It began as a miracle in bone: a long, straight horn, a hulking spine, and the promise that myth could be real. In early modern Europe, collectors craved wonders, and the so-called Magdeburg Unicorn delivered a spectacle – part science, part stagecraft. But the fossil fairy tale unraveled as researchers learned to read the deep past with sharper eyes and steadier methods. What looked like a unicorn proved to be something far more interesting: a jigsaw of Ice Age giants, misread through the lens of legend. That twist isn’t a letdown; it’s the real adventure of how science corrects its own stories.

The Hidden Clues

The Hidden Clues (image credits: wikimedia)

What if the most famous unicorn never belonged to a single animal at all? The Magdeburg figure, assembled in the seventeenth century, wasn’t a skeleton discovered intact but a dramatic mash-up of fossils dug from caves and gravels across the Harz region. Its “horn” evoked medieval trade in supposed unicorn trophies, while the rest of the frame was cobbled from whatever looked suitably grand. Early viewers saw confirmation of a cherished myth; modern researchers see a case study in how cultural expectations can bend bone into fantasy. That pivot – from spectacle to scrutiny – is the pulse of this story.

Today, specialists spot telltale signs a casual observer would miss: the way a limb joint doesn’t match its socket, the mismatch in size between pelvis and vertebrae, and the distinctive texture of Ice Age bone. Comparative anatomy, meticulous measurements, and reference collections let them catch these inconsistencies quickly. And once you see them, you can’t unsee them.

A Cave With a Long Memory

The trail leads to Germany’s Unicorn Cave in the Harz Mountains, a place whose very name hints at centuries of hopeful misreadings. For generations, ground-up fossils from the cave were sold as “unicorn powder,” a cure-all whose magic fades under any microscope. Yet the site is no curiosity shop; it’s a serious paleolithic archive, layered with bones and traces of ancient climate. Excavations over the past decades have revived its scientific profile and tightened the timeline of who used the cave and when. That revival reshapes how we place the Magdeburg spectacle in context.

Recent work at the cave unveiled cultural surprises alongside the biology, including ornamented bone artifacts dated to the deep Ice Age and linked to Neanderthal craft. Finds like these turn a once-mythic cavern into a working laboratory for human history, climate shifts, and megafaunal ecology. The cave keeps saying, look again – there’s more here than legend.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

