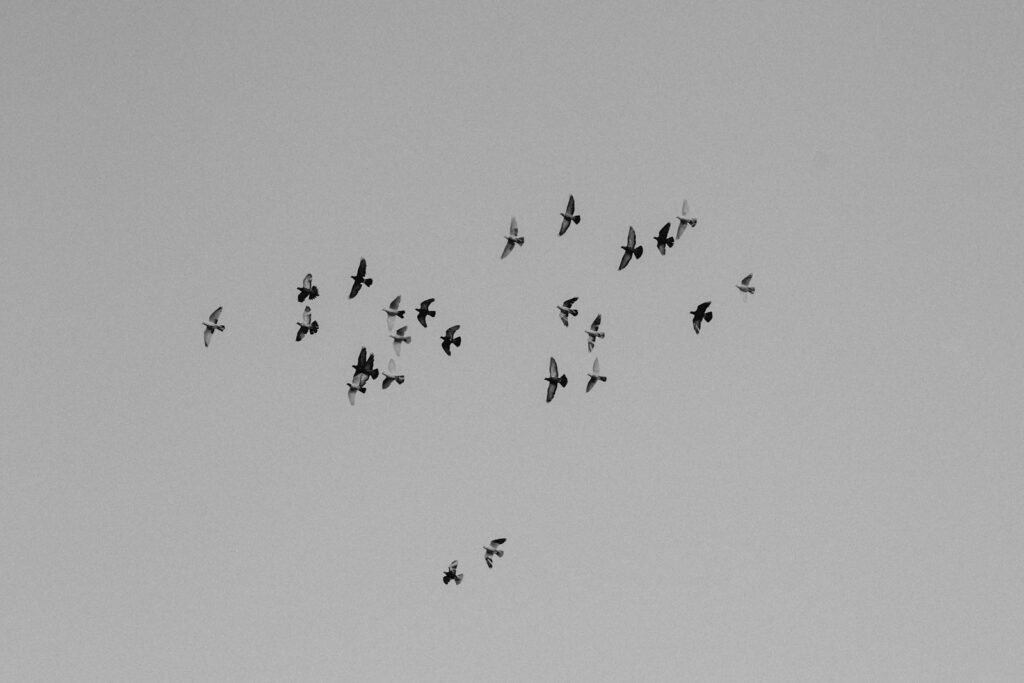

It happens in a blink: a whir of wings, a dark ribbon of life overhead, and then the sickening sight of bodies tumbling earthward. When videos surface – starlings in Europe, blackbirds in Mexico, songbirds over Midwestern streets – the mystery feels almost supernatural. Are these omens, accidents, or something we should have seen coming? Scientists say the answer is rarely a single cause and almost always a chain reaction, where weather, fear, light, and human choices collide. Understanding those links is how we transform shock into prevention, and a seemingly strange spectacle into a solvable problem.

The Hidden Clues

A sudden hush, a rush of air, and a flock begins to fold: the scene looks like chaos, but it’s full of signals if you know where to look. Field biologists start with evidence on the ground – bruising that hints at blunt-force impact, intact plumage that points away from predation, and the precise location of the fall. If carcasses cluster near a building or bridge, collisions rise on the list; if they’re scattered under open sky after a storm, weather forces come to the fore. The direction the flock was traveling, the time of night, even nearby streetlights can narrow the causes to a handful. It’s more detective story than disaster reel.

Patterns in the air matter too. Tight formations can behave like living fluid, where a single sharp turn ripples through hundreds of birds in milliseconds. In clear daylight, those cascades are graceful; in darkness or fog, they can end in concrete. I once watched a murmuration fold so close to a parking lot that people ducked instinctively, a reminder that spectacular coordination lives one misjudgment away from catastrophe.

When Weather Turns Violent

Storm outflows, called downbursts, can slam birds with a wall of sinking air strong enough to force them toward the ground. Hail can shred wings; sudden icing can load feathers with weight like wet coats. Even without drama, fast-moving cold fronts create wind shear that confuses flight control, especially for small migrants riding tailwinds at night. Birds that are hungry or exhausted from long flights have less margin for error and may fail to recover from a sudden gust. In extreme cases, thunderstorms create pressure and turbulence layers that behave like invisible stair steps – miss one, and you’re falling.

Then there’s the sky we can’t see. Geomagnetic disturbances can disrupt the subtle compass many migrants carry, nudging them off course or pushing them into poor weather at the wrong altitude. Smoke and dust decrease visibility and clog airways, turning a normal flight into an endurance test. When all these factors stack – turbulence, low oxygen, poor sightlines – groups can descend together, not because they choose to, but because the atmosphere gives them no good options.

Predators, Panics, and Physics

Flocks don’t just move; they think together, and panic spreads through them like a spark across dry grass. A single raptor diving at high speed can trigger a cascade of evasive maneuvers that forces hundreds of birds to compress, twist, and dive. In open country, that tactic works; over roads or rooftops, it can become a mass collision in seconds. At night, startle events – fireworks, sudden loud machinery, even a passing drone – can flush roosting birds into unfamiliar darkness where they misjudge distances. The result is a synchronized error, not a synchronized decision.

Physics sets hard limits. Birds share airspace at high density, and reaction times are fast but not infinite. If the lead edge of a flock dives, those behind must follow or crash into each other; if the flock meets ground sooner than expected, many hit almost together. In videos that look like a flock “dropping,” what you’re often seeing is a wave of avoidance that leaves no room to pull up. It’s heartbreaking, but it’s not mystery – it’s momentum, magnified.

