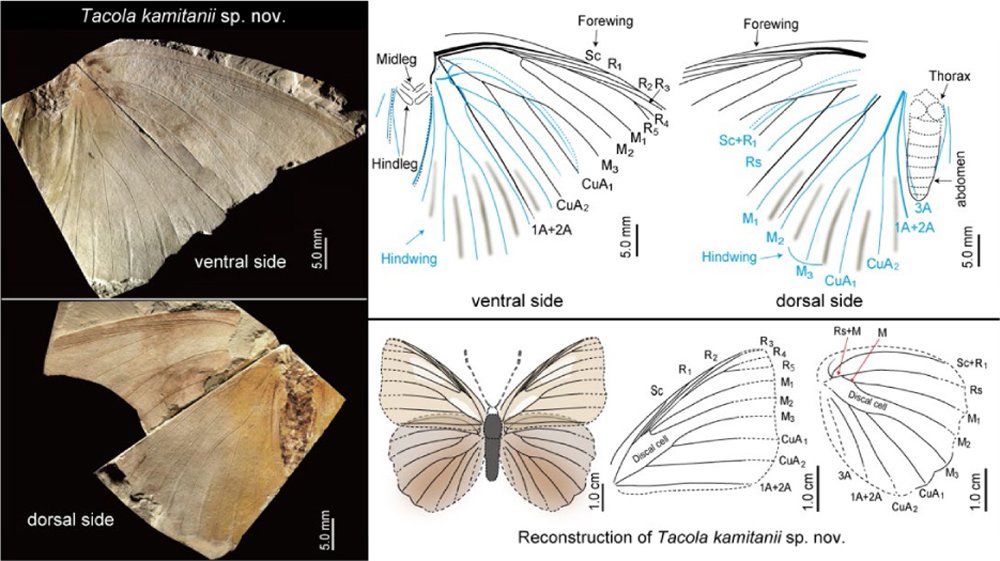

For decades, an enigmatic fossil sat quietly in Japan’s Museum of Unique Insect Fossils its origins a mystery. Discovered in 1988 in Hyogo Prefecture, the delicate imprint of a butterfly’s wing and body was labeled merely as an “extremely rare” specimen. Now, over thirty years later, researchers have unlocked its secret: it is the fossil of an as-yet unrecognized extinct species, the first butterfly fossil to be recorded from the Pleistocene period.

