In the misty crags of the Canadian Rockies, a set of ancient footprints has surfaced, each one a whisper from a creature that last walked the Earth 100 million years ago. But these are no ordinary dinosaur tracks. They’re the first of their kind, offering unprecedented insight into a club-tailed tank of a dinosaur never before confirmed in this part of the world.

Three Toes, One Tail Club: A Paleontological Puzzle

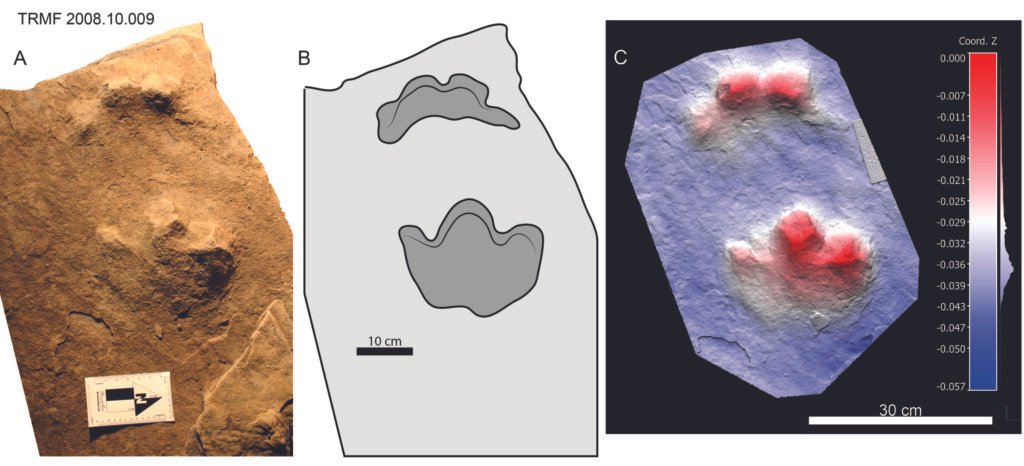

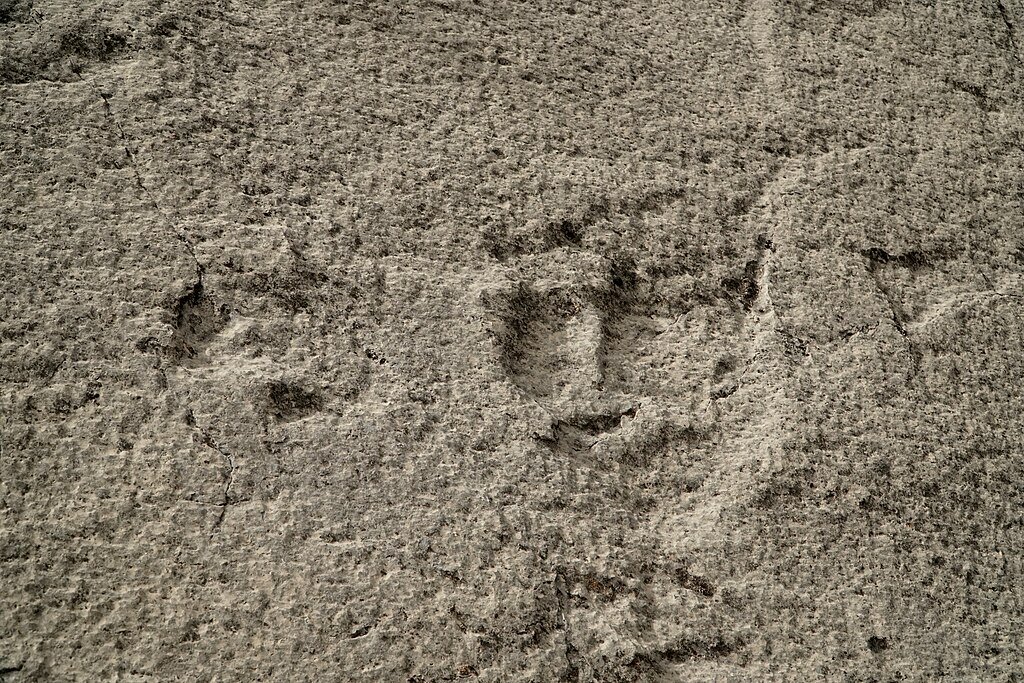

For decades, paleontologists in North America have catalogued countless footprints left by nodosaurids, a type of armored dinosaur with flexible tails and four-toed feet. But a set of strange, three-toed tracks discovered in British Columbia’s Peace Region raised eyebrows and then, questions.

