Deep beneath American soil lies a hidden world where evolution operates by entirely different rules. These subterranean realms harbor creatures so specialized that they’ve transformed into living fossils, adapted to eternal darkness and surviving on chemical processes unknown to surface dwellers.

What makes these caves truly extraordinary isn’t just their geological magnificence, but the isolated ecosystems thriving within them. Each cave system acts as its own evolutionary laboratory, where species have been cut off from the surface world for millions of years, developing unique adaptations that boggle the mind of even seasoned biologists.

Mammoth Cave System, Kentucky

Hidden beneath the rolling hills of Kentucky lies the world’s longest known cave system. The Mammoth Cave System is the type locality for 33 cave-limited species. The exceptional diversity at Mammoth Cave is likely related to several factors, such as the high dispersal potential of cave fauna associated with expansive karst exposures, high surface productivity, and a long history of exploration and study.

Our list of cave-limited fauna totals 49 species, with 32 troglobionts and 17 stygobionts. Seven species are endemic to the Mammoth Cave System and other small caves in Mammoth Cave National Park. The system serves as a biological sanctuary where creatures like blind beetles and eyeless cave fish have thrived in perpetual darkness for millennia.

Lechuguilla Cave, New Mexico

Descending over 1,600 feet into the earth, Lechuguilla Cave represents one of America’s most pristine subterranean worlds. Rare chemolithoautotrophic bacteria are believed to occur in the cave. These bacteria feed on the sulfur, iron, and manganese minerals and may assist in enlarging the cave and determining the shapes of unusual speleothems.

Research at Lechuguilla Cave (Carlsbad Caverns National Park) and elsewhere is revealing that microbes found there might produce chemical agents that could be developed into new medications that could be used as antibiotics or even cancer treatments for people. Many microbes that are found only in caves are considered extremophiles, because they live under extreme environmental conditions such as limited food sources, live in super cold or super-hot temperatures, or even in areas with very acidic water.

Edwards Aquifer Caves, Texas

With 91 described stygobite species and at least another 14 awaiting taxonomic description, the subterranean aquatic fauna of Texas is globally renowned. The Edwards Aquifer species diversity ranks among the highest recorded for any aquifer worldwide. This underground river system harbors an astonishing variety of endemic species.

Ezell’s Cave NNL in south-central Texas is home to the Texas blind salamander (Eurycea [=Typhlomolge] rathbuni). This endangered species is found only within water-filled caves of the Edwards Aquifer, a geographically limited area near San Marcos. The salamander’s bright red external gills and ghostly pale appearance make it one of the most distinctive cave creatures in North America.

Wind Cave, South Dakota

While famous for its calcite formations and atmospheric pressure differentials, Wind Cave also shelters unique biological communities. The cave’s intricate maze passages create distinct microenvironments where specialized invertebrates have evolved in isolation. These communities demonstrate how even slight environmental differences can drive evolutionary divergence.

The cave’s seasonal air circulation patterns create varying humidity zones that support different assemblages of cave-adapted species. Some chambers remain consistently moist while others experience dramatic seasonal changes, leading to remarkable niche specialization among resident organisms.

Ruby Falls Cave, Tennessee

Deep within Lookout Mountain, Ruby Falls Cave provides habitat for several endemic species adapted to its unique hydrogeological conditions. The cave’s underground waterfall creates a distinct ecosystem where humidity levels and nutrient availability differ dramatically from typical dry cave environments.

The constant mist from the waterfall supports specialized bacterial mats that form the foundation of a unique food web. Cave-adapted arthropods have evolved to exploit this unusual resource, developing feeding strategies found nowhere else on Earth.

Oregon Caves, Oregon

Known as the “Marble Halls of Oregon,” this cave system harbors Pacific Northwest endemic species that have been isolated since the last ice age. A lot of the organisms that are stuck in caves are remnants from the last Ice Age. As the glaciers were receding, these animals were left with a quickly changing habitat and landscape. Some of them found shelter in caves and they just stayed there and evolved over thousands of years.

The cave’s unique position in the Siskiyou Mountains creates a refuge where ancient lineages persist. Species here show remarkable convergent evolution with cave fauna from other continents, yet maintain distinct genetic signatures reflecting their isolated Pacific Northwest origins.

Jewel Cave, South Dakota

the world’s third-longest cave system contains an extraordinary diversity of cave-adapted species living within its crystalline chambers. The cave’s extensive network of narrow passages creates thousands of isolated pockets where evolution proceeds independently.

Many of these creatures display extreme specialization to their specific chamber environments. Some have evolved to feed exclusively on the unique mineral deposits found in particular cave sections, while others have adapted their life cycles to match the cave’s subtle seasonal temperature fluctuations.

