Every culture has a monster story, but many of those legends began with something you could pick up, turn in your hand, and misread – a bone. For centuries, miners, shepherds, and sailors stumbled onto fossilized remains and tried to make sense of them without the tools of modern science. The result was a gallery of marvels: one-eyed giants, gold-guarding griffins, city-slaying dragons, and sea serpents big enough to swallow ships. Today, high-resolution scans, chemical fingerprinting, and ancient DNA peel back those stories to reveal the real animals behind the myths. What follows is a tour of nine remarkable bones and the very human tales they sparked.

The Hidden Clues

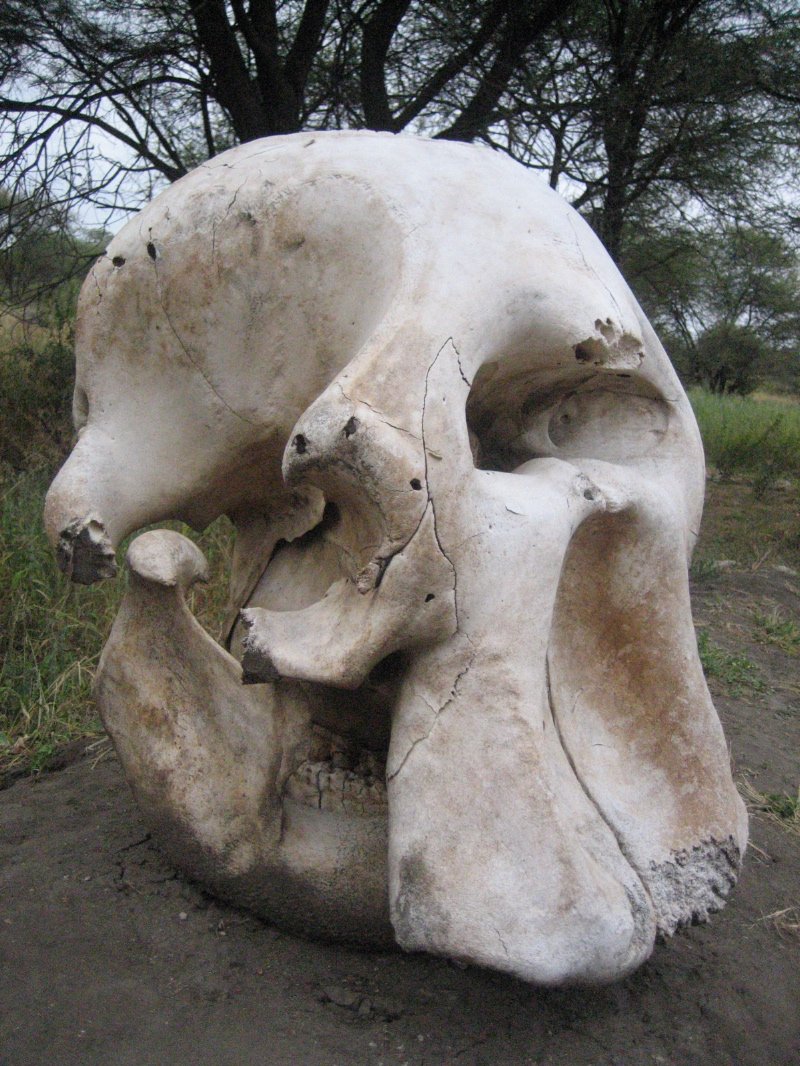

What if the world’s most famous monsters began with a single skull found on a sunlit hillside? On Mediterranean islands, fossil dwarf elephant skulls show a huge central opening that once held a trunk, not an eye, yet to herders and sailors that void looked like the socket of a Cyclops. In classical Greece, temples proudly displayed colossal “hero” bones that awed pilgrims; we now recognize many as Ice Age mammoth or mastodon remains weathered out of cliffs and caves.

These finds weren’t fringe curiosities – they were conversation starters that shaped origin stories, borders, and faith. Without microscopes or geology, people used the best tool they had: imagination guided by experience at sea and on land. Those guesses often missed the target, but they carried a kernel of truth that modern research can finally measure.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

Across the Gobi Desert, nomads and traders encountered beaked, frilled skulls eroding from ocher slopes; the compact, parrot-like jaws and shielded necks of Protoceratops looked uncannily like a lion-bird hybrid guarding its nest. That image traveled along trade routes as the griffin, a vigilant watcher placed beside hoards of gold, mapping fossil beds onto maps of wealth and fear. Meanwhile in China, villagers unearthed large fossil bones and sold them in apothecaries as “dragon bones,” ground to powder for traditional remedies and carefully labeled by province and effect.

Archaeologists and paleontologists can trace these marketplaces of myth in ledgers and mine tailings, then test the remnants today. Under laboratory lights, that “dragon bone” powder often turns out to be dinosaur or mammal fossil, its minerals preserving microscopic structures that still tell a species story. The route from talisman to specimen is the backbone of science itself.