These tridactyl prints didn’t match anything on record.

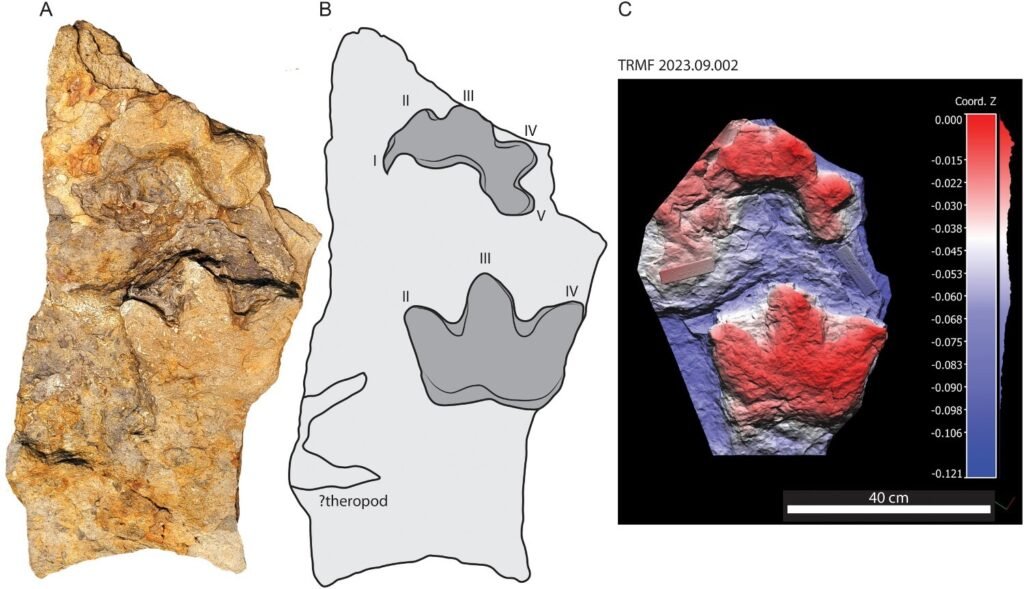

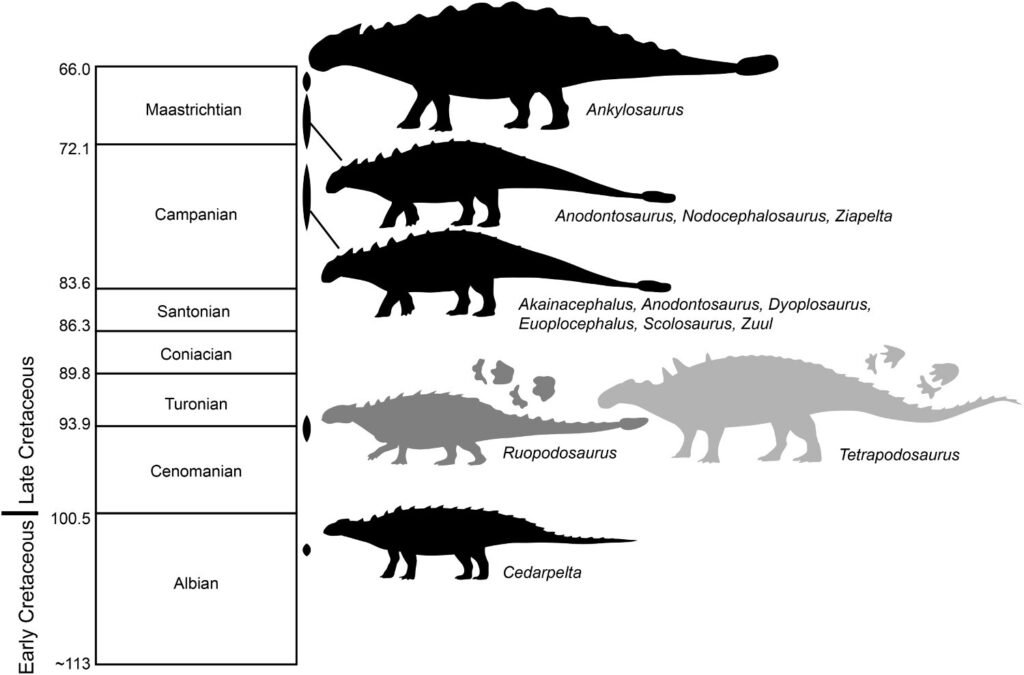

Now, after years of study and a multidisciplinary collaboration, researchers have given these footprints a name: Ruopodosaurus clava, or “tumbled-down lizard with a club.” The species, identified not by bones but by its tracks, likely belonged to the ankylosaurid branch of armored dinosaurs infamous for wielding massive, bony tail clubs and sporting only three toes per foot.

Unearthed in the Clouds: Discoveries at Tumbler Ridge

The footprints were found at two sites, Tumbler Ridge in British Columbia and northwestern Alberta amid the foggy foothills of the Canadian Rockies. The sites, already rich in paleontological history, became focal points for a team led by Dr. Victoria Arbour of the Royal BC Museum and Dr. Charles Helm of the Tumbler Ridge Museum.

While the Peace Region has long yielded classic Tetrapodosaurus borealis tracks, which feature four toes, these new tracks challenged the status quo. They were distinct, deeply impressed, and consistently three-toed an anatomical trait exclusive to ankylosaurids.

“We now have clear ichnological evidence that ankylosaurids, not just nodosaurids, were stomping around North America far earlier than their bones ever told us,” said Dr. Arbour.

Why No Bones? Filling a 16-Million-Year Gap

Here’s the mystery: while ankylosaurid bones are common in later Cretaceous deposits (around 84 to 66 million years ago), there has been a conspicuous absence of fossilized remains dating between 100 and 84 million years ago.

That’s a 16-million-year blank spot until now.

The Ruopodosaurus clava tracks date to the Cenomanian age (roughly 100–94 million years ago), predating any known North American ankylosaurid bones. In doing so, they bridge a major gap in the fossil record and suggest that these tail-clubbed creatures were far more widespread and persistent than once believed.

The Science of Ichnotaxonomy: When Footprints Tell the Tale

In paleontology, identifying a new species based solely on footprints is an extraordinary feat. Known as ichnotaxonomy, this science categorizes species by their tracks rather than skeletal remains a bit like profiling a suspect from a single muddy bootprint.

But in this case, the shape, depth, gait, and toe count of the prints spoke volumes. Unlike the rounded, tetradactyl impressions of Tetrapodosaurus borealis, the tracks of Ruopodosaurus featured pointed toes and a distinct stride pattern. They weren’t just different, they were unmistakably new.

“These are not random anomalies,” said Eamon Drysdale, curator at the Tumbler Ridge Museum. “They represent a unique morphotype consistent across multiple sites and specimens.”

