Picture this: you’re standing at the edge of a prehistoric swamp 95 million years ago, and a powerful creature emerges from the murky water. Fast forward to today, walk up to any modern zoo, and you’d see virtually the same animal staring back at you. If we were to go back in time 95 million years, we would find that the crocodile’s appearance would be unchanged. It’s enough to make you wonder if crocodiles discovered the secret to evolutionary perfection.

But here’s where things get interesting. While most animals have undergone dramatic transformations over millions of years, crocodiles seem to have hit the evolutionary jackpot early and stuck with their winning formula. What makes this even more fascinating is that they’ve survived multiple mass extinctions, ice ages, and the rise and fall of the dinosaurs. There’s clearly something remarkable about their biological blueprint that keeps working, generation after generation.

The Evolutionary Paradox of Living Fossils

Today, there are only 25 different crocodile species, a stark difference in diversity compared to birds, which appeared on the fossil record millions of years after crocodiles did but have since evolved into 10,000 other species. This incredible difference raises a compelling question about evolutionary success. While birds exploded into an amazing variety of forms and lifestyles, crocodiles maintained their basic body plan with remarkable consistency.

Paleontology has undeniably shown that these archosaurs are far from the “living fossils” we love to portray them as. Paleontologist Julia Molnar and her coauthors set the record straight in the very first line of their latest paper. The reality is far more complex than the simple “unchanged for millions of years” narrative we often hear. What we’re actually witnessing is a masterclass in evolutionary efficiency rather than evolutionary stagnation.

Punctuated Equilibrium: The Stop-Start Pattern

In a study published this month in Communications Biology, researchers of the University of Bristol found crocodiles have kept their distinct features over millions of years and lack diversity because of punctuated equilibrium, or long periods where species are stable. Think of it like a classic car that’s been so well-designed that it never needs major updates – just minor tweaks here and there to keep it running perfectly.

This pattern of low evolutionary rates interrupted by occasional bursts of activity is known as “punctuated equilibrium”. This is what we would expect to see in cases where evolution is being driven by external factors like mass extinctions or climate change, rather than intrinsic forces like sexual selection or the arms race between predators and prey. During stable periods, crocodiles essentially coast along with their tried-and-true design. But when the environment throws them a curveball, they can surprisingly adapt quickly.

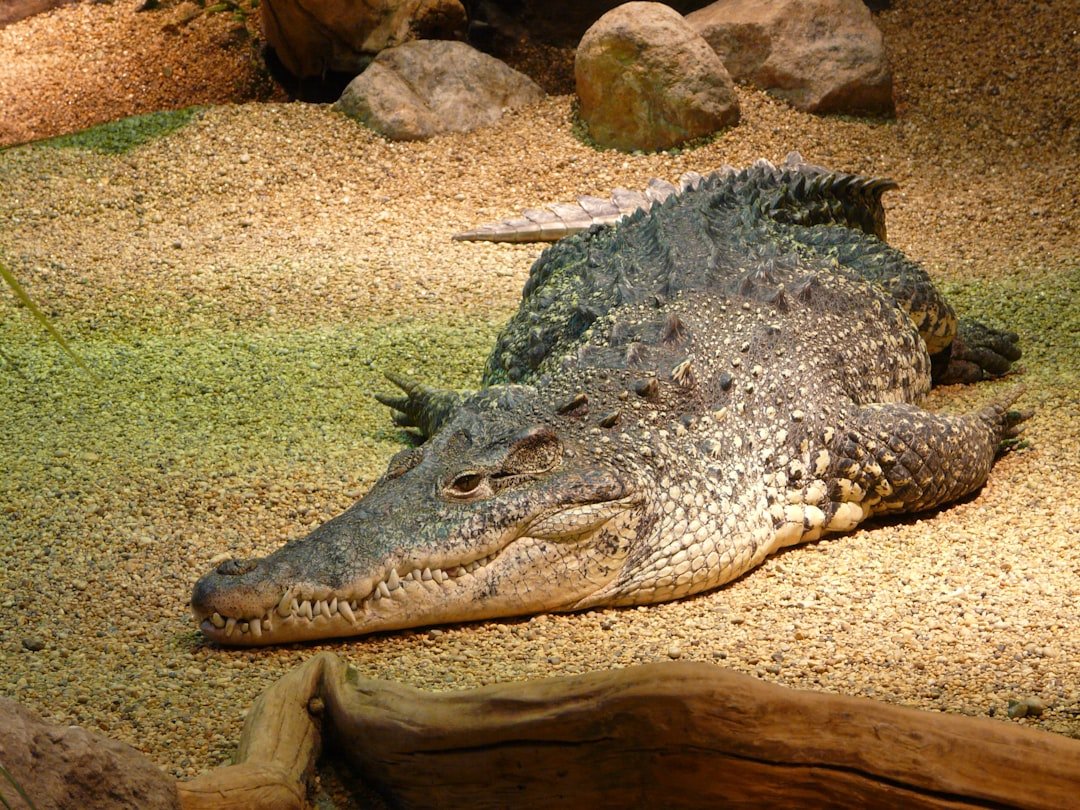

The Perfect Amphibious Design

They share a unique body form that allows the eyes, ears, and nostrils to be above the water surface while most of the animal is hidden below. The tail is long and massive, and the skin is thick and plated. It’s like nature designed the ultimate stealth submarine that can also function perfectly on land.

The external nostril openings, the eyes, and the ear openings are the highest parts of the head. These important sense organs remain above the water surface even when the rest of the head and body are submerged. This positioning isn’t just convenient – it’s evolutionary genius. While their prey focuses on what’s visible above water, nearly their entire predatory arsenal remains hidden below the surface, ready to strike with devastating speed and power.

