Picture this: you’re standing in a field thirteen thousand years ago, watching skilled craftspeople carefully chip away at stone with the precision of master engineers. They’re not just making tools – they’re creating technological marvels that would allow them to survive in an entirely new world. The Clovis people left behind one of archaeology’s most fascinating puzzles, and their tools tell a story of innovation that continues to amaze researchers today.

These ancient Americans were characterized as “high-technology foragers” who utilized sophisticated technology to maintain access to resources while being highly mobile. What makes their story even more remarkable is how quickly they appeared and disappeared from the archaeological record, leaving behind clues that challenge everything we thought we knew about early American ingenuity.

The Mystery of Lightning-Fast Innovation

The Clovis people existed for an astonishingly brief period, yet their technological impact was enormous. Recent analysis shows that people made and used the iconic Clovis spear-point and other distinctive tools for only 300 years, from 13,050 to 12,750 years ago.

This narrow timeframe raises fascinating questions about innovation under pressure. Researchers still don’t know how or why Clovis technology emerged and why it disappeared so quickly. Think about it – in just three centuries, they developed, perfected, and then abandoned one of the most sophisticated weapon systems of the ancient world.

It’s intriguing that Clovis people first appeared 300 years before the demise of the last megafauna that once roamed North America during a time of great climatic and environmental change. Their technological prowess may have been both their survival tool and, ironically, a contributor to the end of an entire ecosystem.

The Revolutionary Fluted Point Design

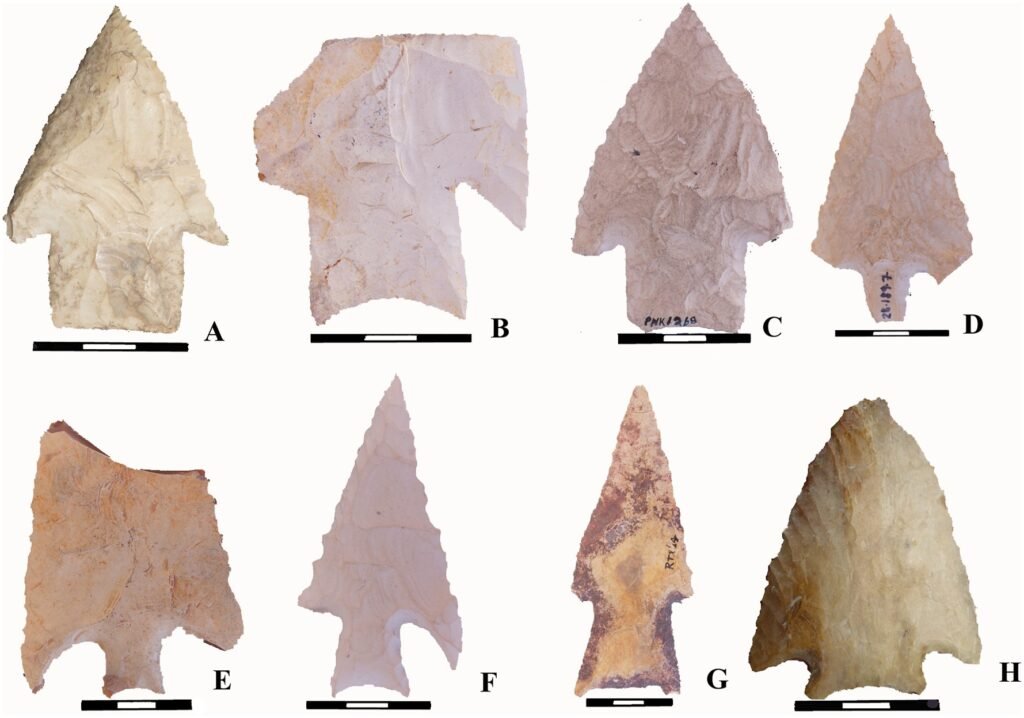

The channels, or “flutes,” near the base of projectile points are the hallmark of the Clovis industry, created by removing broad flakes from either side of the point to aid in hafting the point to a spear shaft. This might sound like a minor detail, but it was revolutionary engineering.

A typical Clovis point is a medium to large lanceolate point with sharp edges, one to two inches wide, about four inches long, with sides that are parallel to convex and exhibit careful pressure flaking along the blade edge. The broadest area towards the base features those distinctive concave grooves called flutes.

This seemingly minor aspect of Clovis projectile point technology is considered by anthropologists to have been a crucial key to the success of Clovis people, allowing them to sweep across North America and down through the tip of South America at a remarkably swift rate. The fluting wasn’t just decorative – it was a game-changing innovation that made their weapons incredibly reliable.

Successfully fluted Clovis points would have been extremely reliable, especially while traveling great distances into unknown regions on a new continent, as they needed points that would hold up and be used over and over again, with the fluted-point base acting as a “shock absorber,” increasing point robustness and ability to withstand physical stress.

The Engineering Challenge of Fluting

Creating a fluted point wasn’t easy – it was one of the riskiest manufacturing techniques in the stone tool world. Archaeological evidence suggests that up to one out of five points break when trying to chip this fluted base, and it takes at least 30 minutes to produce a finished specimen. Imagine the skill required when a single mistake could destroy hours of careful work.