Night Lights and the City Trap

Cities rewrite the night sky. Bright towers draw nocturnal migrants like lighthouses, pulling them lower and closer until glass, steel, and confusion do the rest. Reflections of trees in windows fool birds into diving toward phantom habitat; skyglow masks the stars that guide them, and low clouds can trap illuminated mist around skyscrapers like a glowing maze. During peak migration, the mix of fog and lights becomes especially dangerous because birds recalibrate using visual cues they can’t trust. Hundreds can collide in one night on a single complex, especially near water where routes converge.

But light is not the only urban trap. After-hours cleaning crews, flashing billboards, and nighttime sports events extend illumination well past sunset during critical weeks. Noise adds another layer: sirens and fireworks can flush roosts into lit corridors at bad angles, a recipe for group impact. The solution is straightforward but not trivial – reduce illumination when birds are moving, redesign glass, and favor downward-facing, warmer-toned lights that cut skyglow. Small changes across a skyline can translate into an entire flock making it through.

Toxins, Disease, and Human Footprints

Chemicals we spread in fields and cities can quietly set birds up to fail. Certain pesticides disrupt neuromuscular control, leaving individuals disoriented or weak mid-flight; seed treatments and rodenticides can create secondary poisoning that ripples through food webs. When a flock feeds together, multiple birds can suffer together, and a startled takeoff becomes a coordinated collapse. Disease compounds risk: outbreaks of avian influenza and botulism don’t usually cause mid-air drops en masse, but they weaken birds, making storms and night flights far more dangerous than they’d otherwise be. Stress from heat waves adds pressure, shrinking the energy margin needed to dodge obstacles.

Infrastructure plays a role, too. Powerlines, guy wires, and wind turbine arrays occupy corridors birds have used for millennia. Collisions with wires often happen in poor light or fog, and because birds travel in groups, a misjudgment by some can sweep others into the hazard. The fix is not abandonment but design – line markers that are visible to birds, turbine siting that avoids dense flyways, and seasonal curtailment during extreme migration pulses. When we map risk well, we can lower it for thousands of wings at once.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

People have watched flocks for as long as there have been campfires, but today’s toolset turns awe into analysis. Weather radar arrays, originally built for storms, now track migration at continental scales, showing nightly rivers of birds rising after dusk and ebbing toward dawn. Tiny GPS tags and light-level geolocators reveal when species climb, when they skim, and when they pause, turning mystery flights into annotated journeys. High-speed cameras and computer vision extract the geometry of murmurations and the chain reactions inside a panic dive, frame by frame. Bring these together, and a baffling video becomes a testable hypothesis.

Crowd-sourced observations have changed the pace of discovery. When people upload sightings and videos, researchers can triangulate events, match them to weather and light conditions, and understand which factors consistently show up together. It’s not just more data; it’s smarter context, the difference between a rumor and a pattern. And on nights when forecasts predict heavy migration, dashboards now warn cities in advance, helping officials dim lights and avoid repeat tragedies. The old intuition is still there, but the instruments finally keep up with the sky.

Why It Matters

Mass falls are not only disturbing; they’re signals that something in our shared environment has tipped out of balance. Many species already face headwinds from habitat loss and climate extremes, so sudden, preventable events can push local populations into long recoveries. Compared to the slow drip of daily mortality, group incidents draw public attention, and that visibility can catalyze change. Traditional approaches focused on single causes – blame the storm, blame the building – but the science shows layered risks demand layered solutions. When we act on that complexity, we protect more than a moment; we protect the system that makes migration possible.

This is also a story about how infrastructure learns. Just as road designs evolved to save drivers and pedestrians, skies over cities can be engineered for safer passage. Simple measures – targeted light reductions, bird-safe glass, wire markers – stack benefits quickly, especially during a few critical weeks each season. The cost is often small next to the payoff in saved wildlife and public goodwill. If we take the hint embedded in these falls, we turn a grim headline into a blueprint for better coexistence.

The Future Landscape

What comes next is a smarter sky. As forecasting for migration improves, cities can automate light reductions the way thermostats respond to weather, dimming only when dense waves of birds are overhead. Satellites and next-generation radars will refine altitude estimates, flagging times when strong winds or downbursts overlap with flight corridors so aviation and energy operators can adapt in real time. Expect building codes to evolve, with glass patterns and orientations chosen as deliberately as fire exits. The same machine learning that recognizes traffic jams on roads will start predicting them in airspace.

There are challenges we can’t ignore. Expanding satellite constellations and brighter LED installations threaten to increase skyglow if unmanaged, and climate volatility means harsher storms and heat stress will collide with migration more often. Balancing renewable energy expansion with safer turbine placement demands transparent data and regional planning. But the tools to navigate these trade-offs already exist, and the sooner we deploy them coherently, the fewer headlines will begin with a thud. The future is not bird-proof, but it can be bird-smart.

What You Can Do

Start with light. If you live or work in a building with nighttime lighting, turn it down during peak migration seasons in your region, and push for timers or motion sensors that keep illumination focused and brief. Treat big windows with patterns or decals that break up reflections birds mistake for sky; spacing matters, so aim for visible markers close enough that a small bird can’t slip through. Keep cats indoors during migration peaks, and skip lawn chemicals that add silent risks to already demanding journeys. When severe weather is forecast at night, expect birds to be stressed the next morning and drive carefully near bridges and waterfronts.

Report what you see. If you encounter a group fall, document conditions, note nearby hazards, and notify local wildlife authorities or a regional bird rescue – organized data beats viral shock every time. Support Lights Out initiatives, bird-safe building policies, and community science platforms that turn your sightings into protection. Encourage event planners to avoid fireworks near large roosts, especially in winter, when night flights are most disorienting. Small actions, multiplied across a city, can lift an entire flock. Will you look up tonight and help keep the sky open?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.