Some scientific questions feel big; others feel almost indecent to ask out loud. Why does consciousness exist at all – why is there a felt, inner movie rather than just blind electrical activity in a lump of tissue? For more than a century, neuroscience has mapped brain regions, charted neurons, and built ever-faster scanners, yet the raw fact of lived experience remains as slippery as smoke. Strangely, some of the most provocative clues are now coming not just from high-tech labs, but from ancient skulls, stone tools, and forgotten civilizations that lived and died without a word for “neuroscience.” To understand why anything in the universe is “like something” from the inside, scientists are starting to look backward as much as forward, hunting for the deep evolutionary and cultural roots of awareness. The result is a field that feels less like a tidy puzzle and more like a sprawling detective story that stretches from Paleolithic caves to quantum debates.

The hidden clues in a three-pound mystery

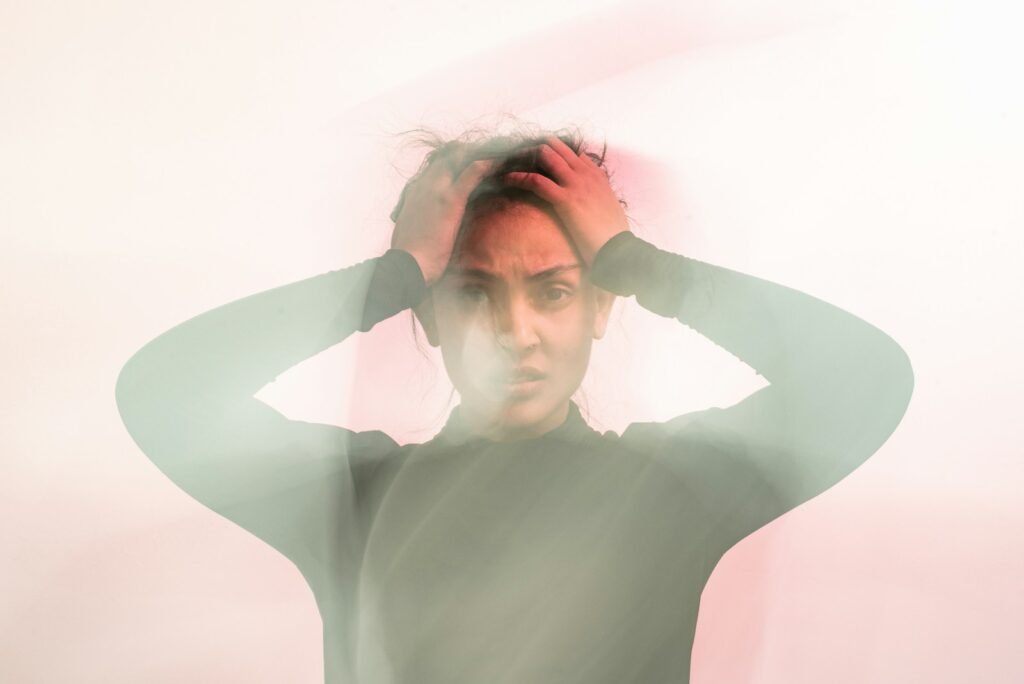

Imagine waking up one day with all your memories intact but no word, no concept, for “consciousness” itself – just raw experience, unlabelled. In a way, that is exactly how our species spent most of its history: conscious for hundreds of thousands of years, but only recently puzzled by what that really means. Neuroscientists today can track brain signals down to the millisecond and see which regions light up when you recognize a face, feel pain, or imagine the future. Yet the leap from firing neurons to the taste of chocolate or the sting of heartbreak remains unexplained, a gap philosophers call the “hard problem” of consciousness. It is like staring at the wiring diagram of an ancient machine and knowing perfectly how the cogs turn, but not why the machine occasionally dreams.

What is changing now is that researchers are treating that mystery less as an embarrassment and more as a legitimate object of study. Instead of asking only how brains process information, they are asking when in evolution subjective experience first appeared, how it varies across cultures, and what social conditions nurture or blunt it. That shift has opened the door to collaborations between archaeologists, anthropologists, cognitive scientists, and even historians of religion. They are not just cataloging artifacts and brain scans; they are trying to reconstruct what it felt like to be a person in a Neolithic village, a Bronze Age city, or a desert monastery. Curiously, the deeper they dig into the past, the stranger and more fluid consciousness itself begins to look.

