Ever wondered why learning a new language feels both exhilarating and exhausting at the same time? Your brain is essentially rewiring itself while you’re struggling with verb conjugations and pronunciation. It’s not just about memorizing vocabulary lists or mastering grammar rules. Something far more profound is happening beneath the surface. Your brain is physically changing, creating new pathways, strengthening connections, and even growing in specific regions. Think of it as an invisible transformation that science can now actually measure and visualize.

Let’s be real, most people start learning a language for practical reasons: travel, career opportunities, or maybe impressing someone special. Yet what’s happening inside your skull goes way beyond being able to order coffee in Paris. The journey of acquiring a new tongue triggers a cascade of neurological events that researchers are only beginning to fully understand. So let’s dive in and explore the fascinating science behind what your brain experiences when you embark on this linguistic adventure.

Your Brain Literally Grows New Tissue

Learning a language increases gray matter structure in areas related to language processing and executive function. This isn’t just a metaphor. A study done on monolinguals, early bilinguals, and late bilinguals showed that bilinguals and individuals who are learning a second language have an increased density of grey matter in their left inferior parietal cortex.

What’s remarkable is that this growth happens regardless of when you start. It’s seen in regions like Broca’s area, which handles sentence structure and speech production, and Wernicke’s area, which helps with understanding and recalling words. Think of gray matter as the brain’s processing power. More gray matter means more neurons packed into those regions, which translates to better information processing. Your brain is essentially building more computing capacity in response to the linguistic challenge you’re throwing at it.

White Matter Connections Get Supercharged

While gray matter gets the spotlight, white matter deserves equal attention. These images showed the strengthening of white matter connections within the language network, as well as the involvement of additional regions in the right hemisphere during second language learning. White matter acts like the brain’s highway system, connecting different regions so they can communicate efficiently.

Learning new words strengthened the lexical and phonological subnetworks in both hemispheres, especially in the second half of the learning period, the consolidation phase. Here’s the thing: stronger connections mean faster processing speeds. It’s like upgrading from dial-up internet to fiber optic. The more you practice your new language, the more efficient these communication pathways become, allowing your brain to switch between languages or process complex linguistic information with greater ease.

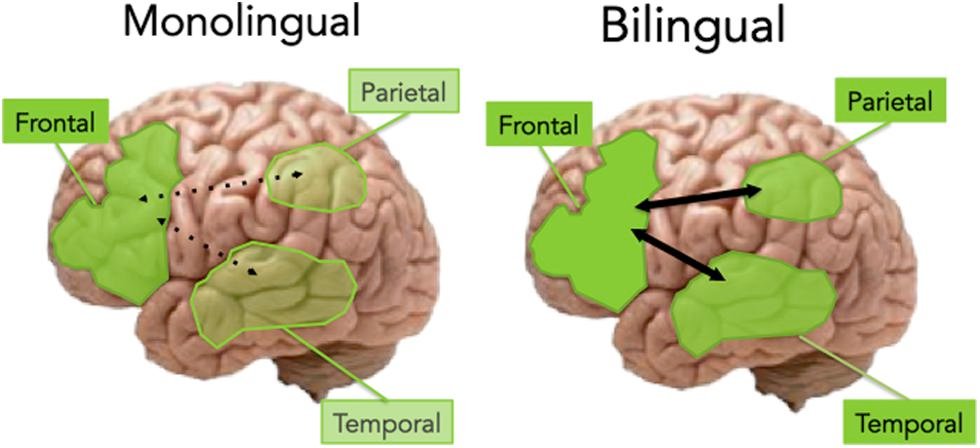

The Left and Right Hemispheres Start Cooperating Differently

Something intriguing happens with how your brain’s two hemispheres work together. The connectivity between language areas in both hemispheres increased with learning progress. This bilateral involvement is fascinating because it shows your brain recruiting resources from both sides to handle the new language.

Surprisingly, researchers also found something counterintuitive. The reduced interhemispheric connectivity suggests that the inhibitory role of the corpus callosum, relevant for native language processing, is reduced in the L2 learning phase. It’s as if your brain needs to loosen the grip your dominant language has, allowing the new language to establish its own territory. This dynamic reorganization shows just how adaptable our brains really are.

Your Memory System Gets a Major Upgrade

Remember struggling to memorize phone numbers before smartphones? Learning a language gives your memory a workout that benefits far more than just vocabulary retention. The hippocampus, crucial for memory and learning, shows enhanced efficiency in bilinguals.

