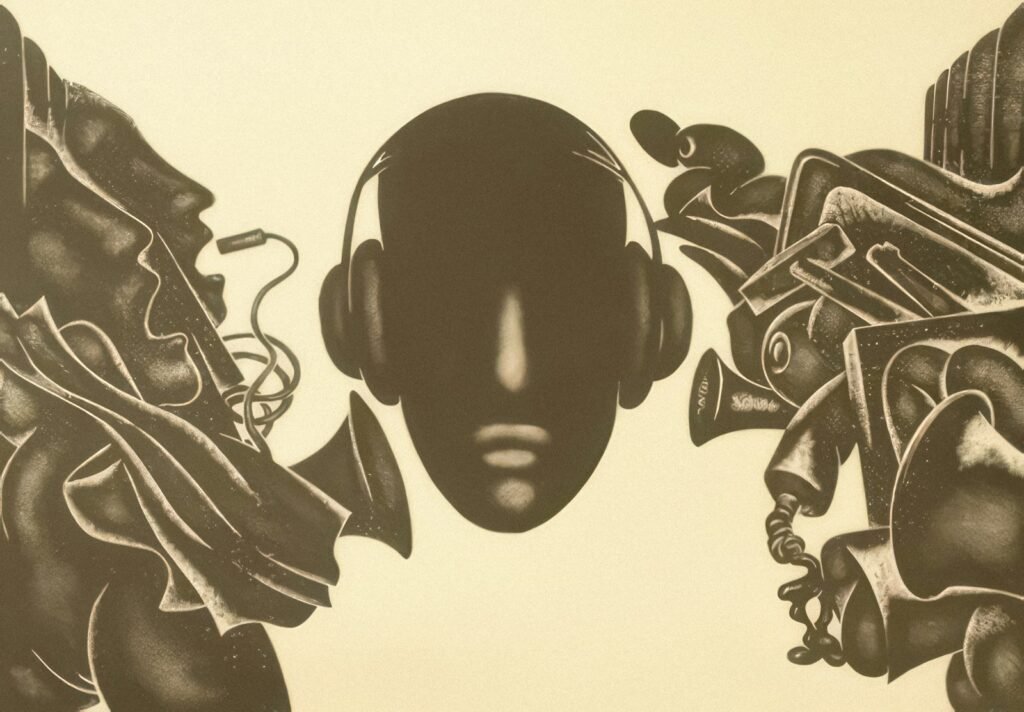

Walk into any gym, wedding, or late-night diner and you can feel it before you think it: music quietly taking the wheel of your brain. A song you have not heard in years can yank you back to a teenage bedroom, a hospital waiting room, or a first kiss with unnerving precision. For decades, scientists knew music mattered but lacked the tools to see how deeply it rewires mood, memory, and even our sense of self. Now, with brain scanners, big data, and clever experiments, researchers are mapping how sound carves pathways through the nervous system. What they are finding is turning a familiar, everyday experience into one of the most revealing windows into the human brain.

The Hidden Clues in a Single Song

Think about the last time a random song sent a chill down your spine; that tiny shiver is your nervous system giving away its secrets. Researchers have found that these so-called “frisson” moments often line up with musical surprises: a sudden key change, a swelling choir, or a drop in the beat that breaks your expectations. In brain scans, these shocks of pleasure show up as bursts of activity in reward circuits like the nucleus accumbens and ventral striatum, the same areas that respond to food, social praise, or addictive drugs. At the same time, the auditory cortex is working overtime, predicting what should come next and flagging the moments when the music cleverly breaks the rules. In other words, your brain is not a passive listener; it is constantly gambling on what the next note will be – and paying out in dopamine when it guesses right or is surprised.

Those hidden reactions explain why two people can hear the same song and have completely different emotional experiences. If your brain has been trained on years of jazz, a complex chord change feels pleasingly logical; if you grew up on simple pop melodies, the same passage might feel confusing or even irritating. Studies suggest that roughly about one third of people report experiencing intense chills to music, but the patterns depend on their personality, musical exposure, and even how willing they are to let go and feel vulnerable. Tiny details – like a breath between phrases or the crack in a singer’s voice – act like emotional highlighters, amplifying the story your brain is already telling itself. The clues were always there in the sound; we are just finally learning to read them.

