Why does the universe look so orderly when, underneath, it seems governed by chaos and mystery? Astronomers can map distant galaxies and weigh black holes, yet some of the biggest questions about reality itself remain maddeningly open. Over the last few decades, powerful telescopes, gravitational-wave detectors, and particle colliders have turned cosmology into a precision science, but they’ve also exposed cracks in what we thought we knew. Each new mission, from the James Webb Space Telescope to probes at the edge of our solar system, answers one question and raises three more. What we’re left with is a portrait of a universe that feels familiar on the surface, but gets weirder, darker, and harder to explain the deeper we look.

The Hidden Clues in the Cosmic Microwave Background

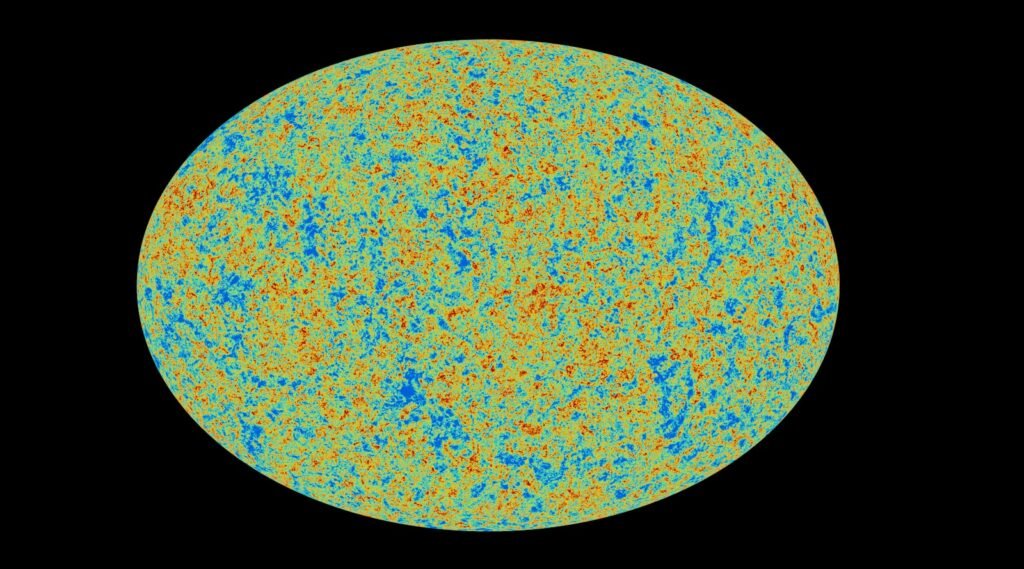

Imagine opening an old photograph of the universe as a baby and realizing there are fingerprints on the corners that nobody can explain. That is essentially what cosmologists see in the cosmic microwave background, the faint afterglow of the Big Bang that satellites like Planck and WMAP have mapped in exquisite detail. The overall pattern looks like a triumph for modern cosmology: tiny temperature ripples that match predictions of the Big Bang and cosmic inflation to impressive precision. But when scientists zoom out to the largest scales, they find strange alignments and asymmetries that stubbornly refuse to fit the clean, random picture. One famous oddity, sometimes nicknamed the “axis of evil,” hints that temperature variations in completely different parts of the sky might line up more than they should. If these features are real and not just cosmic coincidence, they could mean our standard model of the universe is missing some hidden ingredient or early-universe twist.

For now, cosmologists live with a kind of productive discomfort: the map mostly works, but the weird corners nag at them. Some suggest that these anomalies could be statistical flukes, the cosmological equivalent of seeing faces in clouds when you stare long enough. Others wonder if they’re subtle traces of exotic physics in the first fractions of a second after the Big Bang, when space itself was inflating faster than light. Testing that idea will require even more precise sky surveys and future satellites that can measure polarization patterns in the cosmic microwave background with almost absurd sensitivity. Until then, those faint, cold photons carry secrets about our origins that we can see, but not yet fully interpret.

Dark Matter: The Gravity We Can’t See

Walk outside on a clear night and everything you see – planets, stars, glowing gas – is just the visible tip of a cosmic iceberg. Multiple independent lines of evidence show that most of the matter in the universe is dark, invisible to telescopes, detectable only through the way its gravity tugs on galaxies and bends light. Spiral galaxies rotate so fast that, without an unseen halo of extra mass, their stars should have been flung into space long ago. Massive clusters of galaxies act like gravitational lenses, magnifying and warping the light from objects far behind them in ways that betray vast pools of something that does not shine.

