Long before observatories, satellites, or even telescopes, people around the world could look up at a darkening sun or a blazing comet and calmly say, in effect, “We knew this was coming.” For many Indigenous cultures, eclipses and comets were not random terrors but expected visitors, woven into careful cycles of observation and story. Today, astronomers can compute such events centuries in advance, yet we are only beginning to understand how deeply traditional knowledge systems anticipated the same patterns. As debates about whose science counts grow louder, these sky traditions are quietly rewriting the history of astronomy. What happens when we finally treat Indigenous star knowledge not as myth, but as data?

The Hidden Clues in a Darkening Sky

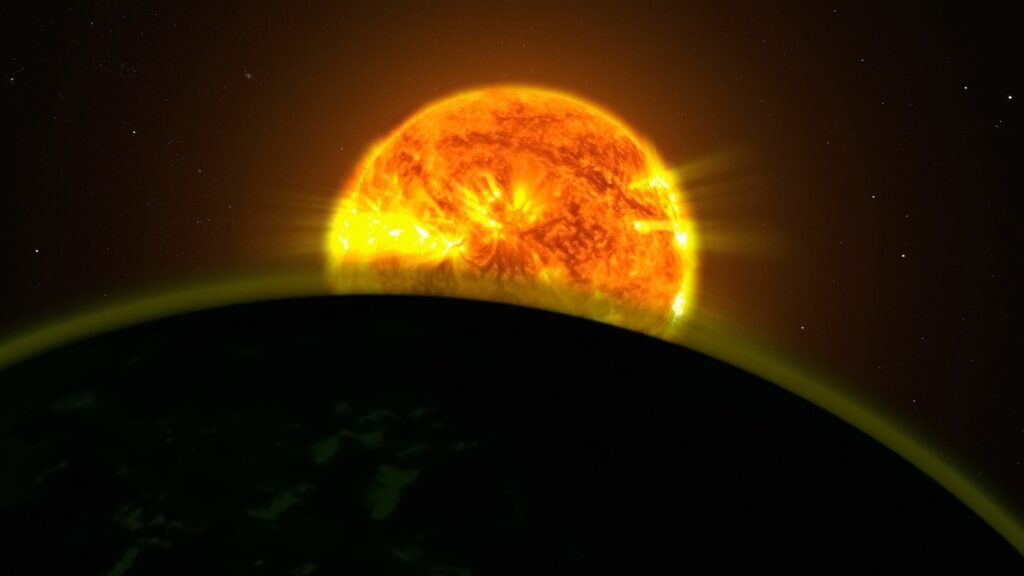

Imagine standing in a clearing as the daylight thins, birds fall silent, and shadows sharpen – an eclipse coming on with unnerving speed. For many Indigenous communities, this was not a chaotic surprise but a rehearsed chapter in a much longer story about the sky. By watching the moon’s motion night after night, elders could see subtle clues: the way it crept toward the sun’s path, the timing of new moons, the return of familiar alignments. Over generations, these signs became patterns, and patterns became rules, passed down in ceremony, narrative, and practice.

Instead of written equations, these cultures encoded eclipse cycles in ways people would remember: dramatic tales of a cosmic creature swallowing the sun, or rituals performed only when the moon met specific conditions. Those stories may sound like pure metaphor from a distance, but they often functioned as precise memory devices, ensuring that people knew when to expect the next sky-darkening event. In some regions, the predicted timing of eclipses was closely tied to agricultural calendars and large communal gatherings, so getting it wrong was not an option. What seems like myth from the outside often turns out to be meticulous observational science hiding in plain sight.

Watching the Sky Like a Library

One of the biggest misconceptions about ancient and Indigenous astronomy is that it was casual – people simply glanced up now and then and drew wild conclusions. In reality, the sky was treated like a living library, and many communities maintained careful, intergenerational “reading” practices. In traditional Native American, Māori, Aboriginal Australian, and Andean societies, trained knowledge keepers tracked the behavior of the sun, moon, and planets over many lifetimes. Each rising point on the horizon, each unusual halo, each early star at dusk was a note in a much larger dataset.

