Our solar system looks calm from a backyard telescope, the planets gliding in orderly paths like clockwork. But behind that stillness lies a history closer to a bar fight than a ballet, written in craters, tilted axes, and worlds that never were. Over the past few decades, astronomers have begun piecing together this violent origin story, using everything from Moon rocks to deep-space probes and supercomputer simulations. What they are uncovering is a cosmic crime scene: giant impacts, planetary migrations, shattered worlds, and frozen clues that challenge our old, gentler narratives of how everything formed. As we retrace these catastrophic events, we’re not just indulging in celestial drama – we’re learning why Earth is habitable at all, and what that might mean for planets circling other stars.

The Giant Impact: When A Proto-Planet Slammed Into Earth

The most dramatic chapter in Earth’s early history is written across the face of the Moon. The leading idea is that our Moon formed when a Mars-sized body – often called Theia – smashed into the young Earth more than four billion years ago, vaporizing rock and splashing molten debris into orbit. That debris eventually coalesced into the Moon, while Earth itself was reshaped, its outer layers melted and mixed in the chaos. Evidence for this comes from the eerie chemical resemblance between lunar rocks and Earth’s mantle, suggesting a shared, violently blended origin rather than a captured outsider.

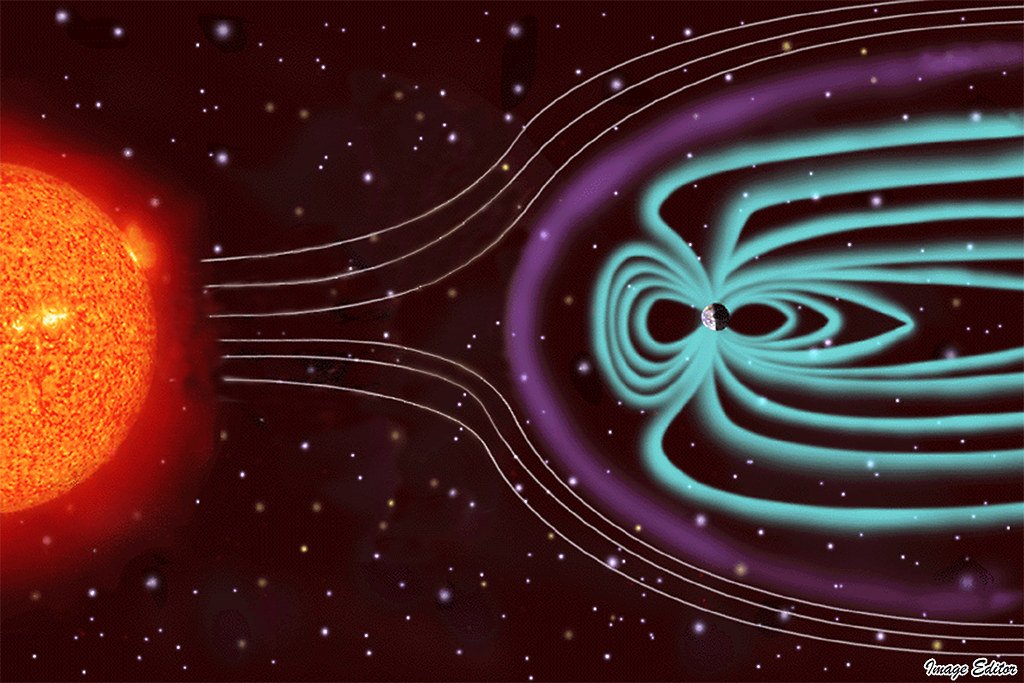

This was not just a spectacular collision; it likely changed everything about Earth’s future. The newly formed Moon stabilized Earth’s tilt, helping to moderate long-term climate swings that might otherwise have been extreme. Tidal interactions slowed our planet’s rapid spin and influenced ocean tides, which many researchers suspect played a role in the chemistry that led to life. It is a strange thought: without that catastrophic impact, our world might never have become a stable, life-friendly planet, and the night sky would be missing its brightest companion.

