On a chilly dawn in Evergreen last month, a cow elk stepped out of the shadows and onto a cul-de-sac like she owned it. Sprinklers hissed, porch lights blinked on, and a calf tested the bounce of a backyard trampoline before melting back into the cottonwoods. Scenes like this are no longer rare cameos. They’re a pattern, the visible edge of a deeper migration shift that’s bringing elk closer to homes, parks, and schoolyards along Colorado’s Front Range and mountain towns. Scientists are tracking the change with new tools, and the story they’re uncovering is both practical and profound: the landscape is teaching elk new routes – and we’re part of the map.

The Hidden Clues

Look closely and the suburbs tell on themselves: clipped tulips, pressed-down fence rails, hoofprints stitched through pea gravel like punctuation marks. Doorbell cameras capture midnight parades, and neighbors swap trail-cam sightings like baseball cards. These little fragments add up to a big signal – elk are not just passing through, they’re learning the safe hours, the soft lawns, and the blind corners.

Biologists call it behavioral plasticity, the ability to change habits fast when the ground rules shift. Elk that once skirted neighborhoods now time their movements to the rhythm of rush hour and sprinklers. The herd’s elders pass on shortcuts and stopovers to calves, and within a few seasons, a workaround becomes a tradition.

From Ancient Trails to Modern Science

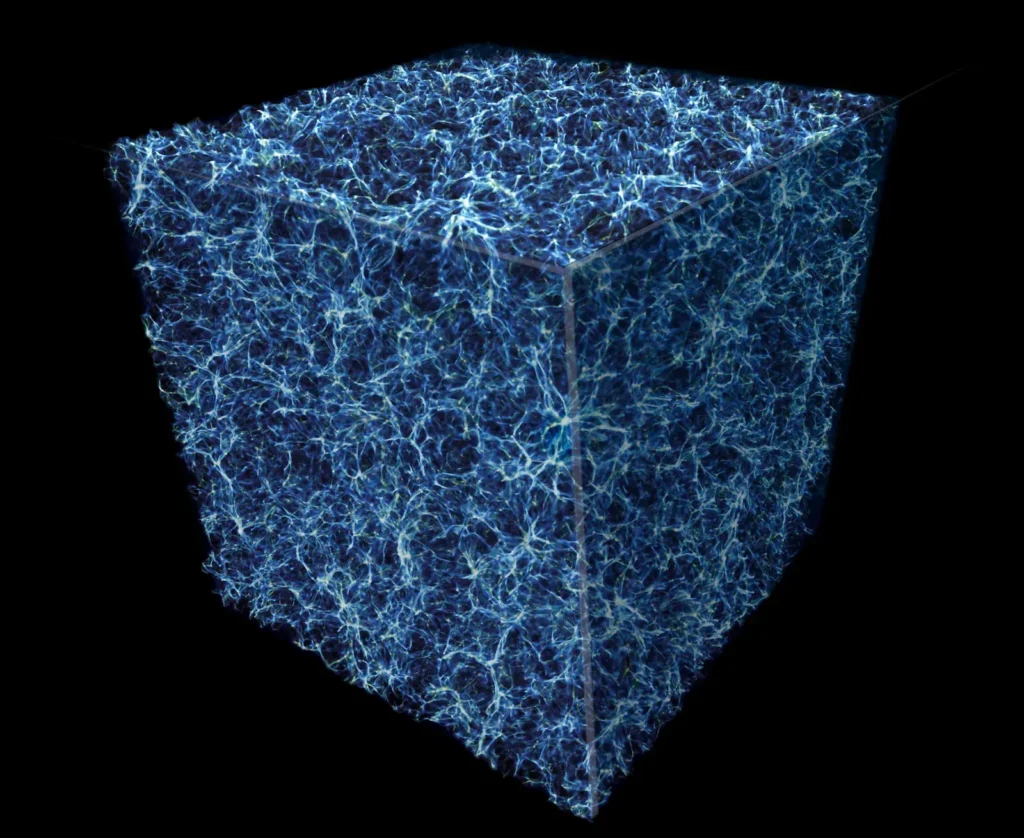

For generations, elk followed snowlines and green-up like clockwork, riding the spring “green wave” upslope and back down in fall. Today, those elegant routes are being remixed, and scientists are finally watching in high resolution. GPS collars plot thousands of points into living maps, revealing when elk slip under fences, pause at culverts, or funnel through a single backyard gate.

Those dots show something striking: some herds now treat neighborhoods like waystations, trading a quiet ridge for a lit street if it buys them time or calories. Researchers combine movement models with plant growth data to see where irrigated turf mimics mountain meadows, and where traffic or dogs push elk into nighttime travel. The result is a new atlas of migration, layered with our sidewalks and soccer fields.