The problem is painfully simple to state: astronomers can measure how much dark matter there seems to be, but particle physicists still have no idea what it actually is. Decades of underground experiments have hunted for hypothetical particles that might occasionally bump into ordinary atoms, and high-energy collisions at facilities like the Large Hadron Collider have probed for hints of new physics, but the detectors remain frustratingly quiet. A few teams have reported intriguing blips and excesses, only for follow-up studies to erase the excitement. Meanwhile, alternative ideas like modified gravity tweak the laws of motion themselves to explain the observations without dark matter, but those theories strain to match the full diversity of cosmic structures. For now, the universe appears to be held together by something we can weigh but not see, name, or put in a textbook.

Dark Energy and the Question of Cosmic Fate

If dark matter is the invisible scaffolding that holds galaxies together, dark energy is the mysterious shove that is prying the universe apart. In the late nineteen-nineties, astronomers studying distant exploding stars expected to find that cosmic expansion was slowing, dragged back by gravity like a ball thrown upward. Instead, they saw the opposite: the expansion of space itself is speeding up. That discovery forced cosmologists to add another unknown component to the universe’s budget, a kind of energy built into the fabric of space that drives acceleration. Roughly about two thirds of the total energy content of the cosmos now falls into this catch-all box called dark energy.

What makes dark energy especially maddening is that almost every explanation creates new puzzles. A simple version, known as the cosmological constant, matches observations reasonably well but clashes horribly with calculations from quantum theory, which predict a vacuum energy many orders of magnitude larger. Other models imagine a slowly changing energy field that fills all of space, but those ideas can be difficult to test and risk running into conflicts with precision measurements of the early universe. Massive ongoing surveys of galaxies and supernovas are trying to track how the expansion rate has changed over billions of years, hoping to spot tiny deviations that might favor one theory over another. Somewhere inside those measurements lies the answer to a very human question that rarely makes the headlines: Will the universe coast gently into a cold, dark future, or are we headed toward something stranger, like a runaway “big rip” that eventually tears apart galaxies, stars, and even atoms?

Black Holes and the Edge of Physics

Black holes are often described as cosmic monsters, but the real horror story is what they do to our laws of physics. On one hand, Einstein’s general relativity describes their gravity perfectly, predicting how they warp spacetime so strongly that not even light can escape. On the other hand, quantum mechanics demands that information about matter can never truly be destroyed. When you combine those principles at the edge of a black hole, especially when it eventually evaporates through a process called Hawking radiation, the equations seem to insist that information is lost forever. That contradiction, known as the black hole information paradox, has haunted theoretical physics for decades.

Recent years have brought creative proposals involving holographic descriptions of spacetime, quantum entanglement woven into the structure of geometry, and complex calculations that hint information may leak out in subtle ways. Still, no one has produced a consensus solution that most physicists are willing to stake their careers on. Observations have added another layer of mystery: real black holes imaged by the Event Horizon Telescope, and ripples in spacetime from black hole collisions detected by LIGO and Virgo, match general relativity to impressive precision. That leaves researchers trying to reconcile a theory that works brilliantly on large scales with a quantum picture that rules the microscopic world. Somewhere near the event horizon, at a boundary we can see but never visit, the two must meet – and for now, they refuse to shake hands.

The Hidden Architecture of the Solar System

Even in our own cosmic backyard, things refuse to line up as neatly as textbooks suggest. Over the last two decades, precise tracking of distant icy worlds beyond Neptune has hinted that some orbits are oddly clustered, as if shepherded by a massive, unseen object far from the Sun. This has fueled speculation about a hypothetical Planet Nine, a giant world perhaps ten times the mass of Earth lurking in the dark outskirts of the solar system. Computer simulations show that such a planet could corral smaller bodies into the patterns astronomers see, adding weight to the idea. But direct searches have yet to reveal anything, despite sensitive surveys scanning huge swaths of sky.

At the same time, scientists keep stumbling on other small, eerie anomalies: strange tilts, unexpected resonances, and Trojan-like swarms of objects that seem to hint at a more complicated past. Some of these features may be leftovers from the solar system’s turbulent youth, when giant planets migrated and flung debris around like a pinball machine. Others may simply be statistical quirks in data that is still patchy and biased toward brighter, closer objects. Upcoming wide-field surveys and deeper infrared scans could finally confirm or kill the Planet Nine hypothesis and uncover whole populations of worlds we currently miss. Until those results arrive, the outer solar system feels less like a finished map and more like a partially explored archipelago, with blank regions and speculative coastlines waiting for a first real look.

The Nature of Time: Arrow, Flow, or Illusion?