Comets posed a special challenge because they do not follow the neat, easily memorized schedules of lunar eclipses. Yet they, too, were folded into this library of experience. When a comet blazed across the sky, elders compared it to past sightings: its brightness, direction, and timing relative to seasonal markers. Some cultures came to recognize that certain long-period comets returned over many generations, building a kind of slow-motion memory that spanned far beyond any one human life. Committees of astronomers today call that long-baseline data; Indigenous communities did it with stories, ritual remembrance, and relentless sky-watching.

From Story to Cycle: The Science Inside the Myths

Modern astronomers talk about the Saros cycle, a roughly eighteen-year pattern that links eclipses in a repeating rhythm. Many Indigenous traditions, without that label or the underlying geometry, still noticed that eclipses came in families – if an eclipse happened around the time a grandparent remembered, another might arrive when their grandchildren were grown. Instead of tables, they used genealogies, marking time by births, deaths, and landmark events that coincided with eclipses or comets. The result was a human-centered timing system that nevertheless mapped onto very real celestial cycles.

When anthropologists and astronomers began comparing oral traditions with historical eclipse records and orbital models, some of these correspondences turned out to be startlingly accurate. Stories that anchored a great battle or migration to a sky-darkening event often lined up with known total eclipses visible in that region. Tales of a “hairy star” appearing before a famine or leadership change sometimes matched known comet returns. This does not mean every legend is a literal logbook, but it undercuts the lazy idea that such accounts are pure fantasy. Under the surface imagery, there is often a sharp observational core.

Earth, Stones, and Shadows as Observatories

While we tend to picture astronomy as something done with lenses and electronics, many Indigenous cultures turned the land itself into a measuring device. In the American Southwest, for example, rock carvings, spiral petroglyphs, and strategically placed structures appear to interact with sunlight and shadow on key dates. On certain mornings, the rising sun sends a narrow beam of light that slices across a specific symbol only during solstices or equinoxes. Over years, these same alignments can be used to anticipate when the sun and moon might overlap more closely in the sky, hinting at an eclipse season.

Similar sky–land observatories appear in Indigenous-built alignments worldwide, from standing stones in Oceania to horizon markers in the high Andes. These are not random monuments; they act like fixed points in a giant celestial protractor, letting observers notice when paths and angles deviate from the norm. If the sun is rising slightly off its usual notch, or the moon is cutting across an unexpected part of the sky, something out of the ordinary could be approaching. It is a slower, more patient way of doing what modern eclipse prediction software does in seconds – measuring, comparing, and recognizing when a rare alignment is on its way.

Global Perspectives: Diverse Skies, Shared Methods

Across continents, Indigenous sky traditions developed independently but often arrived at similar strategies for predicting rare events. Polynesian navigators, for instance, tracked star positions and lunar phases so precisely that they could detect subtle anomalies in the night sky, folding that knowledge into wayfinding and seasonal decision-making. In parts of Africa, star risings and moon–sun relationships formed the backbone of agricultural calendars and ritual cycles, some of which signaled periods when eclipses were more likely. In the Arctic, Inuit observers integrated the behavior of the moon and sun with changes in ice, animal migrations, and light phenomena, building a holistic model of environmental timing.

What unites these apparently different cultures is not a shared mythology but a shared method: long-term, communal observation combined with conservative memory-keeping. Key facts were repeated in song, retold at ceremonies, and attached to practical knowledge like planting or fishing. Over time, this created a high-resolution record of the sky, even in places with no written language. It is a reminder that data does not have to live in spreadsheets to be rigorous. The sky is global, and so is the human capacity to notice its smallest quirks.

Why It Matters: Rethinking Who Owns “Real” Astronomy

In mainstream accounts of science history, astronomy usually begins in Mesopotamia, Greece, or Renaissance Europe, then jumps straight to modern observatories. Indigenous knowledge often appears, if at all, as a colorful sidebar. That narrative sends a quiet but harmful message about whose observations are considered legitimate. When researchers show that an Indigenous tradition correctly describes an eclipse thousands of years ago, or encodes an accurate understanding of lunar motion, it forces a rethinking of that storyline. The implication is not that modern astronomy is wrong, but that its family tree is much broader than it likes to admit.

