Time travel sits in that strange space between serious physics and wild science fiction. On one hand, it feels like something from a late-night movie marathon; on the other, some of the best minds in physics have written real equations suggesting ways it might actually work. The more you dig into it, the more unsettling it gets: our familiar ideas of cause and effect start to wobble, and you quickly bump into questions that sound more like philosophy than math.

But underneath all the drama are very precise theories, especially Einstein’s relativity, that tell us where time travel might be allowed and where it probably breaks down. The catch is that every potential doorway through time comes with a mess of paradoxes: impossible loops, broken histories, and events that seem to cause themselves. Let’s walk through the physics that opens the door to time travel, and the paradoxes that slam it shut again – or twist it into something far stranger.

The Strange Way Relativity Already Bends Time

The surprising truth is that a mild form of “time travel” is already baked into modern physics: it’s called time dilation. According to Einstein’s special relativity, time can tick at different rates for different observers depending on their motion. If you travel in a spaceship at a speed close to the speed of light and then come back, less time will have passed for you than for the people who stayed on Earth, a scenario often called the twin paradox.

This isn’t just theory; it’s been measured with extremely accurate atomic clocks on airplanes and satellites. Astronauts on the International Space Station age a tiny bit less than people on the ground because they move fast and are slightly farther from Earth’s gravity. General relativity adds another twist: gravity itself slows time, so clocks near massive objects tick slower than clocks farther away. In that sense, the universe already lets us move into the future at different rates – it just doesn’t (as far as we know) let us hop back into the past.

Closed Timelike Curves: When Spacetime Loops Back

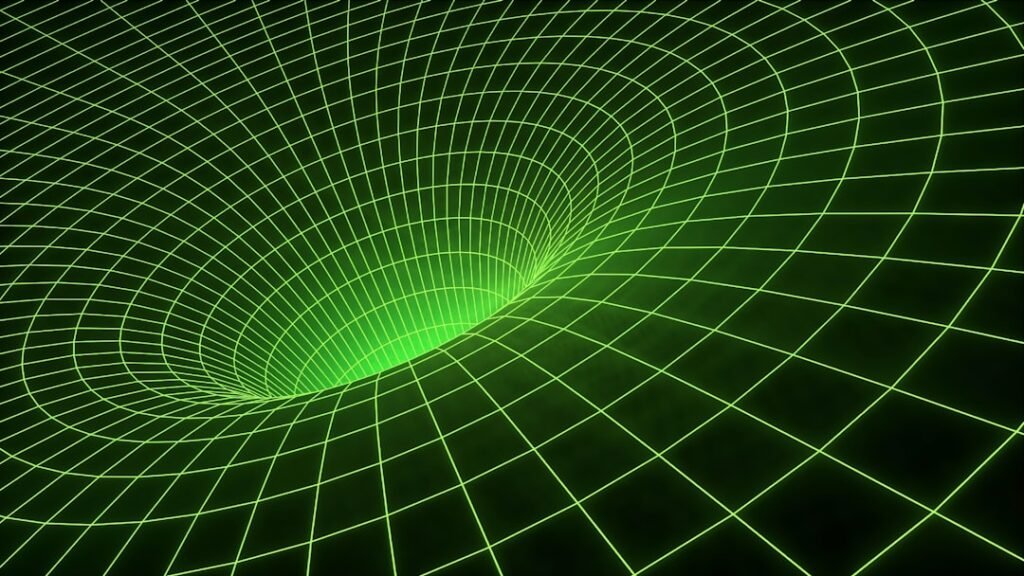

In general relativity, spacetime isn’t a rigid stage; it can bend, twist, and even fold back on itself in bizarre ways. Mathematically, this opens the door to what are called closed timelike curves, paths through spacetime that bring an object back to the same point in both space and time. If such curves exist in reality, you could in principle travel along one and literally return to your own past. That’s not just sci-fi hand-waving; some exact solutions to Einstein’s equations allow these loops.

Certain theoretical constructs – like rotating universes, rapidly spinning black holes, or exotic matter configurations – can generate these closed timelike curves in the math. The problem is that almost all of these scenarios require conditions the real universe doesn’t seem eager to provide, such as extremely precise rotations or forms of matter with negative energy. Still, the mere existence of these solutions is enough to make physicists sweat, because they suggest that, at least on paper, the laws of relativity don’t strictly forbid time machines.

Grandfather Paradoxes and the Problem of Cause and Effect

The moment you allow trips into the past, you crash headfirst into the classic paradoxes. The most famous is the so‑called grandfather paradox: if you travel back in time and prevent one of your grandparents from having children, you would prevent your own birth – so who went back in time to do the preventing? This isn’t just a cute puzzle; it attacks the core of causality, the idea that causes come before effects in a clear, consistent chain.