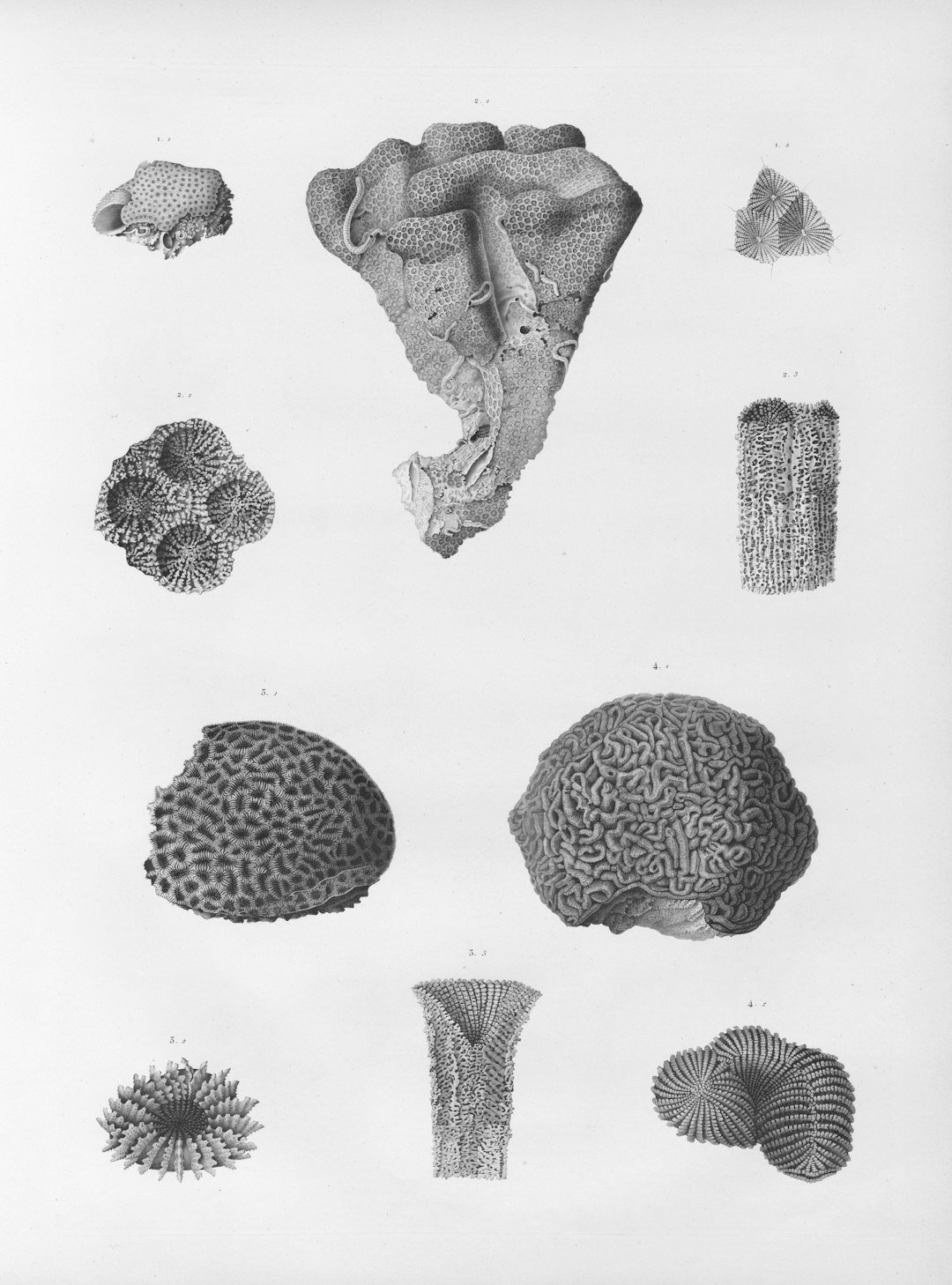

Seventeenth-century naturalists had curiosity and courage, but they lacked today’s toolkit. Modern researchers can radiocarbon-date bone collagen to anchor fossils in time, scan fragments with micro-CT to model hidden structures, and use peptide fingerprinting to tell a rhinoceros shard from a bison sliver. When conditions allow, ancient DNA and isotope chemistry trace species identity, diets, and migrations across Ice Age landscapes. Each technique answers a different question, and together they turn guesswork into evidence.

That’s how the unicorn unravels: by showing its seams. Mixed ages, mismatched anatomies, and incompatible species reveal a composite built for drama, not accuracy. And instead of being embarrassing, that conclusion is liberating – because it demonstrates how evidence outgrows folklore.

Rebuilding the Beast

Rebuilding The Beast (image credits: wikimedia)

Take a closer look at the parts scholars now associate with the display: thick-limbed bones reminiscent of mammoths, sturdy pelvis pieces like those of cave bears, and skull fragments aligned with woolly rhinoceroses. No single Ice Age animal wore a needle-straight horn on its brow; rhinoceros horns are keratin and don’t fossilize, while mammoth tusks curve, and deer antlers branch. The original assemblers weren’t lying so much as curating wonder from the fossil cabinet they had, guided by stories they loved. Their reconstruction was a thought experiment rendered in bone.

In the lab and museum today, experts sketch how those pieces truly fit on their original owners, then compare the fits against known skeletons. What emerges is not a unicorn, but a crowd of vanished species that once roamed cold grasslands and conifer forests. That crowd is richer than a single horn could ever be.

The Hidden Ledger of Evidence

If you map the paper trail, you watch perception evolve from marvel to method. Early engravings turned the composite into a tidy silhouette; later catalogs began to flag oddities; and present-day checklists join the dots with measurable standards. The lesson is that provenance – where a bone comes from, layer by layer – matters as much as dazzling display. It’s a reminder that collections are stories written with fragments, and footnotes matter as much as headlines.

- Seventeenth-century cabinets often mixed fossils from multiple sites, then backfilled gaps with imagination.

- Ice Age bones can differ in color, density, and mineralization even within the same cave, signaling different ages.

- Modern curation logs now track each fragment’s context, helping prevent new composites from repeating old mistakes.

Why It Matters

Accuracy isn’t just a museum etiquette; it’s how we reconstruct vanished worlds and test big ideas about extinction, climate, and human presence. A composite unicorn shifts from a magical one-off to a cautionary exemplar of confirmation bias – an everyday hazard in science, not just history. Compared with traditional display-first approaches, today’s research-first model asks the harder question: what’s the minimum claim we can defend with evidence? That ethos protects the public trust that museums and journals depend on.

There’s also a cultural dimension: legends do useful work by attracting attention, but they need a handoff to analysis before they harden into misinformation. In that handoff, the Magdeburg Unicorn earns a second life as a teaching tool about skepticism, method, and the joy of being proven wrong by better data. The payoff is a cleaner map of the Ice Age, one bone at a time.

Global Perspectives

The Magdeburg episode fits a wider pattern: famous misreads that ultimately sharpened the scientific method. Early reconstructions of Iguanodon gave it a horn on its nose rather than a spike on its thumb; the correction rewrote dinosaur posture and behavior. Traders once sold narwhal tusks across Europe as unicorn horns, a reminder that markets can reinforce myths as effectively as manuscripts. And the Piltdown forgery – fossil fragments stained to fake a “missing link” – accelerated the development of forensic checks that now catch anomalies quickly.

Seen together, these cases argue for patience and redundancy in evidence. Multiple lines of data, independent labs, and transparent archives make it harder for a beautiful story to outrun the facts. The result isn’t dull; it’s resilient science that survives trend and temptation.

The Future Landscape

The Future Lnadscape (imagecredits :wikimedia)

Tomorrow’s unicorn-slayer is computation married to careful fieldwork. Machine-learning models trained on vast skeletal datasets can flag mismatched bones in seconds, while 3D scanning archives fragile fossils so teams can “rebuild” creatures virtually without risking the originals. Proteomic tools that read collagen signatures, and isotope maps that trace ancient water and plants, will keep tightening species IDs and landscapes. Even cave sediments now yield environmental DNA, letting researchers find species that left no bones at all.

The challenges are less technical than social: sustaining funding for long-term digs, expanding open databases that share scans and measurements, and building consent-driven collaborations with local communities and landowners. If we get that right, the next generation will inherit not just better tools, but better habits. That’s how myths fade gracefully while wonder remains.

Conclusion

Start local: visit your nearest natural history museum and read the labels with a detective’s eye, noticing how curators describe uncertainty as well as confidence. Support open-science projects that digitize collections, because high-quality scans and public databases help researchers test old claims without moving fragile bones. If you donate, favor organizations that commit to long-term cave and karst conservation, where fossils and sediments are easily damaged but irreplaceable. And when a sensational headline appears, share it with a question rather than a conclusion – curiosity is contagious, and it’s the best safeguard against our own wishful thinking.

You don’t have to disown legends to love evidence. Keep the story, but let the data drive it. That’s the real magic the Magdeburg Unicorn leaves behind.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.