This matters for more than historical fairness. As climate change, light pollution, and satellite swarms reshape the sky, communities that have maintained close relationships with celestial patterns can offer crucial context. Their records, preserved in story and ceremony, sometimes extend further back than written local archives. By comparing these narratives with physical evidence and modern models, scientists can reconstruct past environmental conditions and sky visibility in ways no instrument alone can match. Acknowledging Indigenous astronomy as science also opens doors for younger Indigenous researchers, who can move between ancestral knowledge and cutting-edge astrophysics without having to choose one over the other.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science Collaborations

In the past few decades, a growing number of astronomers and Indigenous knowledge holders have begun working together, rather than talking past each other. Projects in North America, Australia, and the Pacific bring elders and astrophysicists into the same field sites, comparing traditional sky stories with star charts, eclipse catalogs, and orbital data. When a particular tale mentions a darkened sun during harvest or a fiery visitor in a specific season, researchers can now check whether a known eclipse or comet aligns with those details. Sometimes the fit is surprisingly close, prompting new respect for observational precision in oral traditions.

These collaborations are changing how observatories are built and operated. In some regions, major telescopes now consult with local Indigenous communities about sacred sky directions, culturally important asterisms, and appropriate naming practices. Instead of treating ancient skywatchers as people who “almost” did science, astronomers are beginning to see them as early colleagues whose records fill in gaps. It is still an uneven process, and power imbalances have not vanished, but the trend is clear: the old divide between “myth” and “science” is being replaced, slowly, by a spectrum of sky knowledge that runs seamlessly from stone circles to space telescopes.

The Future Landscape: AI, Satellites, and the Fight for a Dark Sky

Looking ahead, predicting eclipses and comets is the easy part; computers already solve those equations for centuries in either direction. The real challenge is protecting a sky that future generations can still read, whether through software or story. Light from cities is washing out the faintest stars, while satellites create moving scars that cut across long-exposure images and even cultural ceremonies tied to pristine night skies. Indigenous communities that have long relied on clear celestial markers are among the first to notice these disruptions, treating them as environmental changes, not just aesthetic annoyances.

At the same time, emerging tools like artificial intelligence and all-sky monitoring networks could become unlikely allies. Automated systems can track every bright object that appears, flagging unexpected comets or transient events faster than ever. Imagine pairing that digital vigilance with Indigenous skykeepers who understand not just what is happening, but what it means in the context of place, season, and long memory. Some researchers are already exploring ways to encode traditional star patterns into software and educational apps, so that future eclipse predictions come with a parallel view of how that event has been understood locally for centuries. The future of astronomy may be high-tech, but its roots will be stronger if they stay anchored in the oldest relationships humans have with the sky.

How You Can Engage: Listening, Protecting, Supporting

For most of us, the night sky has become a background, something we notice only during a big headline eclipse or a rare blazing comet. Reclaiming even a fraction of the attention our ancestors gave it can be surprisingly powerful. One simple step is to seek out Indigenous-led programs, talks, or planetarium shows that share local sky knowledge, especially in the region where you live. Listening to how the same eclipse on your calendar fits into a much older cycle of stories and observations can change the way you experience that event. It shifts you from being a passive spectator to a participant in a very long experiment.

You can also support efforts to protect dark skies and respect Indigenous perspectives in astronomy projects. That might mean backing local ordinances that reduce light pollution, following organizations that advocate for responsible satellite deployment, or supporting community-led initiatives that document and revitalize traditional star knowledge. The next time a predicted eclipse makes headlines, remember that this is not a purely modern achievement; it is the latest chapter in a story humans have been refining for thousands of years. And when you step outside to watch the shadow move or the comet flare, you might ask yourself whose footsteps you are quietly following.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.