In physics, causality underpins almost everything, from everyday mechanics to quantum theory. If events in the future can erase the conditions that allowed them to happen, the whole structure of prediction and explanation starts to fall apart. Many physicists suspect that any consistent theory of nature must block exactly this kind of loop. That’s where ideas like “consistency constraints” enter the picture: if time travel is allowed, then perhaps the universe simply never lets you create a real contradiction in the first place.

The Novikov Principle: The Universe Refuses a Contradiction

One proposed escape from paradox is the idea that the universe is “self-consistent” by design. In this view, you can travel into the past, but anything you do there was always part of history; you can’t change the past, you can only fulfill it. So if you go back intending to stop your grandparents from meeting, something always goes wrong – your plan misfires, circumstances intervene, or your actions accidentally cause the very meeting you wanted to prevent. The loop closes, but in a logically consistent way.

This idea is often called the Novikov self-consistency principle, and it treats paradoxes not as impossible situations but as events that simply never occur because the probability of them happening is effectively zero. From a storytelling perspective, it feels almost cruel: you have free will, but every attempt to break history fails. From a physics standpoint, it’s a way to keep closed timelike curves without throwing out causality altogether, though it turns the universe into something that behaves more like a carefully edited script than a free-flowing improvisation.

Many Worlds: Every Time Trip Splits Reality

Another route out of paradox reaches into the quantum world and the idea that multiple realities might coexist. In the many‑worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, every quantum event with different possible outcomes effectively splits reality into different branches. Applied to time travel, this suggests a different picture: if you travel into the past and make a change, you don’t rewrite your original history – you slide into a different branch where the past unfolds differently.

In that scenario, the grandfather paradox dissolves because your actions affect a version of your grandparents in another branch, not the ones that led to your own existence. Your original timeline remains untouched, sitting on its own track, while you create or join another. This doesn’t make time travel simple, though; it replaces one headache with another, raising questions about how these branches connect, whether they can be re-joined, and what it even means for a person to move between them. Still, it offers a way to preserve both causality and the freedom to genuinely alter a past.

Wormholes, Exotic Matter, and the Energy Problem

When people talk about “realistic” time machines in physics, wormholes almost always show up. A wormhole is a hypothetical tunnel through spacetime, linking two distant regions like a shortcut. If you could create or stabilize a wormhole and then move one mouth at high speed or into a strong gravitational field, time dilation would cause the two ends to age differently. Bring them back together, and you’d have a time shift between the mouths – a kind of two-way time gate.

The catch is that every plausible wormhole design needs something nature has never clearly shown us: exotic matter with negative energy density to keep the throat from collapsing. Quantum physics hints that small amounts of negative energy might exist in certain effects, but nothing like the huge, controlled quantities you’d need for a human-scale wormhole. On top of that, attempts to turn such devices into full-fledged time machines often seem to trigger instabilities where quantum fluctuations surge and rip the structure apart. It’s as if the universe tries to slam the door shut right when you’re about to step through.

Does Physics Protect the Timeline? Chronology Protection

Because of all these issues, some physicists suspect that a deeper principle is at work, quietly defending cause and effect. This idea is sometimes summarized as “chronology protection” – the notion that the laws of quantum gravity (the still‑unfinished theory uniting quantum mechanics with general relativity) will ultimately forbid true time machines. In many calculations, whenever a would‑be time loop forms, quantum effects become so intense that spacetime geometry gets wrecked before a paradox can occur.

We don’t yet have a full theory of quantum gravity, so this is more informed expectation than proven law, but it fits a pattern: each time we push the equations toward paradox, something breaks down or demands conditions that look wildly unrealistic. From one angle, that’s disappointing for anyone who grew up dreaming of stepping into a time machine. From another, it’s strangely reassuring that the universe may be structured to keep history from turning into a chaotic snarl of self‑contradictions.

What Time Travel Paradoxes Tell Us About Reality

Time travel is often treated as a fun “what if,” but the paradoxes it raises are more than just mental games. They expose how deeply we rely on a straightforward sense of time: a before and after, a cause and effect, a story that doesn’t loop back and erase itself. When we push our best theories into these extreme scenarios, the friction we feel is a clue that something in our understanding is still incomplete. Even the disagreements between different approaches – self‑consistent histories, many‑worlds branches, or strict chronology protection – are signals about the boundaries of today’s physics.

Personally, I suspect that if we ever manage anything resembling time travel, it will look nothing like the clean machines and tidy trips we imagine in movies. It might be limited to tiny scales, or buried inside high‑energy processes near black holes, or bound up with quantum effects that don’t translate well to human experience. In that sense, time travel paradoxes are like flashlights we shine into the dark corners of our theories, revealing where they still need work. And even if we never build a time machine, the effort to understand why might tell us more about what time really is than any clock ever could.