From ancient tools to modern brain scans

At first glance, chipped stone tools and carved bones seem like the last place to look for answers about consciousness. But archaeologists point out that tools encode decisions, attention, and planning in the very way they are shaped and worn. The shift from simple sharp flakes to carefully crafted hand axes, and then to composite tools like spears and sickles, traces an increasing ability to imagine future scenarios, coordinate with others, and adjust behavior – all hallmarks of a richer internal life. When you hold a finely balanced obsidian blade, you are holding a fossilized trace of someone’s mental rehearsal of cutting, hunting, or carving long before it actually happened.

Modern neuroimaging adds another layer, showing that many of the brain regions involved in tool use overlap with those that light up during complex planning and self-reflection. Regions in the prefrontal cortex and parietal lobes, crucial for organizing sequences of action, also support our sense of narrative self: the feeling of being a single person stretched across time. As ancient societies developed more elaborate tools, writing systems, and trade networks, these networks in the brain were likely pushed into more sophisticated patterns of use. It is not that a stone axe “caused” consciousness, but that the demands of living in tool-saturated, socially dense worlds may have sculpted brains in ways that made self-awareness more elaborate, more story-like, and harder to ignore.

Hidden wonders of ancient minds

Cave paintings, ritual objects, and early mythic texts often get treated as art or religion, but they can also be read as field notes from the interior lives of ancient people. When Paleolithic artists painted animals with extra legs or blurred outlines, some cognitive scientists see not clumsiness but an attempt to capture motion and layered perception, something like an ancient animation frame. Later, intricate mandalas, labyrinths, and symbolic diagrams from different cultures may reflect deliberate experiments in focusing attention and altering ordinary experience. These are not just decorations; they are technologies for tuning consciousness, as intentional as any laboratory protocol today.

There is a growing argument that long before anyone wrote philosophical treatises, cultures explored consciousness through ritual, music, fasting, and psychedelics. Archaeological evidence of fermented beverages, psychoactive plants, and carved mushroom stones suggests that many societies took states of altered awareness seriously enough to encode them in their material culture. Rather than assuming these practices were mere superstition, some researchers now see them as early attempts to probe the edges of the self – crude but persistent experiments on the nature of mind. In that light, the question of why consciousness exists at all may have been hiding in plain sight in bonfire circles and temple rites, framed not as a puzzle about brains but as a lived, shared mystery.

The science of subjective experience

In the past few decades, consciousness has gone from philosophical side project to a serious neuroscientific target. Researchers design clever experiments where they can distinguish between brain activity that supports mere perception and activity linked with actual awareness. For instance, volunteers may be shown images so faint or brief that they sometimes see them and sometimes do not, even though the visual signal hitting the retina is identical. Comparing brain scans from the “seen” and “unseen” trials lets scientists isolate networks associated with the feeling of seeing. These studies suggest that consciousness arises when information is both widely broadcast across brain regions and tightly integrated into a unified pattern.

Several leading theories compete to explain how that pattern comes together. One framework emphasizes global broadcasting, proposing that when information wins a kind of neural competition, it becomes available to multiple systems at once, from language to decision-making. Another focuses on the degree to which different parts of the brain influence one another, arguing that experience corresponds to highly integrated yet differentiated states. A third provocative line of work suggests that brains build a simplified internal model of themselves and then mistakenly identify with that model as “I.” None of these theories has yet cracked the hard problem, but they at least give scientists levers to push, predictions to test, and a way to connect flickering neural activity with the ancient, stubborn fact of inner life.

Why it matters that the universe can feel itself

It is tempting to treat consciousness as a kind of philosophical luxury item, interesting but not especially urgent. In reality, it sits at the crossroads of some of the most consequential choices we face as a species. Medical decisions about people in comas or with severe brain injuries depend on whether we think there is still someone “home” inside a damaged brain. Legal and ethical debates about animals, from octopuses to great apes, hinge on whether their behavior reflects mere reflexes or some form of subjective experience. Even the growing conversation about artificial intelligence crashes headlong into questions about whether a machine could ever truly feel, or only simulate feeling with uncanny precision.