Armor That Actually Works

With few natural predators, a permanent armor of bony plates covering most of its body and strong jaw muscles capable of crushing anything from bones to cast iron, the croc is an extremely tough and robust creature. Their protective armor isn’t just for show – it’s a sophisticated defensive system that’s proven its worth across geological time periods.

A croc can survive even after serious injuries such as a torn off limbs or tail and has a powerful immune system that helps it survive for decades. This incredible resilience means that individual crocodiles can live long enough to pass on their successful genes, even after surviving encounters that would be fatal to most other animals. Their armor and healing abilities work together like a biological insurance policy.

The Energy-Efficient Lifestyle

One of the keys to its survival is something one might think of as primitive: cold-bloodedness. Like all reptiles, crocs are ectotherms, which means they must gather heat from their environment. While warm-blooded animals burn through calories just to maintain their body temperature, crocodiles have mastered the art of energy conservation.

Crocodilians have a very low metabolic rate and thus low energy requirements. They can withstand extended fasting by living on stored fat. Imagine being able to skip meals for months without any significant health consequences. This metabolic efficiency means crocodiles can thrive in environments where food might be scarce, giving them a massive survival advantage during tough times.

Bite Force Beyond Belief

Based on regression of mean body mass versus mean bite force, the bite force of a 6.7 m (22 ft) saltwater crocodile with an estimated mass of 1,308 kg (2,884 lb) was estimated at between 6,187 lbf (27,520 N) and 7,736 lbf (34,410 N). To put this in perspective, that’s roughly equivalent to the weight of a pickup truck concentrated into the space of a crocodile’s jaw.

The extraordinary bite of crocodilians is a result of their anatomy. The space for the jaw muscle in the skull is very large, which is easily visible from the outside as a bulge at each side. This isn’t just raw power for the sake of it – it’s precision engineering that allows crocodiles to take down prey much larger than themselves. Their skull design maximizes the mechanical advantage of their jaw muscles, creating one of nature’s most effective crushing mechanisms.

Temperature-Driven Evolution

In particular, the researchers found that the evolution of crocodiles is accelerated in a warmer climate, and their body size increases. This relationship between temperature and evolutionary change provides crucial insights into how crocodiles might respond to our current climate changes.

The more rapidly evolving species didn’t appear independently, instead tending to emerge together when the climate was warmer. Warmer periods in Earth’s history seem to act like evolutionary accelerators for crocodiles, triggering bursts of adaptation and diversification. During cooler periods, they return to their stable, energy-efficient baseline – a strategy that’s served them remarkably well across multiple climate cycles.

The Digestive Powerhouse

A croc’s stomach is the most acidic of all vertebrates, allowing it to digest bones, horns, hooves, or shells. Nothing gets left behind in a crocodile’s dinner. Their digestive system is essentially a biological waste disposal unit that can break down materials that would be completely inedible to most other animals.

The stomach is more acidic than that of any other vertebrate and contains ridges for gastroliths, which play a role in the crushing of food. These “gizzard stones” work like an internal grinding system, helping to pulverize tough materials that even their powerful jaws can’t completely crush. It’s a two-stage destruction system that maximizes the nutritional value they can extract from each meal.

Sensory Superiority

Like many nocturnal animals, crocodiles have eyes with vertical, slit-shaped pupils; these narrow in bright light and widen in darkness, thus controlling the amount of light that enters. On the back wall of the eye, the tapetum lucidum reflects incoming light, thus utilizing the small amount of light available at night to best advantage. Their vision system is perfectly adapted for their ambush lifestyle, allowing them to hunt effectively in low-light conditions when many prey animals are most vulnerable.

Unlike the ears of other modern reptiles, those of the crocodile have a movable, external membranous flap that protects the ears from the water. These protective flaps work like biological diving equipment, sealing their ears when they submerge while still allowing them to hear approaching prey or threats when at the surface. Their sensory adaptations represent millions of years of fine-tuning for their specific environmental niche.

Hidden Evolutionary Diversity

Despite the variation in skull shape and diet among alligatorids, crocodylids, and gavialids, extant crocodilians represent only a small fraction of the diversity of their extinct relatives. At various times in their long history, crocs have evolved into tiny insect-eaters, long-legged terrestrial runners, and pug-nosed, armored herbivores. The crocodilian family tree is far more diverse and fascinating than their current representatives might suggest.

By this point, a once marvelously motley tribe of reptiles – of swimmers, sprinters, and tree-climbers, of the lizardy, cat-like, and pug-nosed – had dwindled to a handful of survivors. Those fortunate few colonized tropics around the world, most likely by embarking on epic ocean journeys. Today’s crocodiles are essentially the championship survivors of a much larger evolutionary experiment – the descendants of the few lineages tough enough to weather multiple extinction events and climate changes.

The Future of Crocodilian Evolution

Our research strongly suggests crocodilians have remained unchanged for such a very long time because they have landed upon an equilibrium state that does not require them to change often. When crocodilian evolution does happen at pace, it is likely that this is because the environment has changed and has forced them to adapt. As our planet faces rapid climate change, we might actually witness crocodiles breaking out of their stable evolutionary pattern and adapting in real time.

As temperatures warm up here, we will start to see alligators in more middle-northerly watersheds of the Mississippi River. While they’re known to be in some rivers in southern Arkansas and Tennessee now, we can likely expect them in our waterways here in Missouri in the coming decades. Climate change might trigger the next chapter in crocodilian evolution, potentially leading to new adaptations as they expand into previously unsuitable habitats.

So, did you expect that the story of “unchanged” crocodiles would actually reveal one of evolution’s most sophisticated success strategies? These ancient survivors haven’t remained static – they’ve simply mastered the art of knowing when not to change.