Fluting is a tricky process because it’s easy to break a biface by delivering a forceful blow at the biface’s end, and if the striking platform is not positioned precisely, the resulting flake can be too shallow or the flake can dive through the biface removing the distal end.

The act of fluting requires incredible skill, and many fluted points appear to have been fractured during the manufacturing process, with broken, partially fluted tools being well documented in the archaeological record. Yet despite this challenge, Clovis knappers mastered the technique across the continent.

The flint knapping technique of “fluting” the Clovis points could be considered the first truly American invention, as this singular technological attribute, the flake removal or “flute,” is absent from the stone-tool repertoire of Pleistocene Northeast Asia, where the Clovis ancestors came from.

The Science of Stone Tool Manufacturing

The Clovis toolkit went far beyond their famous points. The Clovis toolkit includes fluted points, bifaces, side scrapers, end scrapers, retouched blades and flakes, perforators, and cobble tools. Each tool represented specialized engineering for specific tasks in their mobile lifestyle.

It appears that Clovis points often started out mostly percussion flaked, and through use and reshaping, they came to have more extensive pressure flaking across their surfaces, with Clovis knappers taking care to preserve the flute scars and not pressure flake across them if they could help it.

The lower edges of the blade and base are ground to dull edges for hafting, with the final step being heavy grinding to margins of the base, which was done to all finished points as a good indicator that the maker considered the point to be finished. This attention to detail shows they understood both the mechanical and safety aspects of their weapons.

Bone and Ivory: The Forgotten Technologies

While stone points grab the headlines, Clovis bone technology was equally sophisticated. Other stone tools used by the Clovis culture include knives, scrapers, and bifacial tools, with bone tools including beveled rods and shaft wrenches, with these rods made of bone, antlers, and ivory.

The function of the rods is unknown and has been subject to numerous hypotheses, with rods that were beveled on both ends most often interpreted as foreshafts to which stone points were hafted. Think of these as the sophisticated mounting systems for their precision weapons.

Experimental replication and mechanical testing led to the conclusion that the rods from sites served a primary function as levered hafting wedges used to tighten sinew binding on saw-like implements. These weren’t crude tools – they were engineered components of complex weapon systems.

Researchers have proposed that the double beveled bone rods may have been foreshafts for spears, with Clovis points hafted onto one of the bevels and the other lashed to a wooden main shaft. This represents sophisticated multi-component engineering that rivals modern weapon design principles.

The Cache System: Ancient Storage Technology

One of the most intriguing aspects of Clovis technology is their caching behavior. Over thirty Clovis caches have been identified across North America, where artifacts were often found grouped together in caches where they had been stored for later retrieval.

A distinctive feature of the Clovis culture generally not found in subsequent cultures is “caching,” where a collection of artifacts were deliberately left at a location, presumably with the intention to return to collect them later, with over thirty such caches identified across North America.

Clovis caching behavior is interpreted as a strategy for maximizing exploration and migration rather than an embedded strategy associated with an annual foraging round, suggesting that the Clovis technocomplex may have originated along the North Pacific coast before rapidly spreading across the continent. This wasn’t random storage – it was strategic resource management on a continental scale.

Quality Control: Precision in Every Detail

The consistency of Clovis technology across vast distances reveals something remarkable about their quality standards. The similarity of Clovis tools from site to site demonstrates the great adaptability of the tools to all the environments of the Americas at the end of the last ice age.

When compared to modern Clovis point replicas made by an expert knapper, the flake scar contours of the ancient Clovis points showed little morphological variation and a large degree of bifacial symmetry, supporting the existence of a widespread standardized “Clovis” knapping technique.

In many Clovis localities, the stone tools found at a site were hundreds of kilometers away from the source. This suggests not only extensive trade networks but also quality control standards that ensured tools would perform reliably regardless of where they were made or used.

The Legacy of Ancient Innovation

Most researchers believe that the rapid dissemination of Clovis points is evidence that a single way of life swept across the continent in a flash, with no other culture dominating so much of the Americas. Their technological influence was unprecedented in scope and speed.

Clovis points were made for three or four centuries, then disappeared along with the culture that created them, as Clovis people settled into different ecological zones and the culture split into separate groups, marking the beginning of the enormous social, cultural and linguistic diversity that characterized the next 10,000 years.

The Clovis people’s tools reveal minds capable of extraordinary innovation under pressure. They developed sophisticated engineering solutions, implemented quality control across vast distances, and created storage systems that supported continental exploration. Their brief but brilliant technological legacy reminds us that human ingenuity has always found ways to adapt and thrive, even in the face of an unknown and changing world.

The tools left behind by the Clovis people represent more than ancient artifacts – they’re testament to human creativity, precision engineering, and the drive to innovate when survival depends on it. What strikes me most is how they managed to standardize such complex technology across an entire continent in just three centuries. What would you have done if you’d been tasked with perfecting a weapon system for exploring a completely new world?

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.