From Ancient Rhythms to Modern Brain Scanners

Long before anyone knew what a neuron was, humans were using rhythm and melody as tools: to coordinate hunting, soothe infants, and mark rituals from birth to burial. Archaeologists have uncovered flutes carved from bird bone and mammoth ivory that are tens of thousands of years old, suggesting that music is not some cultural afterthought but one of our earliest technologies. Anthropologists studying traditional societies today still see music woven tightly into communal labor, healing ceremonies, and storytelling. All of this hints that our brains evolved in a world where sound was not background noise but a core part of social survival. When we drum our fingers or hum absentmindedly, we are echoing habits that helped knit early human groups together.

Modern neuroscience is now catching up to that long history with hard data. Functional MRI and EEG studies show that listening to music is not a localized event; it lights up a distributed network including motor regions, emotion centers like the amygdala, memory hubs in the hippocampus, and even areas involved in theory of mind. That broad activation pattern is one reason music can reach people whose language abilities are damaged by stroke or dementia. Compared with language alone, rhythm and melody seem to have a more direct line into subcortical circuits that evolved long before speech. Ancient drum circles and today’s playlists may look worlds apart, but under the skull, the same old circuitry is pulsing along.

How Sound Hijacks Mood in Minutes

Anyone who has rage-quit a stressful commute playlist or leaned on sad songs after a breakup knows that music can swing mood with unnerving speed. Laboratory experiments back this up: within just a few minutes of listening, people’s reported emotions, heart rate, breathing patterns, and even skin conductance shift in measurable ways. Upbeat, high-tempo tracks tend to increase arousal, nudging the sympathetic nervous system into a more activated state, whereas slow, gentle pieces can enhance parasympathetic activity and promote relaxation. Hormone studies have shown that calming music can reduce cortisol, a key stress hormone, while certain rewarding pieces can bump up oxytocin, often linked with bonding and trust. This makes music not just a background aesthetic but an honest-to-goodness lever for our internal chemistry.

That chemical leverage can be powerful enough to alter clinical outcomes. In hospitals, patients who listen to carefully chosen music before surgery often report lower anxiety and sometimes need slightly less sedative medication. In mental health settings, music therapy is being used alongside traditional treatments to ease symptoms of depression, post-traumatic stress, and chronic pain. Some meta-analyses suggest that for mild to moderate anxiety, structured music interventions can have an impact comparable to common psychological strategies, at least over the short term. Of course, blasting your favorite track is not a miracle cure, and it can backfire if the song is tied to painful memories. But for many people, music becomes a flexible, low-cost mood regulator hiding in plain sight.

Why Music Hooks So Deep into Memory

It is almost eerie how a tune you have not heard since childhood can snap back into place with every lyric intact, while you struggle to remember what you had for lunch two days ago. That contrast exists because music and memory share overlapping brain circuits that are especially well suited to long-term storage. The hippocampus, a key region for forming new memories, works hand in hand with auditory areas and the prefrontal cortex to encode not just the melody, but also the context: who you were with, what you were feeling, what the room smelled like. Rhythm and repetition act like scaffolding, making it easier for the brain to compress and retrieve those experiences later. Researchers suspect this is why people with Alzheimer’s disease can sometimes still sing along to songs from their youth even when they no longer recognize family members.

Small but striking clinical studies have used this quirk of the brain to spark dormant memories. When caregivers play familiar songs from a patient’s teens and early adulthood, they often see brief windows of clarity – eyes light up, lips form words, and old stories come tumbling out. In stroke rehabilitation, singing phrases can sometimes help patients regain spoken language, a technique known as melodic intonation therapy. On a more everyday level, students have long exploited music’s mnemonic power, pairing facts with rhythms to remember formulas or vocabulary. It is as if melody provides a sturdy suitcase and our fragile memories hitch a ride inside. When that song comes back years later, the suitcase pops open and the past spills out.

Why It Matters: Music as a Window into the Brain

It is tempting to treat music as a pleasant extra in human life, the auditory equivalent of frosting on a cake, but that vastly underestimates its scientific importance. Music forces the brain to integrate prediction, emotion, memory, and movement in real time, making it one of the best natural stress tests of our neural networks. Compared with many traditional psychological tasks – pressing a button to indicate a color, or reading a list of words – music is richer, messier, and far closer to the complexity of real life. When researchers map how brains respond to melodies, they are not just studying art; they are charting how flexible, predictive, and socially tuned our minds really are. That is why music research is increasingly showing up in conferences that used to focus on language and vision alone.