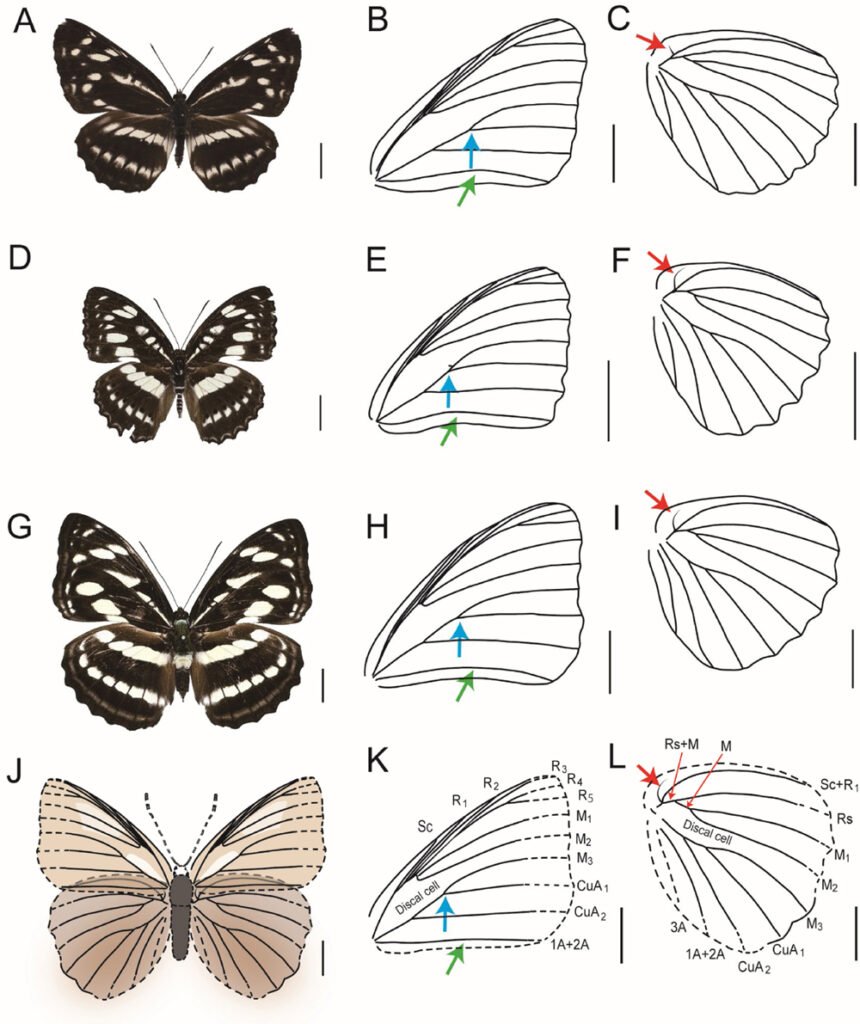

Released May 2 in Paleontological Research, the study reveals Tacola kamitanii, a butterfly that soared above ancient Japan 2.6 million to 1.8 million years ago. Named for fossil hunter Kiyoshi Kamitani, the remarkable find supersedes our understanding of butterfly evolution and extinction and raises intriguing questions about the fate of insects in a changing world.

