A new study has shed light on the rare and enigmatic practice of bed burials in early medieval Europe, revealing a complex and regionally diverse funerary tradition. Published in the European Journal of Archaeology, the research by Dr. Astrid Noterman explores over 60 known bed burials from the sixth to tenth centuries AD, spanning Germany, England, and Scandinavia. These burials, where the deceased were interred on wooden beds, challenge assumptions about uniformity in early medieval rites and offer fresh insights into gender, status, and cultural exchange.

What Are The Bed Burials and Where Were They Found

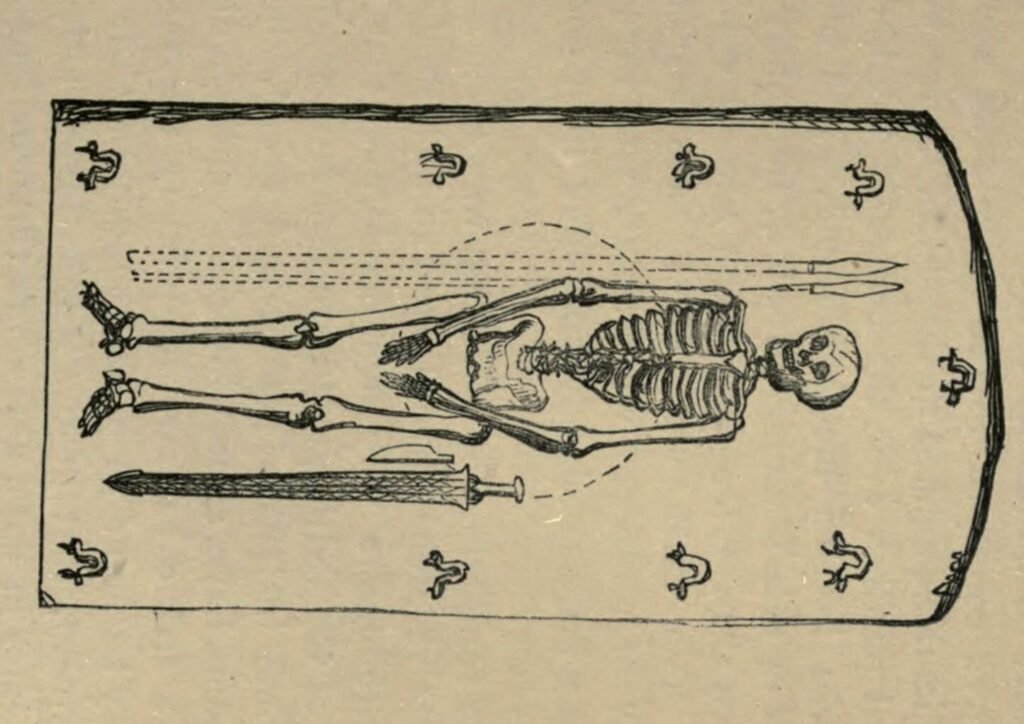

Bed burials involve placing the deceased on a wooden bed within a grave, often accompanied by personal items or grave goods. Though rare, they have been discovered in various contexts—from isolated mounds to formal cemeteries. In Germany, they are typically found in unmarked cemeteries and include both men and women, often with modest grave goods such as bowls or rings. In contrast, English examples frequently involved dismantled beds and are predominantly female, sometimes associated with Christian symbols like crosses. Scandinavian bed burials, such as those at Oseberg and Gokstad, are more monumental and often linked to elite ship burials, suggesting a different symbolic framework.

Gender, Age, and Social Identity in Bed Burials

The study reveals that bed burials dominate in England. In Germany and Scandinavia, both sexes and various age groups were represented. Notably, sub-adult burials differ by region: German examples often include children aged three to seven, while English ones typically involve adolescents aged thirteen to eighteen. Grave goods also vary, with female burials frequently including weaving tools, possibly reflecting gendered roles or symbolic associations associationswith domestic and transformation.

Cultural Transmission and Christian Influence

One of the most intriguing findings is the suggestion that bed burial practices may have been introduced to England through the movement of women during Christianization. Isotopic analysis of some English burials indicates that the women were not native to Britain, supporting the idea of cultural transmission via migration. In England, the practice took on a distinctly Christian and feminine character, diverging from its more varied continental counterparts. This highlights how burial customs can be reshaped by local beliefs, religious shifts, and social dynamics.

Rethinking Bed Burials as a Unified Tradition

Rather than representing a single, coherent ritual, bed burials appear to be a constellation of related practices with shared elements but distinct regional expressions. Dr. Noterman argues that the diversity in burial settings, grave goods, and the biological profiles of the deceased suggests multiple meanings and functions. Some may have marked transitional identities, elite status, or spiritual roles, while others reflected local customs or familial memory. This pluralistic view challenges earlier interpretations that sought a singular explanation for the phenomenon.

Conclusion

The rediscovery and reanalysis of medieval bed burials offer a compelling glimpse into the social and spiritual landscapes of early medieval Europe. Far from being a uniform rite, these burials reflect a tapestry of identities, beliefs, and cultural exchanges. As archaeologists continue to uncover and reinterpret these graves, they not only illuminate the lives of the individuals buried in them but also the evolving values of the communities that laid them to rest.

Source:

European Journal of Archaeology