This memory enhancement extends beyond language itself. The act of learning vocabulary and grammar rules in a new language strengthens the memory muscle, making it easier to retain information in general. Bilingual individuals often show better memory retention and recall abilities. It’s like your brain develops better filing and retrieval systems. The constant practice of encoding, storing, and retrieving new words and grammar patterns essentially makes you better at remembering everything from where you left your keys to important dates and appointments.

Attention and Multitasking Abilities Sharpen Dramatically

One of the most practical benefits shows up in how you manage attention. Bilingual students concentrate better, ignoring distractions more effectively than those who only speak one language. This happens because constantly monitoring which language to use in different contexts trains your attentional control systems.

Think about it: when you speak multiple languages, your brain is constantly deciding which words to use and which to suppress. Bilinguals have been found to excel in tasks that require sustained attention and the ability to ignore irrelevant information. This is because managing two languages requires constant monitoring of which language is appropriate to use in a given context, therefore honing the brain’s attentional networks. This mental juggling act translates into better focus in other areas of life. You become better at filtering out distractions and switching between tasks efficiently.

Problem-Solving and Cognitive Flexibility Improve

Learning a new language doesn’t just teach you words and grammar. It fundamentally changes how you think. People who speak more than one language have better attention spans and an increased ability to switch tasks successfully. This is because switching between languages exercises your brain, making it more flexible and better at finding solutions.

Different languages structure reality in different ways. Some languages have grammatical features that others lack entirely. Navigating these differences forces your brain to become more adaptable. Bilingual people often find creative solutions to problems, as the process of learning and using a new language involves constant problem-solving and critical thinking. Navigating different grammatical structures and vocabulary forces the brain to think in diverse ways, which can foster innovative thinking and adaptability. You’re essentially training your brain to see multiple perspectives and approaches to any given challenge.

The Aging Brain Gets a Protective Shield

Here’s where things get really exciting for long-term brain health. Multilingual individuals tended to show slower biological aging than people who spoke only one language. This finding comes from massive studies analyzing tens of thousands of people across multiple countries.

Lifelong bilingualism has been shown to delay the onset of clinical AD by about four years, comparable to the effects of physical fitness and not smoking. Let’s put that in perspective: learning languages might be as protective for your brain as regular exercise is for your body. The cognitive reserve you build through language learning acts like a buffer against age-related decline. Multilingualism boosts the brain’s cognitive reserve, the mental buffer that helps resist age-related decline and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s. Your brain essentially builds backup systems that can compensate when other areas start to decline.

Neuroplasticity Happens at Any Age

Maybe you’re thinking: “This all sounds great, but I’m not a kid anymore. Isn’t it too late?” The research says otherwise. Second language experience-induced brain changes, including increased gray matter density and white matter integrity, can be found in children, young adults, and the elderly; can occur rapidly with short-term language learning or training.

Similar white matter effects are also found in bilingual individuals who learn their second language later in life and are active users of both languages. The brain retains remarkable plasticity throughout life. While children might learn pronunciation more easily, adults bring other advantages like better learning strategies and motivation. The structural changes researchers observe aren’t limited to those who grew up bilingual. Your brain can rewire itself at fifty, sixty, or seventy just as meaningfully as it does in youth.

The Changes Intensify Over Time and Practice

These brain changes don’t happen overnight, but they do happen faster than you might think. Adults who engaged in short-term language study showed significant improvements in their performance on memory and attention tests compared to those who didn’t. Even short-term intensive learning produces measurable changes.

However, the real magic happens with sustained practice. The intensity and diversity of language use influence cortical changes in regions supporting language processing and executive control, whereas the duration of L2 usage promotes neural efficiency, reflected in changes to subcortical structures and white matter pathways. Think of it like building muscle: you’ll see some changes quickly, but the most impressive transformations require consistent effort over months and years. The longer you maintain your language practice, the more deeply entrenched these beneficial brain changes become.

Conclusion: A Gift That Keeps on Giving

Your brain’s response to learning a new language is nothing short of remarkable. From growing new neural tissue to strengthening connections, from boosting memory to protecting against aging, the benefits cascade across virtually every aspect of cognitive function. The science is clear: when you challenge your brain with linguistic learning, it responds by becoming stronger, more flexible, and more resilient.

What makes language learning particularly special is that unlike isolated brain-training games, you’re gaining a practical skill that opens doors to new cultures, people, and ways of thinking. Every conversation you have, every book you read, every stumble through an awkward sentence is sculpting your brain in ways that will serve you for decades to come. The changes we’ve explored aren’t temporary. They’re lasting transformations that compound over time, building a cognitive reserve that may well be one of the best investments you can make in your future self. So what are you waiting for? Have you considered which language might be calling to you?

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.