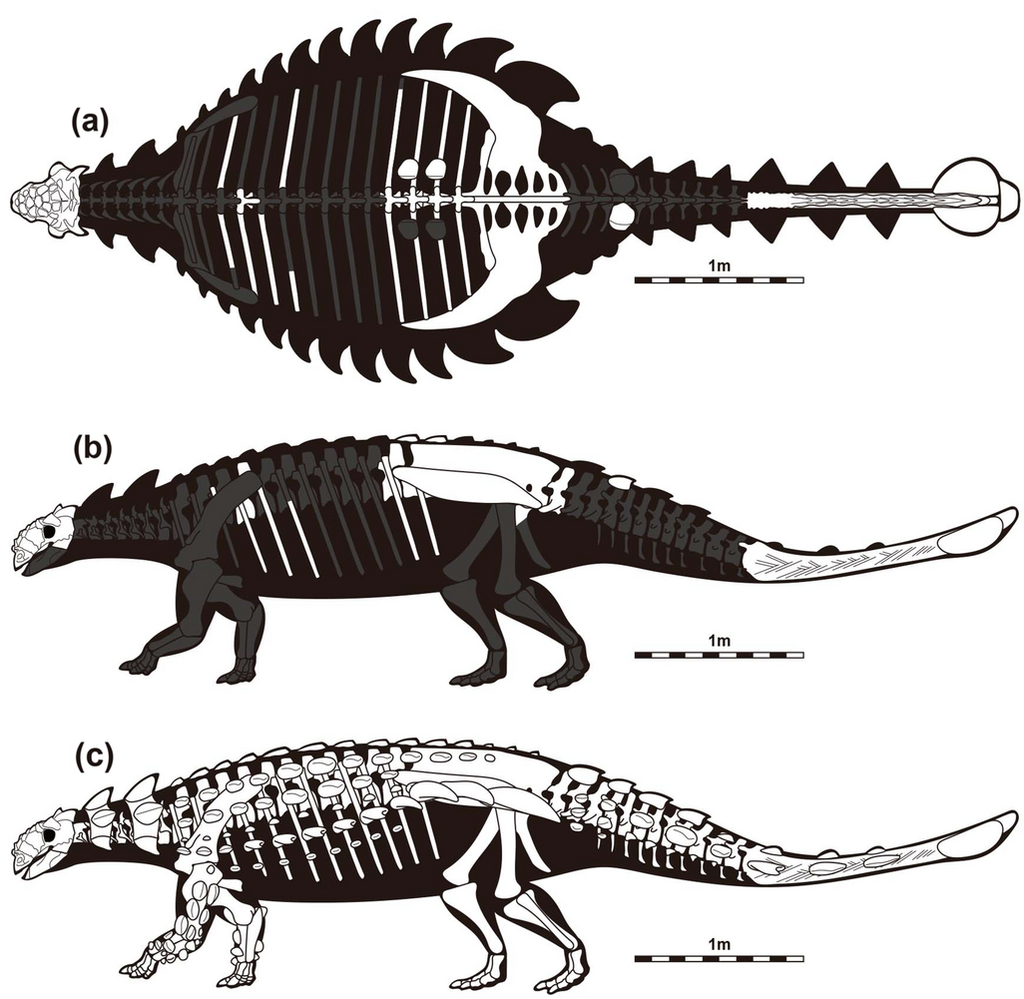

Meet the Monster: What Did Ruopodosaurus Look Like?

We don’t yet have a skeleton to admire, but paleontologists can make educated guesses based on related species. The dinosaur that left these prints was likely 5–6 meters long, sheathed in bony armor, and sported spikes along its flanks. Most distinctively, it probably carried a sledgehammer-like tail club, a weapon for fending off predators.

Think of a medieval war machine with scales, trudging across a floodplain, leaving behind imprints that would one day baffle and delight scientists.

” Ankylosaurus are my favorite dinosaurs to work on,” Arbour told me. “So being able to identify a new kind of trackway right here in British Columbia is thrilling both professionally and personally.”

Two Giants, One Terrain: Coexistence in the Mid-Cretaceous

One of the most fascinating implications of the find is that Ruopodosaurus clava and Tetrapodosaurus borealis appear to have shared the same ecosystems. The tracks from both species were found in the same sediment layers, suggesting they lived side-by-side in the mid-Cretaceous Peace Region.

Why did two similar but distinct armored dinosaurs occupy the same turf? Did they feed on different plants? Roam different elevations? Or were they separated by behaviors we’ll never fully decode?

“This kind of overlap hints at niche partitioning,” explained Roy Rule, geoscientist at the Tumbler Ridge UNESCO Global Geopark. “It’s a rare window into how multiple armored species might have coexisted.”

Footprints in Time: More Than Just Dinosaur Clues

The discovery of Ruopodosaurus serves as a reminder that secrets can still be found beneath mossy stones, crumbling cliffs, and along long-forgotten trails. These fossilized steps, preserved for eons in ancient mudflats, are more than just interesting; they are records of movement, behavior, and life itself.

With more exploration taking place in British Columbia and Alberta, scientists hope that these prints are just the beginning. Maybe bones will follow. Perhaps another species will appear from the shadows. For the time being, these tracks are the literal footprints of a long-forgotten lineage, rediscovered through a combination of curiosity, persistence, and scientific research.

Sources:

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.