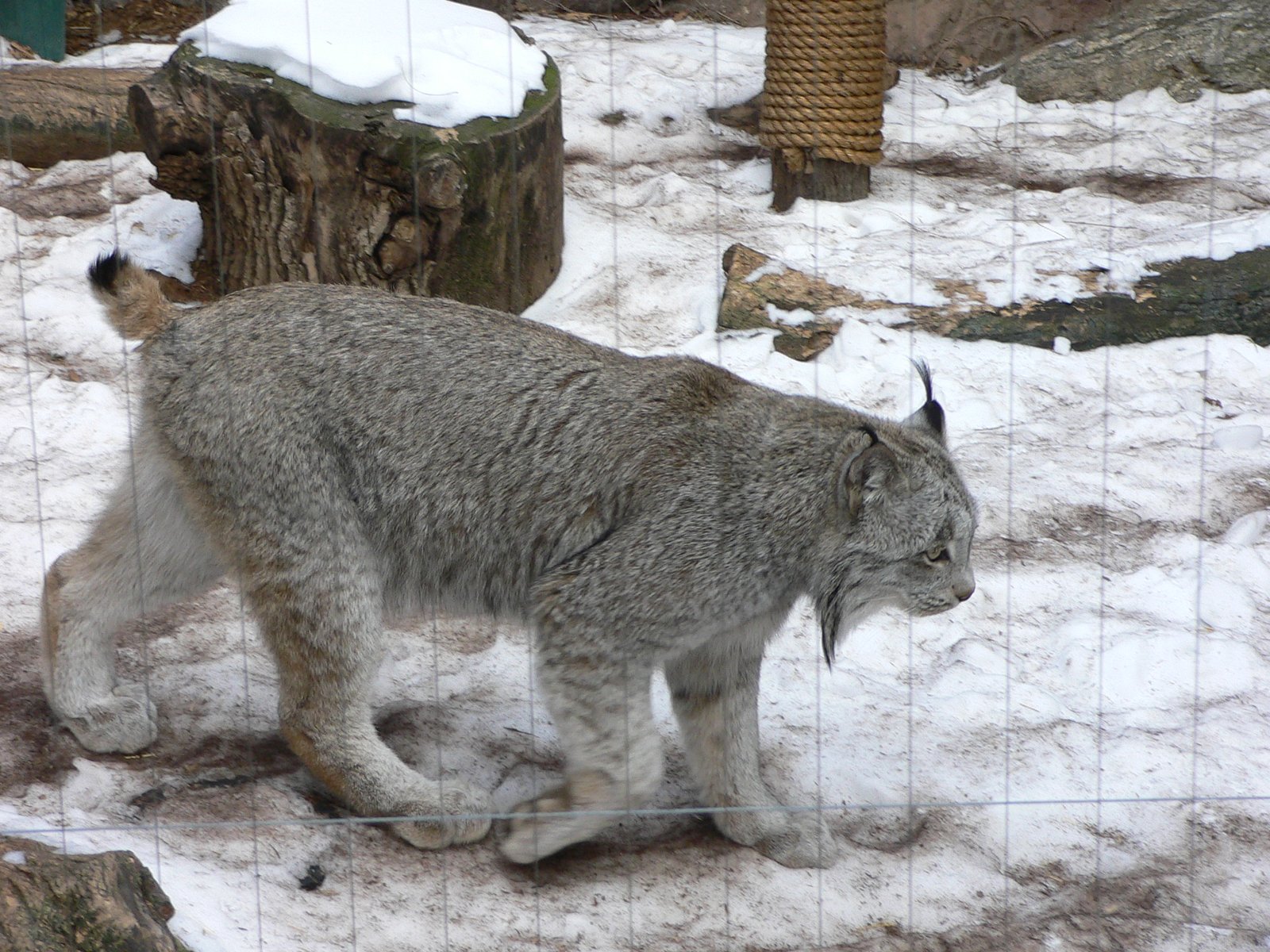

The ghostly shadows prowling through ‘s snowy mountain forests tell one of the most remarkable conservation stories of our time. After vanishing from the state’s wilderness for decades, the Canada lynx has made an extraordinary comeback that has wildlife biologists around the world taking notice. This isn’t just another feel-good wildlife story – it’s a testament to what happens when science, determination, and nature itself work together to bring a species back from the brink. Picture this: elusive wildcats with snowshoe-sized paws, threading their way through dense spruce forests at elevations where the air grows thin and snow blankets the ground for months. These aren’t your typical house cats – they’re specialized mountain hunters that had seemingly disappeared forever from ‘s landscape. Yet today, somewhere between seventy-five and one hundred of these remarkable creatures are thriving in the state’s high-elevation wilderness, their presence confirmed through cutting-edge tracking technology and old-fashioned detective work in the snow.