Cities That Found Their Dragons

In the heart of Europe, two cities literally built their identities on a skull. Klagenfurt’s famous dragon icon grew after a massive, horned skull – now known as woolly rhinoceros – was dug from a nearby gravel pit and exhibited as proof of a slain monster; artists copied its contours for fountains and crests. Not far away, Ljubljana celebrated its own dragon, though its symbol primarily derives from Greek mythology rather than fossil discoveries and was paraded as evidence that legends walk beneath the hills.

To a mason or a magistrate in the 1500s or 1600s, a rhinoceros didn’t fit any living European creature, but it neatly matched a dragon described in local lore. When those bones moved from a chapel or a city hall into museum drawers, the dragon didn’t vanish; it evolved into a civic story about deep time, geology, and how people read landscapes long before radiocarbon clocks.

Across the Atlantic: America’s Giant Problem

On the floodplains of Kentucky and Ohio, hunters and surveyors pulled up tusks and molars the size of bricks, and a new American mystery was born: the incognitum, a vanished beast taken to be the remains of a giant or a monstrous elephant. Debates raged over whether such creatures still roamed the unexplored West, or whether extinction – an unsettling idea at the time – was even possible on a bountiful continent. Naturalists eventually recognized the pattern of ridged teeth and curved tusks as mastodon and mammoth, Ice Age proboscideans that had thrived and disappeared long before European settlers arrived.

The first time I held a mammoth molar in a museum drawer, its weight surprised me; it felt like a chunk of a paved road, dense and humanly impossible to miss. That heaviness explains why communities built stories around the bones: they were too substantial to ignore and too strange to place. Science offered an answer, but only after the myths had done their work of keeping the fossils in public view.

Monsters of the Deep

In the 1760s, quarry workers near Maastricht revealed a colossal skull with conical teeth and paddle-ready jaws; scholars argued whether it was a fish, a crocodile, or something altogether new. That animal became the mosasaur, an apex marine reptile whose remains fueled arguments about biblical leviathans and reshaped ideas about Earth’s past oceans. A few decades later along England’s Jurassic Coast, cliff-fall carcasses of ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs brought the sea to life in stone, and seafarers folded those images into every reported serpent and long-necked swimmer on the horizon.

These weren’t simple misreads – they were mirrors held up to risky trades and hazardous coasts. When the ocean itself was a workplace, a skeleton with flippers and teeth could be evidence of what waited beyond the headland. Today’s reconstructions, built from CT scans and sediment chemistry, make those creatures vivid without the terror.

The Hidden Clues, Revisited

Return to the Cyclops skull and the temple “giants,” and the pattern sharpens: a single anatomical oddity can steer a whole legend. The round void at the front of an elephant skull, the sweeping frill of a Protoceratops, the massive nasal bones of a woolly rhinoceros – each feature begs for a familiar explanation, and myth supplies one quickly. Add trade, faith, or politics, and the explanation hardens into shared belief, carved into stone and law.

Science doesn’t erase those beliefs so much as translate them. When field teams map a site and date the sediments, they are, in a sense, annotating the margins of an old story with new notes. The bones haven’t changed, but our questions have grown sharper.

Why It Matters

Understanding how bones become myths shows how people reason under uncertainty, a skill that still shapes debates about health, climate, and technology. Folklore is fast, sticky, and emotionally satisfying; stratigraphy and spectroscopy are slow, precise, and demand patience. Comparing the two reveals where our minds leap ahead and where data asks us to wait.

There’s another payoff: fossils mislabeled as charms or relics have survived because communities valued them, even for the wrong reasons. When those same objects enter a lab, they carry centuries of human context along with their biological signals. That coupling – culture plus chemistry – makes the science richer and the history more honest.

The Future Landscape

New tools are turning myth-bones into high-resolution datasets. Collagen fingerprinting can identify fragmentary fossils to family, ancient DNA and proteomics can tease out relationships, and micro-CT reveals growth lines, tooth wear, and healed fractures invisible to the eye. Portable XRF scanners let researchers analyze in the field without grinding a speck of the specimen away.

Big challenges remain: provenance gaps from centuries-old collections, illicit trade in fossils repackaged as curios, and the ethics of excavation on Indigenous lands. Expect more partnerships that blend museum archives, local knowledge, and open databases so any fragment – no matter how myth-soaked – can be traced and tested. As those networks grow, fewer bones will be stranded in stories alone.

Conclusion

Start close to home: visit a regional museum, read the labels, and notice how many famous fossils began as farm finds or quarry surprises. If you hike or beachcomb, learn your local fossil laws and report significant finds rather than pocketing them; a quick photo with a GPS pin can be the difference between a rumor and a record. Skip purchasing “dragon bone” powders or anonymous fossil trinkets online, where provenance collapses and science loses track.

Support the patient work that turns myths into knowledge – field schools, community collections, and open-access archives that preserve both the bones and the stories attached to them. The next time a spectacular skeleton rolls out of a cliff face, you’ll recognize the moment for what it is: a legend in mid-transformation. Did you expect that?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.