Planetary Migration: When The Giant Planets Went On The Move

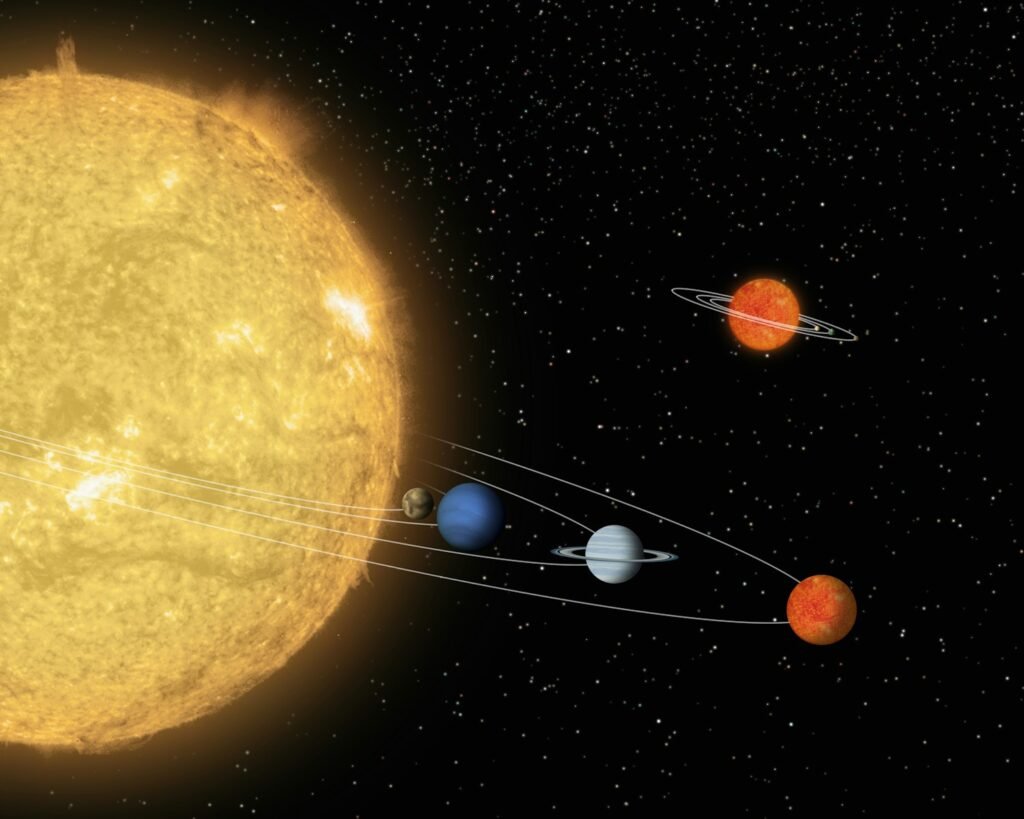

If you imagine the early solar system as neatly arranged from the start, the current science tells a very different story. Models developed over the last two decades suggest that Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune didn’t always live where we see them today. Instead, they likely migrated through the disk of gas and planetesimals, pulled around by gravity and scattering smaller bodies like cosmic shrapnel. In some scenarios, a fifth giant planet once orbited the Sun before being flung out into interstellar space during this gravitational reshuffling.

This wandering had brutal consequences for the smaller objects. As the giants moved, their gravity perturbed vast populations of icy and rocky bodies, ejecting many into deep space and sending others hurtling inward to smash into the inner planets. Some researchers link this migration to a spike in impacts known as the Late Heavy Bombardment, when the Moon and the terrestrial planets were hammered with craters. The result was a solar system that bears little resemblance to its original layout, and a reminder that even planets the size of Jupiter can be nomads for a time.

The Late Heavy Bombardment: A Storm Of Rock And Fire

Look at the Moon through binoculars, and you’re seeing a fossil record of one of the most violent eras our neighborhood ever experienced. Roughly a few hundred million years after the solar system formed, the inner worlds appear to have endured an intense spike in impacts, leaving behind enormous basins like Imbrium and Orientale on the lunar surface. Evidence from radiometric dating of Apollo samples suggests a clustering of impact ages, pointing toward a sustained period of bombardment rather than a slow, steady drizzle of impacts. Earth would have suffered alongside the Moon, but plate tectonics and erosion have mostly erased the scars.

This era was not just destructive; it may have been strangely productive. Frequent, massive impacts could have repeatedly sterilized Earth’s surface, boiling oceans and altering the atmosphere, raising questions about how and when life first gained a foothold. At the same time, those impacts probably delivered volatile materials and stirred up deep-rock chemistry, potentially creating niches where life could persist or restart. Some scientists argue that this planetary-scale pummeling was a harsh filter, shaping which planets in the galaxy might survive long enough, and in the right conditions, to host life. Our own survival through this storm is a reminder of just how narrow that path may have been.

Runaway Accretion: How Dust Turned Into Planets Amid Chaos

Long before giant impacts and bombardments, the violence began at a much smaller scale – literally. Our solar system started as a swirling disk of gas and dust around the newborn Sun, and within that disk, tiny grains collided, stuck, and grew into pebble-sized and then kilometer-scale bodies known as planetesimals. This process was not gentle; collisions were frequent, and many were energetic enough to shatter rather than build. Yet a subset of these bodies grew faster than the rest in a process called runaway accretion, snowballing in mass and gravitational influence.

As these early planetary seeds grew, they began to dominate their orbits, slamming into smaller neighbors or slingshotting them away. Some became the rocky planets we know; others merged into cores that later grabbed thick envelopes of gas and became giants. Many more never made it, ending up as asteroids, comets, or rubble piles scattered throughout the system. In a sense, every world we see today is the survivor of a brutal competition from microscopic dust onward, a fact that makes even a quiet sunset on Earth feel like the end of a very long and violent race.