A Fossil Hidden in Plain Sight

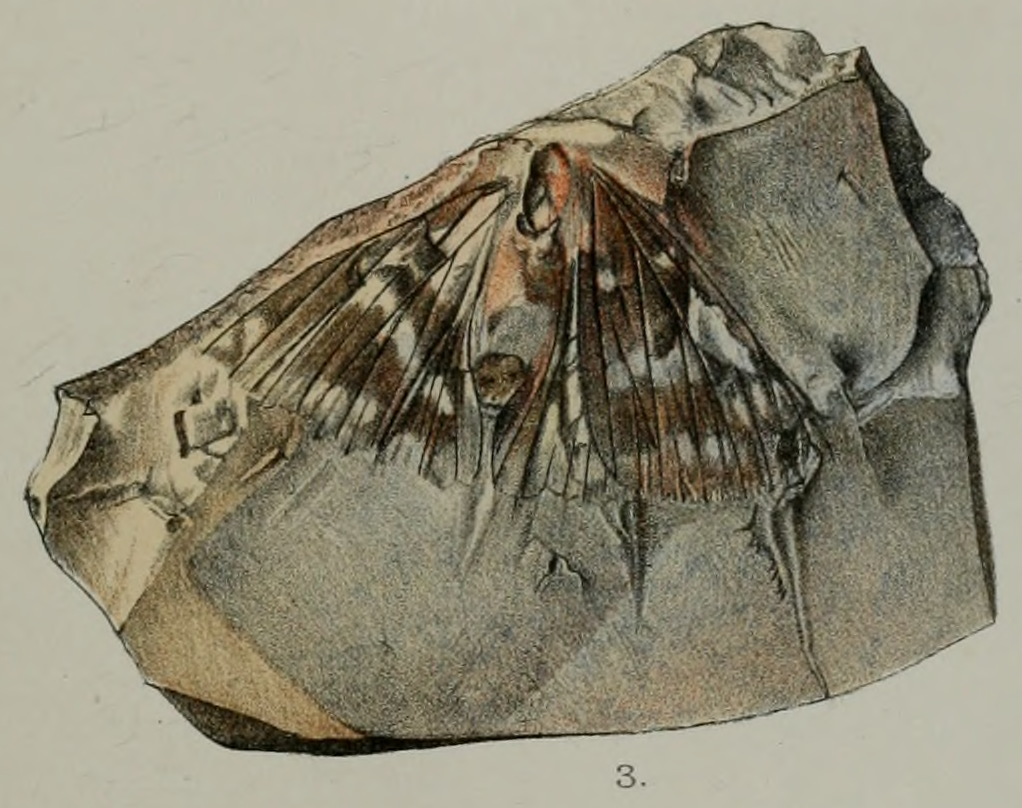

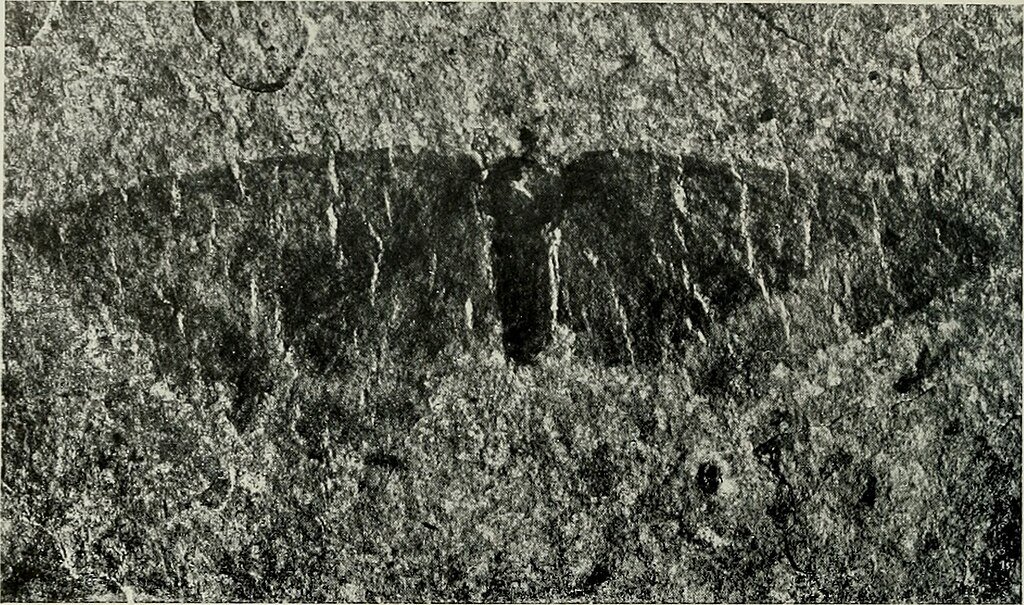

The fossil’s journey from obscurity to scientific revolution began in the small town of Shin’onsen, nestled in northeastern Hyogo Prefecture. Unearthed in 1988, the specimen was preserved in fine-grained sediment, a stroke of luck, given how rarely butterflies fossilize. Unlike beetles or dragonflies, whose tough exoskeletons endure time, butterflies are fragile. Their wings and lightweight bodies disintegrate easily, leaving behind almost no trace.

“Butterfly fossils are extremely rare,” the researchers emphasized in their study. “Their delicate structure and buoyant nature make them far less likely to be preserved than other insects.” This makes Tacola kamitanii not just a new species, but a near-miraculous snapshot of prehistoric life.

A Giant Among Butterflies

One of the most impressive aspects of Tacola kamitanii is how big it was. Its estimated wingspan of almost 9 cm (3.5 inches) made it much bigger than most butterflies today. To put this into perspective, the common monarch butterfly of today measures approximately 10 cm (4 inches) on average, so this prehistoric species was a real giant.

The fossil’s thick abdomen and robust body structure suggest it was a female, possibly adapted for egg-laying in a climate that was rapidly cooling. “This was a butterfly that thrived during a period of dramatic environmental change,” explains lead researcher Hiroaki Aiba. “Its size may have been an evolutionary response to shifting temperatures.”

A Window Into the Pleistocene World

The Early Pleistocene epoch was a time of transition. As global temperatures dipped, Japan’s lush subtropical forests gave way to cooler woodlands. Tacola kamitanii likely lived in warm-to-mild zones before vanishing as the climate grew harsher.

“This discovery extends the known range of the Tacola genus,” says co-author Yui Takahashi. “It suggests these butterflies were once widespread across Southeast and East Asia before retreating or disappearing as the ice ages advanced.”

A Missing Link in Butterfly Evolution

Tacola kamitanii belongs to the Limenitidini subfamily, a group that includes modern admirals and viceroys. Yet, until now, no fossil evidence of this lineage had ever been formally identified.

“This is the first named fossil from the Limenitidini subfamily,” the researchers note. “It fills a crucial gap in our understanding of how these butterflies diversified and why some lineages died out while others survived.”

Why Did This Butterfly Go Extinct?

The exact cause of the disappearance of Tacola kamitanii is unclear, but one suspect with a strong motive is climate change. During the Pleistocene epoch there were recurrent glacial cycles with the ice sheets advancing and retreating over the Northern Hemisphere. To a warmth-accustomed species, the variations may have been catastrophic.

“Japan’s islands were undergoing significant ecological upheaval,” says Kotaro Saito, another study co-author. “Some species adapted. Others, like Tacola kamitanii, may have simply run out of time.”

What This Discovery Means for Science

Aside from its uniqueness, Tacola kamitanii provides a sobering reminder: even insects as hardy as butterflies are susceptible to environmental changes. With contemporary climate change speeding up, scientists predict that we might be seeing another wave of extinctions this time, courtesy of human hands.

“Fossils like this remind us that biodiversity is fragile,” says Aiba. “Understanding past extinctions helps us protect the species we have left.”

For now, Tacola kamitanii stands as a ghost of warmer worlds a whisper from an era when giant butterflies danced over Japan’s ancient forests, only to vanish into the shadows of deep time.

Sources :

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.