For decades, the megalodon, a terrible shark that ate only whales has been portrayed as the ultimate oceanic horror, its enormous jaws able to crush a car with a single bite. But shockingly more surprising new studies show Otodus megalodon was not the picky whale specialist we thought of. Rather, it was an opportunistic apex predator that ate everything it could overwhelm including other sharks, dolphins and seals, and even its own kind.

By means of modern isotopic analysis of fossilized teeth, researchers have discovered a dietary flexibility that questions all we know about this prehistoric leviathan. Far from a specialist, megalodon was the ultimate generalist of the ocean, an indiscriminate killer whose eating patterns might have even helped to bring about its own collapse.

The Myth of the Whale-Hunting Superpredator

Paleontologists used to believe megalodon hunted whales mostly years ago. This view was supported by fossil evidence including broken teeth buried in ancient cetacean remains and whale bones marred with megalodon bite marks 16. A surprising turn of events, however, is revealed in a new study appearing in Earth and Planetary Science Letters: megalodon did eat whales, but they were only one item on a far more varied menu.

By analyzing zinc isotopes in fossilized teeth, researchers found that megalodon’s diet varied dramatically based on location and prey availability. Some populations feasted heavily on large marine mammals, while others like those in ancient German waters preferred smaller prey, including fish and even other sharks.

“Megalodon was an ecologically versatile generalist,” explains geoscientist Jeremy McCormack. “It wasn’t just a whale killer it was an opportunistic feeder, capable of hunting at multiple levels of the food chain”.

Zinc Isotopes: The Hidden Clues in Megalodon’s Teeth

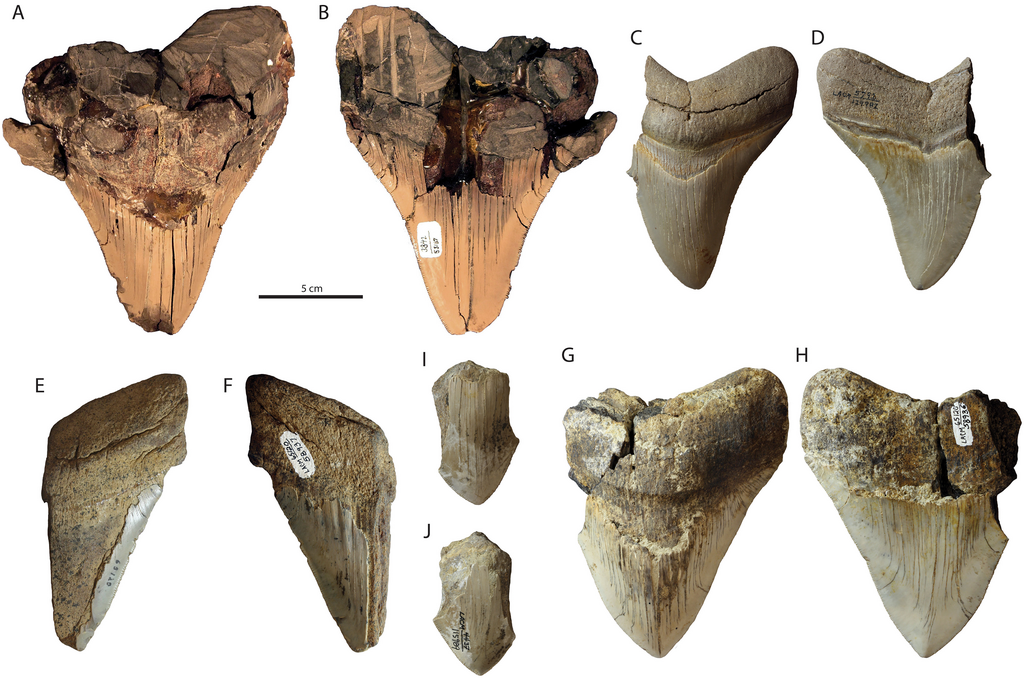

Megalodon’s cartilaginous skeleton is hardly ever fossilized, thus teeth provide the main window into its biology. But unlike conventional bite-mark study, which only provides images of specific meals, zinc isotopes expose long-term dietary trends.

Here’s how it works:

- Lighter zinc isotopes (zinc-64) accumulate in top predators.

- Heavier isotopes (zinc-66) dominate in herbivores and smaller fish.

By comparing megalodon teeth to those of modern sharks, scientists discovered that megalodon’s zinc ratios matched those of apex predators but with a twist. Unlike modern great whites, which show consistent isotopic signatures, megalodon’s teeth displayed wild variations, indicating a diet that shifted based on prey availability.

“This suggests megalodon wasn’t locked into one feeding strategy,” says palaeontology Kenshu Shimada. “It could switch from hunting whales to scavenging smaller prey when necessary”.

Cannibalism and the Shark-Eat-Shark World of the Ancient Oceans

Perhaps the most startling revelation? Megalodon didn’t just eat other species, it likely ate its own kind.

Fossil records show that newborn megalodons, measuring about 6 feet (1.8 meters) long, were vulnerable to predation possibly even by adult megalodons 6. This behavior, known as intra-species predation, is common in modern sharks but adds a brutal layer to megalodon’s already fearsome reputation.

“When you’re at the top of the food chain, you don’t discriminate,” says Emma Kast, a paleoecologist who studies ancient marine food webs. “Megalodon’s trophic level was so high that it had to consume other apex predators including its own juveniles”.

The Great White Shark Connection: Did Competition Kill Megalodon?

Around 3.6 million years ago, megalodon vanished and scientists now suspect that competition with great white sharks played a key role.

Zinc isotope analysis reveals that by the Pliocene epoch, great whites and megalodons were hunting the same prey. But while megalodon needed massive amounts of food to sustain its 50-ton body, great whites, smaller and more energy-efficient, could thrive on less.

“Resource competition was likely a death sentence for megalodon,” says Shimada. “When the oceans cooled and prey became scarce, the smaller, more adaptable great whites outlasted them”.

Climate Change: The Final Nail in the Coffin

Megalodon’s extinction wasn’t just about competition, it was also a story of climate disaster.

As Earth entered a cooling phase, ice caps expanded, sea levels dropped, and the warm coastal nurseries where megalodon pups thrived vanished. At the same time, many whale species, megalodon’s primary prey migrated to colder waters or went extinct.

“Megalodon was adapted to a world that no longer existed,” explains McCormack. “Its size, once an advantage, became a liability”.

Could Megalodon Still Be Alive? The Cold, Hard Truth

Despite sensational documentaries and cryptozoology claims, the answer is a definitive no.

“If megalodon still existed, we’d know,” says Emma Bernard, curator of the Natural History Museum’s fossil fish collection. “An animal that big would leave behind thousands of teeth and bite marks on whales. And as a warm-water species, it couldn’t survive in the deep ocean’s cold abyss”.

Conclusion: A Predator Unlike Any Other

Megalodon wasn’t just a bigger version of today’s great white it was a uniquely adaptable superpredator that ruled the oceans for 20 million years. Its diet was more varied, its behavior more ruthless, and its extinction more complex than we ever imagined.

And while it’s gone, its legacy lives on not just in fossilized teeth, but in the lessons it teaches us about evolution, competition, and the fragile balance of Earth’s ecosystems.

As Shimada puts it: “Even the mightiest predators are not immune to extinction.”

Sources:

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.