Catastrophic Collisions: The Shattered World Clues In The Asteroid Belt

The asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter is often described as a junkyard, but it’s more like a graveyard of worlds that almost were. Instead of a single missing planet, current evidence suggests the belt is made of countless fragments from planetesimals that were disrupted in repeated high-speed collisions. Space missions and telescopic surveys have revealed asteroid families – groups of objects sharing similar orbits and compositions – that appear to be the remnants of long-destroyed parent bodies. In some cases, these collisions were energetic enough to completely pulverize objects hundreds of kilometers across.

We also see hints of this violence closer to home. Meteorites found on Earth sometimes carry shock features, melted veins, and mineral changes that only form at extreme pressures, clear signatures of ancient impacts. A few even come from differentiated parent bodies that once had cores and mantles, meaning they were on their way to becoming something more planet-like before being torn apart. These fragments give us a forensic toolkit to reconstruct the solar system’s early demolition derby. When you hold a small meteorite in your hand, you are holding a shard of a world that never survived its violent youth.

Captured And Disrupted Moons: The Strange Histories Of Small Worlds

Not all the drama stayed confined to planets and asteroids; many moons bear scars of violent origins as well. Some of the outer planets’ small, irregular moons likely began life as wandering objects that were captured by gravity in chaotic three-body dances. Others may be the shattered remains of larger moons torn apart by impacts or tidal forces when they ventured too close to their host planets. The odd shapes and unstable orbits of many of these satellites hint at histories full of close calls rather than calm formation in place.

Even the more regular moons show evidence of dramatic internal upheaval driven by this violent environment. For example, intense tidal flexing can fracture crusts, trigger cryovolcanism, and keep subsurface oceans liquid for billions of years. That means the same forces that once threatened to rip small worlds apart might also sustain conditions potentially friendly to life inside them. The solar system’s moons are not quiet side characters; they are survivors, witnesses, and in some cases beneficiaries of the system’s rough upbringing.

Why This Violent Past Matters For Understanding Our Place In The Cosmos

It might be tempting to see these ancient cataclysms as distant curiosities, but they cut to the heart of why we are here at all. For a long time, popular images of planet formation were almost pastoral – dust slowly settling, spheres gently forming, everything cooling into place. The modern picture is closer to a long-running disaster movie: impacts big enough to melt crusts, planets changing orbits, worlds shattered and remade. Recognizing this shift matters, because it reframes habitability not as the default outcome of a calm universe, but as a precarious result of repeated destructive tests.

When astronomers look at exoplanet systems today, they see hot Jupiters skimming dangerously close to their stars, tightly packed super-Earths, and worlds in wildly eccentric orbits. Compared with that cosmic zoo, our own layout looks strangely tidy, and that tidy state probably emerged only after an era of intense chaos. Understanding how our solar system survived its violent youth helps researchers decide which distant systems are most likely to harbor Earth-like planets. It also reminds us that the same impacts and migrations that once looked purely catastrophic may, in the long run, be part of what makes a living world possible.

The Future Landscape: New Telescopes, Sample Returns, And Simulations

We are not done reconstructing this ancient mayhem; in many ways, we are just getting started. New space telescopes and ground-based observatories are refining our view of protoplanetary disks around young stars, effectively letting us spy on other systems as they go through their own violent adolescence. At the same time, missions returning samples from asteroids, the Moon, and eventually Mars are giving scientists exquisitely detailed materials to analyze, down to isotopic fingerprints that can reveal origins and impact histories. Each new sample is like adding a missing page to a crime report written in rock.

Supercomputer simulations are also transforming the field, allowing researchers to run millions of years of planetary dynamics in days, testing which combinations of collisions and migrations can reproduce what we see today. Yet big questions remain: Did a lost giant planet once roam our system? How many near-misses shaped Earth before the impact that formed the Moon? Future missions to the outer solar system, as well as dedicated searches for free-floating planets, could provide crucial clues. As the data grow, our picture of the solar system’s early years may shift again – from very violent to even worse than we imagined.

How You Can Engage With Our Solar System’s Violent Story

You do not need a PhD or a powerful telescope to connect with this unfolding detective story. Simple actions like following space missions, reading mission blogs, or watching live launches help keep public attention – and funding – focused on the exploration that fuels these discoveries. Supporting science museums, planetariums, and local astronomy clubs gives researchers and educators more opportunities to share the latest findings about impacts, migrations, and planetary origins. Even small choices, like choosing science-focused media or encouraging a child’s curiosity about space, ripple outward more than most of us realize.

There are also direct ways to contribute to the research itself. Many citizen science projects invite volunteers to classify craters, track asteroids, or sift through telescope images for unusual objects, turning spare minutes into real data points. And on a more personal level, simply stepping outside to look at the Moon or a bright planet with this violent history in mind can shift your sense of perspective. The calm night sky hides a past full of explosions, broken worlds, and near-misses that ultimately made Earth what it is. Knowing that, how can you look up and not feel just a little more connected to the chaos that forged your home?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.