If you could stand under the night sky thousands of years ago, with no city lights and no smartphone in your hand, what would you see? For many ancient peoples, the sky was not just a backdrop of pretty lights; it was a living map, a calendar, a clock, and sometimes a message from the gods. They watched, measured, counted, and predicted the movements of the stars and planets with a kind of stubborn patience that feels almost alien to our rushed lives today.

What’s shocking is how much they figured out with nothing but sharp eyes, simple tools, and a lot of time. Some civilizations tracked eclipses centuries in advance, aligned massive stone structures to the rising of distant stars, and built entire belief systems around cosmic cycles they could reliably predict. Looking at what they pulled off, it’s hard not to feel a bit humbled every time we casually open a weather app or glance at a digital clock. Let’s dig into five of the most astonishing star‑savvy cultures and see just how far ahead of their time they really were.

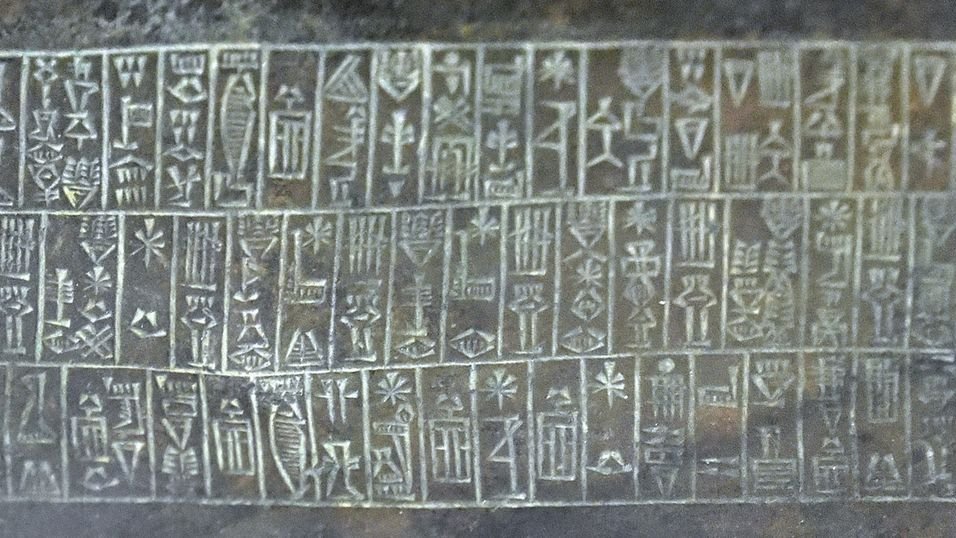

1. The Ancient Babylonians: Masters of Planetary Prediction

The Babylonians, living in Mesopotamia more than two and a half millennia ago, turned the night sky into a kind of cosmic spreadsheet. They did not just stargaze; they logged observations for generations, recording where planets appeared, how fast they moved, and when eclipses darkened the Sun or Moon. Over time, they noticed repeating patterns in these events and began to predict them with surprising accuracy, especially lunar eclipses and the motions of Jupiter, Venus, and Mars.

What stands out is that they were doing something close to mathematical astronomy long before formal science existed. Clay tablets show they used arithmetic techniques, like step‑by‑step calculations of position over time, to forecast where celestial bodies would be on future dates. They connected these predictions to omens and royal decisions, so their sky‑watching had real political weight. Even though they framed their work in religious and astrological language, underneath it was a very real, very systematic approach to tracking the heavens that later influenced Greek and Islamic astronomy.

2. The Ancient Egyptians: Aligning Monuments With the Cosmos

When people think of ancient Egypt, they picture pyramids and temples, but those structures are also silent testimonies to a deep obsession with the sky. Many Egyptian monuments are carefully aligned with cardinal directions and key stars, like Sirius and certain constellations visible at particular seasons. The annual rising of Sirius just before dawn, for example, coincided closely with the Nile’s flood, and the Egyptians used that connection to calibrate their calendar and agricultural cycle.

Some pyramid passages and temple axes are oriented so that specific stars or the Sun at solstices shine directly along them, like cosmic spotlights timed to the year. This wasn’t random; it reflects generations of careful watching and adjusting. They worked out a solar calendar of three hundred sixty‑five days, remarkably close to the true solar year, and kept track of decans – small star groups that rose at roughly ten‑day intervals – to tell time at night. Their fusion of architecture, religion, and astronomy turned stone into a permanent record of how the heavens moved above the desert.

3. The Maya: Calendar Builders of Mind‑Bending Precision

The Maya of Mesoamerica treated time almost like a sacred puzzle, and the sky was their key to solving it. Using naked‑eye observations from sites such as Uxmal and Chichén Itzá, they tracked the Sun, Moon, Venus, and other objects with uncanny care. Their famous Long Count calendar could name dates across thousands of years, while their shorter ritual and solar calendars interlocked in a complex cycle that governed ceremonies, politics, and everyday life.

What really shows how far ahead they were is their handling of planetary cycles. They charted Venus so precisely that their predicted appearances and disappearances of the planet line up closely with modern calculations, even after many years. Buildings like the Caracol observatory at Chichén Itzá have windows and alignments tuned to these Venus events and solar positions at solstices and equinoxes. Standing in front of those structures, it’s hard not to feel that the entire city was half a laboratory and half a living clock, all driven by the slow, patient motion of the sky.

4. The Ancient Greeks: From Myth to Mathematical Cosmos

The Greeks took a big leap: they tried to explain the sky not just as a place of gods but as a system that followed rules. Thinkers from different city‑states argued, calculated, and occasionally got things astonishingly right. Long before telescopes, they proposed that the Earth is spherical and even estimated its size with basic geometry and shadows. They also realized that the Moon shines by reflected sunlight and worked out methods to describe planetary motions with geometric models.

Even when they were wrong about the details, like imagining perfect circular orbits around Earth, they were pushing towards a universe that could be described with math instead of only myth. Star catalogs compiled in the Hellenistic period listed hundreds of stars with their positions and brightness levels, forming the backbone of navigation and later Islamic and European astronomy. Their willingness to turn observation into abstract reasoning helped shift humanity from simply watching the sky to trying to understand why it behaves the way it does, step by step.

5. Ancient Indian Civilizations: Cosmic Cycles and Advanced Calculations

In the Indian subcontinent, astronomy blended seamlessly with philosophy, ritual, and mathematics. Early texts and later astronomical treatises describe detailed planetary models, eclipse calculations, and the lengths of the solar year and lunar month with impressive accuracy. Scholars worked out methods for predicting eclipses and tracking the apparent motions of the Sun, Moon, and visible planets using numerical techniques that sometimes anticipate later trigonometric ideas.

What makes their approach feel especially advanced is the strong focus on cycles across enormous spans of time. They conceived of repeating ages and cosmic periods that stretched over vast durations, and then tied these grand ideas to practical tools like calendars and ritual timings. Table‑based calculations allowed them to find planetary positions for specific dates, which fed into astrology, religious ceremonies, and daily activities. Their work did not stay isolated; it interacted over centuries with Greek, Persian, and later Islamic astronomy, helping shape a shared global understanding of the sky long before modern science pulled it together.

Across these five civilizations, the stars were more than decoration; they were guides, warnings, clocks, and calculators. With simple tools and relentless observation, people who lived thousands of years ago built systems that could predict eclipses, align temples with solstices, and track planets with a finesse that still commands respect today.