There is also a quieter, more personal stake. How we think about consciousness shapes how we see ourselves, each other, and our place in the universe. If experience is just an incidental by-product of computation, our lives can start to feel like elaborate illusions riding on mindless machinery. If, instead, consciousness reflects something rare and deeply structured – a fragile way the universe has of turning matter into meaning – then everyday feelings take on a kind of cosmic weight. In both cases, our intuitions about fairness, suffering, and value are riding on assumptions about what, and who, really feels. Getting clearer about why consciousness exists at all is not abstract; it is a way of getting clearer about what counts.

Global perspectives and the many stories of self

One of the most quietly revolutionary findings of recent decades is that consciousness does not show up in the same way across cultures. Anthropologists studying small-scale societies, urban megacities, and monastic communities describe strikingly different default senses of self. In some traditions, the individual is experienced less as a sealed-off interior and more as a node in a web of relationships, obligations, and spirits. In others, inner thoughts are not treated as especially private or uniquely important; what matters is how your actions mesh with the group. These differences do not imply different levels of consciousness, but they do suggest that how we learn to carve up the world – self versus other, inner versus outer – feeds back into how experience is structured.

Language appears to play a major role here. Research comparing people who speak languages with different ways of describing time, agency, or emotion finds subtle but real shifts in how they report their own awareness. Historical texts show that even within a single region, the way people talk about inner life can change dramatically over centuries, from describing being “visited” by thoughts to claiming ownership of internal mental states. This suggests that consciousness is not just a biological given but a moving target, shaped by stories, metaphors, and shared practices. The ancient puzzle of why consciousness exists at all may need to be reframed as many linked puzzles about why particular kinds of conscious selves crystallize in particular times and places.

Future landscapes: brain tech, synthetic minds, and new ethical fault lines

Looking ahead, the mystery of consciousness is colliding with rapidly advancing technology in ways that feel both thrilling and unnerving. Brain–computer interfaces are no longer science fiction; early versions already let people spell words or move robotic limbs using only their neural activity. As these systems become more sophisticated, they might offer unprecedented windows into patterns of awareness and perhaps even ways to nudge them. At the same time, increasingly complex AI systems are forcing scientists to clarify what would actually count as evidence of machine consciousness, beyond clever conversation and realistic images. The risk is not just over-assigning feelings to machines, but underestimating the moral weight of systems that really might begin to experience.

Several possible futures branch out from here. In one, advances in neuromodulation, psychedelics, and virtual reality make it routine to explore altered states safely and precisely, turning consciousness research into something like an applied engineering discipline. In another, social and regulatory backlash slows or blocks invasive brain tech, leaving some of the deepest questions unanswered for longer. Either way, it is hard to imagine that a world grappling with climate upheaval, mass migration, and widening inequalities will not also wrestle with who counts as a subject of experience in need of protection. The hidden wonder at the heart of all this is that for the first time in history, a conscious species is systematically trying to understand the conditions under which consciousness itself can arise, flourish, or be harmed.

How readers can lean into the mystery

For most of us, the frontier of consciousness research will not show up as a brain scan or a lab experiment, but as small shifts in how we pay attention to our own experience and that of others. One simple step is to treat your own awareness as data rather than as background noise: notice how your sense of self changes when you are stressed, immersed in a task, or quietly daydreaming. Paying closer attention to sleep, dreams, and the borderline states as you wake up or drift off can be surprisingly revealing, since they show consciousness dissolving and reassembling on a daily cycle. Reading across cultures – myths, memoirs, spiritual texts – can also expand your intuition about the sheer variety of ways humans have made sense of inner life, long before modern science arrived.

There are also more concrete ways to support the unfolding story. Publicly funded research in neuroscience, psychology, and anthropology remains crucial, especially studies that link lab work with real-world communities rather than just college volunteers and high-income countries. Ethical debates about AI, animal welfare, and end-of-life care all benefit when citizens demand nuanced, evidence-based conversations instead of slogans. Even small choices, like backing institutions that promote mental health care or pressing for humane treatment of nonhuman animals, rest on implicit stances about who and what can suffer. Ultimately, you do not need to solve the riddle of why consciousness exists at all to live as if it matters that it does – but noticing the riddle might change how you move through the world.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.