Carlsbad Caverns, New Mexico

Beyond its famous bat colony, Carlsbad Caverns supports a diverse community of obligate cave dwellers. The cave’s multiple levels and varied chemistry create distinct ecological zones, each supporting its own endemic fauna.

The deeper sections of the cave harbor species that have never been exposed to surface conditions. These organisms have evolved such extreme adaptations to cave life that they would perish if brought to the surface, making them true prisoners of their subterranean world.

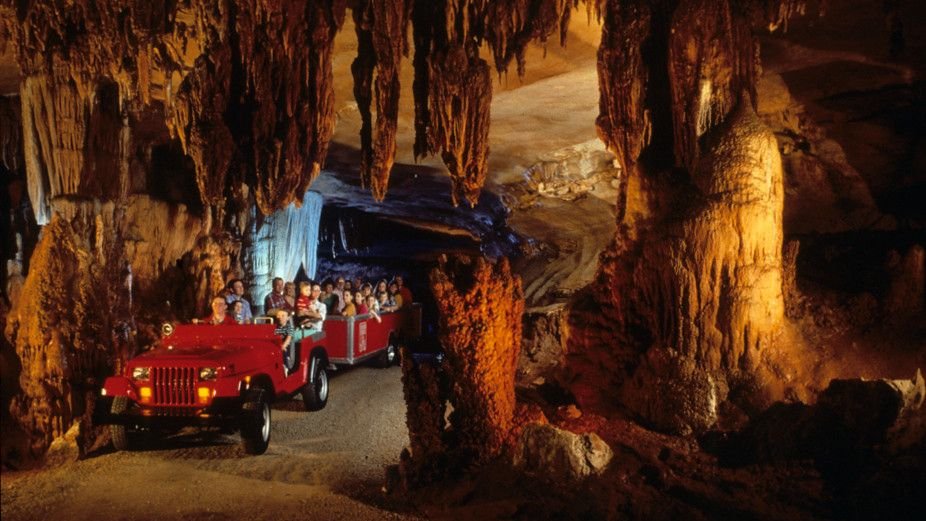

Fantastic Caverns, Missouri

Missouri’s only ride-through cave also serves as home to numerous endemic species adapted to the Ozark karst environment. A related species, the grotto (or Ozark blind) salamander (Eurycea spelaea) can be found in the Tumbling Creek Cave NNL in southern Missouri. An unusual characteristic of this cave critter is that that they are fully sighted at the larva stage, however they lose both sight and pigmentation after they metamorph

The cave’s connection to the Springfield Plateau aquifer creates a unique habitat where aquatic and terrestrial cave species interact in complex ways. This intersection supports one of the most diverse cave communities in the Midwest, with species showing remarkable adaptations to both aquatic and terrestrial cave environments.

The Hidden Power of Seasonal Turnover

In the fall, the surface waters cool until they are as dense as the bottom waters. With the help of the wind, the lake can mix and this is called “fall turnover.” Oxygen from the surface mixes with the bottom. Nutrients and decomposing organic matter from the bottom is mixed up and throughout the lake. This process fundamentally shapes cave ecosystem dynamics in ways scientists are only beginning to understand.

In the fall and spring, parts of Lake Champlain undergo a mixing called “lake turnover.” During turnover, oxygenated surface waters cool and sink, supplying oxygen to the bottom of the lake, and water from the deeper hypolimnion layer rises to the surface. Seasonal mixing is an important process that replenishes oxygen and distributes nutrients throughout the lake. In cave systems connected to surface waters, this mixing dramatically affects the availability of dissolved oxygen and nutrients that filter into underground ecosystems.

Conclusion

These remarkable cave systems represent living laboratories where evolution operates under conditions radically different from the surface world. Each cave tells a unique story of adaptation, isolation, and survival in environments that challenge our understanding of life itself.

Most cave species have small populations, restricted ranges, and low rates of reproduction. Even though individual species population’s may be limited, cave critters can be found all over the world, including in caves on both publicly and privately-owned lands. The fragility of these ecosystems makes their conservation critical, as many endemic species exist nowhere else on Earth.

What fascinates you more about these hidden worlds – their ancient origins or their potential to unlock medical breakthroughs? Share your thoughts with us in the comments below.

Hi, I’m Andrew, and I come from India. Experienced content specialist with a passion for writing. My forte includes health and wellness, Travel, Animals, and Nature. A nature nomad, I am obsessed with mountains and love high-altitude trekking. I have been on several Himalayan treks in India including the Everest Base Camp in Nepal, a profound experience.