A*, gave another crucial point of comparison and showed how differently a smaller, more turbulent black hole behaves. At the same time, observatories like LIGO and Virgo have been listening to the universe in gravitational waves, catching the ripples from black holes colliding in deep space. What used to be thought experiments are now daily data streams, each new detection refining what we think is possible.

Titans at the Edge of What We Understand

Some black holes are so extreme that even seasoned astrophysicists feel a twinge of disbelief when the numbers come in. At the centers of galaxies, supermassive black holes regularly tip the scales at millions of solar masses, but a growing catalog reveals giants weighing tens of billions of suns. A few candidates appear to sit uncomfortably close to the theoretical upper limits for how dense and massive such objects can be without breaking our current models of physics. Especially puzzling are supermassive black holes seen in very distant, early galaxies, which formed when the universe was only a small fraction of its current age. Somehow, in cosmic terms, they bulked up in what feels like the time it takes popcorn to go from a first few pops to a full bowl.

Extreme behavior is not only about size; it is also about what these black holes do to their surroundings. In some galaxies, the central black hole’s jets and radiation blast so much energy into the surrounding gas that they shut down star formation across tens of thousands of light-years. In others, more gentle outflows seem to stir gas just enough to help stars form, turning the black hole into an unlikely midwife of stellar birth. Astronomers now talk about feedback, a cosmic tug-of-war in which the black hole both grows by eating material and governs how much fuel its galaxy keeps. This feedback loop turns supermassive black holes into what some researchers call the thermostats of galaxies, setting the balance between growth and quiescence.

When Black Holes Collide and Space-Time Rings

Perhaps the most dramatic black hole events we can currently detect are collisions, when two of these compact objects spiral toward one another and merge. As they dance closer together, they lose energy by sending ripples through the fabric of space-time, known as gravitational waves. Detectors on Earth measure these ripples as tiny changes in the distances between mirrors, smaller than the width of a proton, triggered by cataclysmic events billions of light-years away. Each signal carries a brief, rising chirp in frequency and amplitude, encoding the masses and spins of the black holes involved. In a sense, we are listening to the universe’s most extreme mergers as if through a vast, interstellar seismograph.

The statistics emerging from hundreds of such detections are already reshaping how we think black holes form and grow. Some mergers involve surprisingly heavy stellar-mass black holes, hinting that stars in low-metal environments might collapse more efficiently than expected. Others show odd spin orientations, suggesting complicated histories in dense star clusters where black holes can pair up, break apart, and pair again. Key patterns that are beginning to stand out include:

- Many detected black holes are heavier than those inferred from X-ray binaries in our galaxy.

- A nontrivial fraction of mergers occur in the early universe, helping trace where massive stars lived and died.

- Some events hint at second-generation black holes that are the remains of past mergers.

Taken together, these signals turn the sky into a living archive of how extreme gravity has sculpted matter over cosmic time.

Peering Past the Event Horizon: What Happens Inside?

Ask any physicist what happens inside a black hole, and you will probably hear a careful mix of confidence and humility. The exterior regions, just outside the event horizon, are well described by general relativity and have now been tested by observations to impressive precision. Inside, however, our current theories run into a wall where densities and curvatures reach levels that classical physics cannot handle. Traditional models suggest a singularity, a point where known laws break down, but many researchers believe this is a sign that a deeper quantum theory of gravity is needed. For now, this inner realm remains a theoretical battleground, more like a fantasy dungeon in a role-playing game than a landscape we can actually map.

New ideas are trying to bridge that gap, exploring whether information swallowed by a black hole is somehow preserved rather than destroyed. Concepts like holographic principles, quantum entanglement, and intricate space-time geometries have all been brought into the debate. Some proposals imagine the event horizon as a fuzzy, quantum surface rather than a sharp boundary, while others toy with more radical structures that avoid singularities altogether. None of these ideas has yet won the day, but black holes are forcing physicists to confront questions about reality at its most fundamental level. In that sense, they are not just cosmic vacuum cleaners but also pressure cookers for new physics.

Why It Matters: Black Holes as Cosmic Anchors

It might be tempting to think of black holes as remote curiosities, far removed from everyday life, but they sit at the heart of crucial questions about how the universe came to look the way it does. The growth of supermassive black holes is tightly linked to the histories of their host galaxies, including our own Milky Way. When astronomers compare galaxies with and without actively feeding central black holes, they see striking differences in star formation rates, gas content, and overall structure. In rough terms, galaxies and their central black holes seem to grow up together, like partners who share both resources and scars. Understanding one helps decode the other, and together they tell the story of cosmic evolution.

There is also a quieter, philosophical importance in studying these extremes. Black holes are where our two best physical theories – general relativity and quantum mechanics – run into each other and start arguing. Traditional laboratory experiments on Earth cannot recreate the conditions near an event horizon, but observing black holes gives us a natural testbed that no particle collider can match. Insights gained here can ripple outward, influencing everything from theories of the early universe to ideas about what space and time fundamentally are. In that way, the study of black holes is less about distant monsters and more about probing the rules that govern reality everywhere, including in the most familiar corners of our own world.

The Future Landscape: New Eyes, New Wavelengths, New Questions

The next decade promises a surge of new data about extreme black holes, thanks to an armada of upcoming observatories. Space-based gravitational-wave missions aim to tune in to lower frequency signals, which are ideal for catching mergers between supermassive black holes in distant galaxies. New X-ray and gamma-ray telescopes will be able to watch accretion disks and jets with sharper vision, capturing how they flicker and flare on timescales of seconds to hours. Radio arrays are set to map the surroundings of black holes in unprecedented detail, tracing how jets thread through gas and magnetic fields. Taken together, these instruments will give us a multi-messenger, multi-wavelength view of black holes as dynamic, evolving systems rather than static objects.

With these advances come major challenges and global implications. Handling the deluge of data will require new algorithms and collaborations that cross borders and specialties, blending astronomy with computer science and statistics. As black hole measurements grow more precise, they will test general relativity under the most extreme conditions accessible, potentially revealing tiny deviations that could hint at new physics. On a broader scale, improved simulations of black hole feedback will feed into climate-like models of galaxies and galaxy clusters, helping explain the large-scale structure of the cosmos. The more clearly we see these objects, the more they become central nodes in our map of the universe, not fringe oddities.

How Curious Minds Can Join the Hunt

For a topic that sounds so remote and esoteric, black hole research is surprisingly open to curious outsiders armed with nothing more than an internet connection and a bit of patience. Space agencies and observatories regularly release imagery, animations, and even raw data, inviting the public to explore and sometimes even help classify what they see. Citizen science platforms host projects where volunteers can identify gravitational lensing features, spot unusual transients, or flag odd-looking galaxies that might host active black holes. Educational resources, from simple interactive simulations to full lecture series, let anyone follow along as new results come in. In a way, every new detection becomes a public event, not just a line in a specialist’s logbook.

There are also simple, practical ways to support the broader ecosystem that makes such discoveries possible. Following reputable science journalism, subscribing to outreach channels from observatories, and sharing accurate explanations on social media all help counter the fog of misinformation that can surround dramatic topics like black holes. Supporting science education in local schools, libraries, or community groups creates future generations of observers, engineers, and theorists who will carry this work forward. Even casual actions – like attending public talks, planetarium shows, or online live streams of major announcements – send a quiet but important signal that this research matters. In the end, black holes may be the most isolated objects in the universe, but the quest to understand them is deeply communal, powered by millions of curious minds looking up.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.