The Great Disappearance and Dramatic Return

By the late 1800s, lynx roamed most of Colorado’s high-elevation forested areas, but by 1930 they had become rare, and by the mid-1970s the population was virtually extinct. Trapping, poisoning, and habitat loss drove these magnificent cats to complete disappearance from the state. The situation seemed hopeless – another casualty of human expansion and the relentless march of development. But in the late 1990s, Colorado Parks and Wildlife launched an ambitious seven-year reintroduction effort, releasing 218 lynx captured from Alaska and Canadian provinces between 1999 and 2006 in the San Juan Mountains. This wasn’t just any conservation project – it was the first-ever lynx reintroduction attempt anywhere in the world. The stakes couldn’t have been higher, and every eye in the conservation community was watching Colorado’s bold experiment.

Early Setbacks and Hard-Learned Lessons

The initial release in 1999 faced immediate challenges, with nine animals dying in the first year, mostly from starvation, and two killed by vehicles on Interstate 70. Wildlife biologist Scott Wait recalls the grim early days: “I know there were four starvations out of that first batch of about eight”. These weren’t just statistics – each loss represented months of careful planning and a significant blow to the program’s hopes. Learning from these early failures, wildlife managers completely changed their approach, holding captured lynx in captivity for longer periods and fattening them up before releasing them in late winter and early spring, just before breeding season. This adjustment led to dramatically improved post-release survival rates. Sometimes the best lessons come from the hardest failures, and Colorado’s lynx program proved that persistence and adaptability could turn disaster into triumph.

The Technology Behind Tracking Success

All 218 lynx released in Colorado were fitted with radio and satellite collars, allowing researchers to track each individual animal’s movements and survival. This wasn’t your grandfather’s wildlife tracking – these high-tech devices revolutionized how scientists could monitor the reintroduced population. GPS collars, developed in the 1990s, collect and store massive amounts of location information while providing detailed data about animal movement patterns and survival rates. Colorado Parks and Wildlife stopped using tracking collars in 2011, transitioning to a combination of motion-sensor cameras and field monitoring by biologists. The technology shift reflected both the program’s success and the need for less intrusive monitoring methods. Today’s approach combines cutting-edge camera traps with old-school snow tracking, creating a comprehensive picture of where these elusive cats are thriving.

Camera Traps Reveal Hidden Lives

For wilderness area surveys, researchers determined that remotely triggered wildlife cameras were the most efficient method for detecting lynx, with plans to survey fifty units annually in the San Juan and South San Juan Mountains. Biologists randomly selected fifty study units, each measuring about twenty-nine square miles and divided into quadrants, with one camera placed in each quadrant. More than 100,000 photos are captured each winter season, showing elk, deer, bears, mountain lions, coyotes, and other wildlife, but finding lynx photos requires painstaking examination. To ensure accurate identification, two people examine each photo, and on average, only eight to fourteen cameras capture lynx images throughout an entire winter. It’s like searching for needles in a haystack, except the needles have four legs and prefer to avoid cameras entirely.

Snow Tracking: The Old-School Detective Work

During winter months, biologists and wildlife officers survey study plots on skis or snowmobiles, looking for tracks and collecting lynx scat and hair for genetic analysis. Colorado’s rugged topography makes tracking an arduous undertaking, especially in winter when snow creates detailed activity records, but the work is labor-intensive. Forest Service wildlife biologist Anthony Garcia covers 180 miles divided into eighteen sections at elevations ranging from 8,000 to 11,000 feet, tracking not only lynx but also pine marten, snowshoe hare, and squirrels. Biologists employ statistical techniques, combining snow-tracking results with camera images to estimate occupancy rates, assuming that more occupied areas indicate a healthy, expanding population. This detective work in the snow provides crucial data that high-tech gadgets simply can’t match.