We live our lives inside a one-way river of time, so it’s deeply unsettling to realize that the fundamental equations of physics barely care about direction. Whether you run them forward or backward, many of the core laws look essentially the same, which raises a simple but profound question: Why does time seem to have an arrow? One popular explanation points to entropy, the tendency of systems to move from order to disorder, as the driver that marks the difference between past and future. But that just pushes the mystery back a step, because it forces us to ask why the universe began in such a remarkably low-entropy, highly ordered state. If the cosmos started more like a neatly stacked library than a messy teenager’s bedroom, what did the stacking?

Philosophers and physicists sometimes talk past each other here, because the human experience of time – memories, anticipation, the sensation of “now” – is layered over abstract equations in messy ways. Some researchers argue that the flow of time might be an emergent property, like temperature, arising from the collective behavior of many microscopic processes. Others push even further, suggesting that time as we perceive it could be more like a useful illusion, a way our brains organize events in a fundamentally static or block-like universe. For everyday life, these debates change nothing: clocks tick, heartbeats drum, seasons turn. But for cosmology, understanding time’s arrow is central to any complete story of the universe’s origin and eventual fate.

Why It Matters That the Universe Is Still a Mystery

At first glance, these unresolved questions might sound abstract, like puzzles for people who enjoy chalkboards and midnight coffee. But the way we answer them shapes how we see everything from our place in the cosmos to the technologies we build. The hunt for dark matter has already driven detectors to new levels of sensitivity and pushed particle physics to reexamine comfortable assumptions, sometimes exposing weaknesses in theories once thought unassailable. Probing dark energy forces astronomers to map galaxies across vast volumes of space, which in turn improves our understanding of cosmic evolution and the formation of structures that eventually gave rise to stars, planets, and life. Even black hole paradoxes, seemingly remote from daily experience, feed directly into efforts to unify gravity and quantum mechanics into a single framework.

There is also a quieter, more personal reason this all matters: unanswered questions keep science honest and alive. When data refuses to fit theory, it exposes the limits of our current knowledge and prevents us from mistaking elegant mathematics for truth. Historically, some of the biggest leaps in technology and understanding have come from chasing what looked like small discrepancies, from the orbit of Mercury to the spectrum of hydrogen. We do not yet know which of today’s anomalies will crack open a door to new physics and which will fade with better data, but history suggests at least some will transform the way we think. In that sense, the universe’s stubborn mysteries are not failures of science; they are the fuel that keeps it moving.

The Future Landscape of Cosmic Discovery

The next few decades are poised to turn the sky into a living laboratory, and many of today’s mysteries will be squarely in the crosshairs. New observatories are coming online or being planned that will track millions of galaxies, monitor the sky for gravitational waves in different frequency bands, and peer at exoplanets with enough precision to sniff their atmospheres. These tools will not only refine measurements of dark matter and dark energy, they will also reveal subtle patterns – tiny distortions in galaxy shapes, delicate timing shifts in pulsars – that could betray new forces or particles. Closer to home, next-generation surveys of the outer solar system should uncover thousands of new icy bodies and maybe, just maybe, the rumored heavyweight that has so far dodged detection.

Of course, each new instrument also brings fresh complications: mountains of data to sift through, noise to characterize, and the ever-present risk of confirmation bias when everyone wants to see something revolutionary. There are practical challenges too, from funding and international collaboration to the politics of where giant telescopes can be built. Still, the overall trajectory is clear. Our species is wiring itself a more sensitive nervous system that stretches from deep underground labs to satellites at the edge of interplanetary space. What we do with that nervous system – how carefully we listen, how honest we are about what we hear – will determine which of today’s great cosmic questions we actually manage to answer.

How You Can Stay Curious in a Confusing Cosmos

For most of us, the tools to weigh dark matter or map distant galaxies are out of reach, but staying engaged with these questions is surprisingly powerful. One simple step is to follow missions and observatories that make their data and stories public, from space telescopes to planetary probes; many offer free images, explainers, and even opportunities to help classify features through citizen science platforms. Supporting public science institutions, education programs, and local observatories – whether by visiting, donating, or just showing up for a night-sky event – helps keep these big questions in the cultural conversation rather than buried in specialist journals. Sharing accurate, nuanced stories about space on social media, or pushing back gently against sensational but misleading claims, may feel small, yet it shapes how the next generation thinks about the universe.

On a more personal level, you can treat cosmic mysteries as invitations rather than frustrations. When you read that scientists do not yet know what most of the universe is made of, instead of seeing that as a failure, you can see it as a reminder that we are early in the story. That perspective has a humbling, leveling effect: everyone on Earth, no matter their background, is living through the same grand experiment of discovery. Looking up at the night sky with that in mind turns stars from distant pinpricks into active questions waiting for better tools and braver ideas. In a universe that withholds so many of its answers, choosing to keep asking might be the most human act of all.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.