This shift also challenges older models of the brain that kept functions neatly separated. For years, textbooks presented music as if it lived in a narrow strip of the right hemisphere, a kind of decorative sidebar to serious cognitive work. Newer studies show the opposite: musical engagement recruits bilateral networks and can enhance abilities from attention control to auditory discrimination. The fact that choir practice or drumming circles can shift white matter connections and strengthen timing skills forces scientists to rethink how plastic the adult brain really is. In a way, music is exposing the brain’s bias toward rhythm, pattern, and social connection – a bias that underlies language, movement, and even cooperation. Ignoring music would mean ignoring one of the clearest, most accessible demonstrations of how dynamic our nervous systems can be.

Global Perspectives: Different Cultures, Shared Circuits

Even though playlists in Seoul, Lagos, and Nashville sound wildly different, the brains listening to them share some strikingly similar responses. Cross-cultural experiments have found that people with no exposure to Western music can still distinguish happy from sad pieces based on tempo and mode, suggesting some emotional cues are at least partly universal. At the same time, cultural learning shapes what counts as pleasant or dissonant, and what patterns feel satisfying. For example, scales that sound perfectly natural in one tradition can feel tense or unresolved to listeners raised on another. These differences let scientists tease apart what is hardwired in our auditory system from what is learned through years of immersion.

Global research also reveals how communities harness music for collective regulation of mood and identity. Protest movements chant and sing not just to send a message, but to synchronize hearts and breathing, building a kind of physiological solidarity. Religious services on every continent use drums, bells, or chanting to guide attention and induce states that participants describe as transcendent or deeply calming. In many cultures, lullabies are passed down almost unchanged for generations, acting as soft, portable tools for emotional regulation in babies and caregivers alike. My own grandmother hummed the same simple melody her mother used, and decades later, I still feel my shoulders drop when I hear it by accident in a film or shop. Beneath all the cultural variety, our brains keep using music as a shared emotional language.

The Future Landscape: AI Playlists, Neurotech, and Ethical Questions

As streaming platforms gather data on billions of listening hours, music is quietly becoming a large-scale experiment on human emotion. Algorithms are learning which progressions help people focus at work, which rhythms keep them on a treadmill longer, and which late-night tracks mean someone might be spiraling into sadness. Some companies are already marketing adaptive playlists that shift in response to your heart rate, facial expressions, or typing speed. At the same time, researchers are testing closed-loop systems where brain signals feed directly into generative music engines, creating soundscapes tailored to calm an anxious mind or keep a driver alert. The line between simply choosing songs and having our nervous systems steered by them is growing thinner every year.

These tools open exciting possibilities but also thorny ethical problems. If music can reliably nudge mood and behavior, who controls that lever when you are shopping, voting, or scrolling social media? There is serious talk of using personalized soundtracks to manage chronic pain or insomnia, which could reduce drug dependence for some patients. But there is also a risk of overreliance, or of subtle manipulation in contexts where consent is murky, such as workplaces or public spaces. On a global scale, wealthy health systems may gain access to brain-responsive music therapies long before lower-income communities do, widening existing inequalities. The future of our brains on music will depend not just on clever engineering, but on whether we are willing to set guardrails around how, where, and why those sonic tools are used.

How to Listen Differently: A Quiet Call to Action

You do not have to wire yourself to a brain scanner to start using music more deliberately; you just have to pay closer attention. One simple step is to keep a “mood map” of your listening for a week, jotting down how different songs affect your focus, anxiety, or sense of connection. You will probably spot patterns: tracks that reliably wind you up before bed, or old albums that leave you strangely calm on tough days. With that knowledge, you can build small, science-informed rituals – an energizing playlist for tedious chores, a calming set of instrumentals for commuting, or familiar songs to help an older relative reconnect with long-buried memories. You are essentially running your own tiny, personalized experiment in emotional neuroscience.

Beyond your headphones, there are ways to nudge the wider world toward healthier, more thoughtful use of sound. Supporting local music programs, especially in schools and community centers, helps give more brains access to one of the most potent plasticity tools we know. If you have a loved one dealing with dementia, stroke, or chronic stress, you can ask their clinicians about evidence-based music interventions rather than assuming it is “just entertainment.” And when you encounter new technologies promising to hack your brain with proprietary frequencies, it is worth bringing a dose of skepticism and asking what evidence actually exists. Our brains on music are more malleable, more vulnerable, and more extraordinary than we once believed – and that makes how we listen, and what we fund, more important than ever.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.