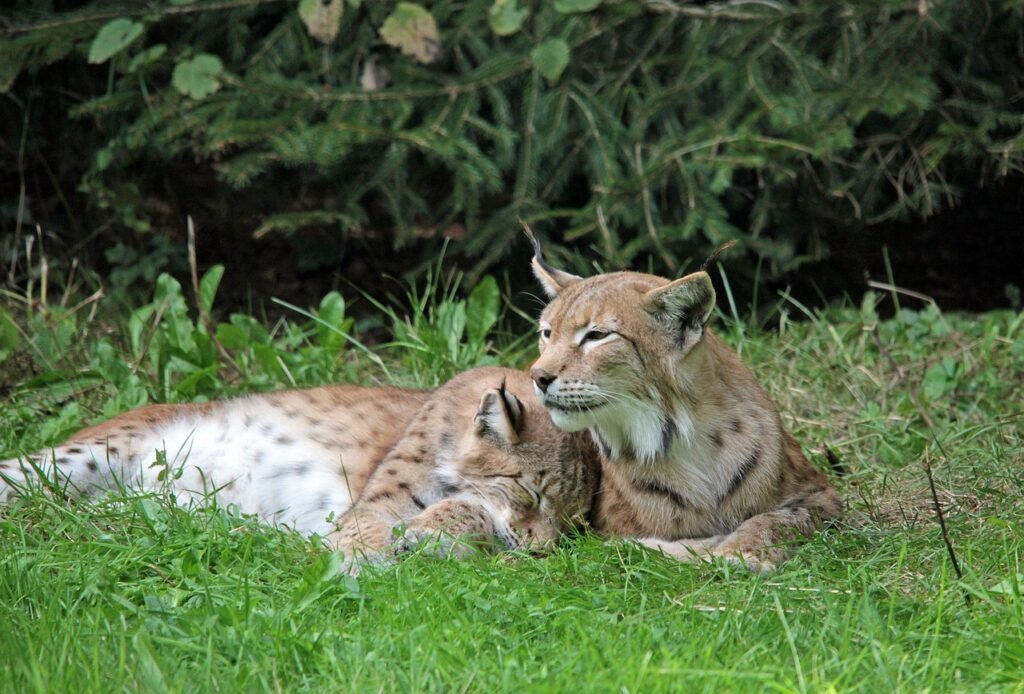

Breeding Success and Population Cycles

Colorado Parks and Wildlife released additional lynx between 2003 and 2006 to encourage breeding, and researchers documented the first sixteen kittens born to reintroduced lynx in 2003. Third-generation cats – the grandchildren of the original transplants – were first documented in 2006, proving that the population was truly establishing itself in Colorado’s wilderness. Lynx reproduction varied dramatically, from a high of fifty kittens in 2005 to no reproduction in 2007 and 2008, with such wide swings being typical of lynx populations in Alaska and Canada, where birth rates fluctuate with snowshoe hare abundance. Colorado observations show a pattern of several years of higher reproductive success followed by lower reproduction years, with prey abundance variation being one potential explanation. Nature rarely follows human schedules, and lynx populations remind us that wildlife conservation requires patience and understanding of natural cycles.

Modern Population Status and Distribution

Current monitoring efforts suggest Colorado is home to seventy-five to one hundred individual lynx with evidence of stable distribution and successful reproduction in the wild. Some estimates place the current population at around two hundred lynx occupying the San Juans, with more dispersed throughout the state, though precise population counts would be prohibitively expensive due to the species’ elusive nature and remote habitat preferences. Today, Canada lynx are primarily found in the San Juan Mountains and Sawatch Range of western Colorado. While the core population remains stable in the San Juan Mountains, lynx have expanded beyond this area, with regular sightings reported in Colorado’s central mountains, leading to considerations for expanded monitoring. The cats have essentially voted with their paws, choosing to explore new territories as their numbers have grown.

Climate Change: The Looming Challenge

Canada lynx depend on snowy forests with dense understory where their primary prey, snowshoe hares, thrive, but in Colorado these habitats are limited to small, scattered areas on mountain slopes, making lynx especially vulnerable to wildfires, development, and climate change. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recognizes that projected global climate warming presents the greatest challenge to long-term lynx conservation, with climate-driven losses likely to make lynx populations smaller and more patchily distributed, making long-term conservation uncertain without progress on reducing global warming trends. Lynx live in cold boreal forests and prey primarily on snowshoe hares, but climate change is melting away their snowy habitat and could decrease hare availability, with lynx declines expected across the contiguous United States under even the most optimistic warming scenarios. Scientists worry about the persistence of Colorado’s relatively few and somewhat isolated habitat patches within a timeframe sufficient to have demographic and conservation consequences. It’s a race against time, with rising temperatures threatening to undo decades of conservation success.

Wildfire: The Greatest Natural Threat

High-severity wildfires pose the greatest threat to lynx habitat, destroying the forest understory that lynx rely on for hunting and shelter, and while only five percent of likely habitat has been impacted to date, the annual wildfire risk is elevated due to climate change, with recovery taking decades in Colorado’s subalpine forests. While documented fire events have the lowest overlap with lynx habitat currently, wildfire likely represents the greatest threat to lynx habitat over decades due to increasing fire size, severity, and frequency from climate change. Beetle outbreaks impact forests but often leave enough young trees to sustain lynx prey, making their effects less severe than wildfires, while development and ski area expansions overlap with only four percent of likely lynx habitat, but these changes are permanent and require careful management. The irony is striking – the very wilderness that provides refuge for lynx is increasingly under assault from the changing climate that threatens their long-term survival.

Federal Protection Efforts Intensify

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service has released its final twenty-year recovery plan and proposed designating approximately 9,400 square miles as critical habitat across eight states, including numerous Colorado counties including portions of Archuleta, Boulder, Chaffee, Clear Creek, Conejos, Dolores, Eagle, Gilpin, Grand, Gunnison, Hinsdale, La Plata, Lake, Mineral, Montezuma, Montrose, Ouray, Park, Pitkin, Rio Grande, Saguache, San Juan, San Miguel, and Summit counties. Critical habitat is defined as areas supporting long-term occupancy and reproduction, including adequate snowshoe hare populations, dense boreal and subalpine forests, and extended winter conditions. Southwestern Colorado is now home to one of only five breeding populations of Canadian lynx in the entire country, with other populations existing in northern Maine and northeastern New Hampshire, northeastern Minnesota, northwestern Montana and northern Idaho, and north-central Washington. There are roughly 1,000-1,200 lynx in the contiguous United States spread across five populations, with officials aiming for a minimum population of 875 lynx over a twenty-year period. Colorado’s success story has become a crucial piece of the species’ survival puzzle.

Scientific Recognition and Future Research

In 2010, Colorado Parks and Wildlife declared the reintroduction project met all benchmarks of success, including high survival rates after release, successful reproduction in released animals and wild-born animals, low mortality rates, and reproduction rates equal to or exceeding mortality rates over extended periods. Conservation biologist Megan Mueller calls it “one of the most successful reintroductions of a threatened species”, while scientists consider Colorado’s efforts to reintroduce and study lynx one of the most high-profile and successful conservation efforts ever. A new study published in mid-December 2024, titled “Anthropogenically protected but naturally disturbed: a specialist carnivore at its southern range periphery,” provides valuable insights into managing sensitive species in landscapes increasingly structured by complex disturbance patterns accelerated by climate change. These findings refine understanding of lynx habitat and help focus conservation efforts where they are needed most. The research represents more than academic interest – it’s a roadmap for the species’ future survival.

A Conservation Success with Ongoing Challenges

Colorado’s lynx reintroduction stands as proof that dedicated conservation efforts can bring species back from the brink of extinction. Wildlife officials declared victory in their eleven-year effort to reintroduce lynx, noting that the cats are reproducing faster than they’re dying – the hallmark of a self-sustaining population. Monitoring shows the population in the San Juan Mountains is stable, yet the story is far from over. Colorado Parks and Wildlife remains committed to protecting Canada lynx and their habitat through science-based management, proactive wildfire mitigation, and sustainable land-use planning, working with partners and local communities to build a future where lynx can continue to thrive in Colorado’s iconic landscapes. The success of this program has rippled far beyond Colorado’s borders, providing valuable lessons for wildlife reintroduction efforts worldwide and proving that with enough determination, scientific rigor, and respect for natural processes, we can indeed help nature heal itself. What started as an ambitious gamble has become one of conservation’s greatest success stories, yet the challenges ahead – from climate change to habitat fragmentation – remind us that protecting wildlife requires constant vigilance and adaptation. What do you think about this remarkable comeback story? Have you ever spotted one of these elusive cats in Colorado’s wilderness? Tell us in the comments.

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.