The New Buffet: Lawns, Parks, and Golf Courses

Irrigation changes everything. When foothill grasses fade, sprinklers keep lawns and fairways green, serving protein at the very moment wild forage dips. Elk aren’t reading HOA bylaws; they’re reading calories. A watered green can outcompete a sunburned hillside, and a tree-lined park offers shade that a baked slope can’t.

There’s also predictability in neighborhoods – trash days, dog-walking waves, school bells. Elk learn the lull between dinner and dusk, then step out to graze with the confidence of regulars at a diner. It’s not a love affair with suburbia; it’s a pragmatic calculation that pays, especially in dry years.

Pressure and Peril: Hunting, Predators, and People

Hunting seasons create a moving shadow on the landscape, and some elk now treat towns as seasonal refuge. When pressure rises in surrounding forests, slipping toward porches can lower risk, at least temporarily. The math is messy: fewer arrows and rifles, but more cars, fences, and curious dogs.

Predators add another variable. As wolves were reintroduced to parts of western Colorado starting in late 2023, elk are reevaluating where they linger and when they move. Even without many wolves on the Front Range, the broader sense of risk can ripple through herds. Add daytime hikers, mountain bikers, and leaf blowers, and it’s no surprise elk pick the quietest window they can find.

Fire, Snow, and the Clock of Spring

Colorado’s seasons no longer behave like a metronome. Some winters end in a shrug and a dusting, while others dump late storms that seal off forage just as cows need it most. Spring green-up can sprint at low elevations, stall uphill, and leave a patchwork of mismatched meals across a mountainside.

Wildfire scars complicate the picture further. Fresh burns can explode with tender growth a year or two later, drawing elk like magnets, but closures and hazards can block access. In that scramble, neighborhoods with perennial water and predictable greenery act like emergency rest stops. It’s the same journey, rerouted by a calendar that keeps shuffling.

Why It Matters

Elk are charismatic, yes, but they’re also heavy, fast, and unpredictable when spooked. Collisions rise where migration lines cross arterials, and a startled cow defending a calf can pin a dog-walker against a fence. For homeowners, the costs show up as chewed shrubs and toppled garden fences; for elk, the bill comes due in injuries, stress, and reduced calf survival if mistakes stack up.

There’s a broader ecological ledger too. When herds linger in neighborhoods, they spend less time moving nutrients through wild valleys and meadows, and more time compacting lawns. Urban heat islands and artificial light at night can skew feeding and rest cycles. In that context, the return of elk becomes a test of whether wildlife and modern life can share space without eroding what makes both thrive.

- Vehicle-wildlife crashes cluster at known crossing hotspots and dusk hours.

- Artificial night light can shift feeding into narrower windows, raising stress.

- Irrigated patches keep plants green longer, altering traditional stopovers.

Global Perspectives

Colorado isn’t an outlier; it’s a chapter in a worldwide story of large animals adapting to human edges. Moose slip into Scandinavian towns to browse gardens, red deer thread through Scottish estates, and elk haunt the margins of Rocky Mountain gateway communities. The details change, but the pattern holds: animals map risk, reward, and routine with the precision of seasoned commuters.

Places that bend the curve do a few things well. They connect wild habitat across busy roads, steer foot traffic away from nursery areas in spring, and teach residents how to coexist without turning neighborhoods into feeding stations. Colorado has the talent and tools to do the same, and the suburbs are where that know-how will be tested most visibly.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

Old-school tracking – boot leather, scat, and snow prints – still matters, but it now pairs with models that forecast elk decisions hour by hour. Movement ecologists run step-selection analyses that weigh each turn on a path against roads, dogs, and forage. The point isn’t to micromanage elk; it’s to predict trouble and design ways around it.

Add high-resolution satellite data and you get real-time plant growth metrics layered over movement maps. Throw in doorbell-camera uploads and volunteer observations, and the data begin to breathe. What used to take years of inference can now be checked in weeks, and management can move from reacting to anticipating.

The Future Landscape

Expect more wildlife crossings where the data say they’ll save the most lives, and not just for highways – arterials and county roads matter too. Smart fencing that guides elk toward safe underpasses, plus seasonal trail reroutes during calving, can shrink the conflict footprint. Residents will see more targeted hazing, vegetation choices that are less palatable to elk, and trailhead signs that change with migration in near-real time.

On the research front, collars will get lighter, batteries will last longer, and models will flag new hotspots before the first hoofprint appears. Land-use plans can knit small open spaces into true corridors, while conservation easements hold the line where subdivision pressure is strongest. If we do this well, the suburbs become a permeable border instead of a wall – and the quiet magic of migration survives the century.

Living With Giants: A Call to Action

Everyone has a lever to pull. Homeowners can swap a few plants for species less tempting to elk, keep dogs leashed near greenbelts, and slow down at dusk along known crossing routes. Schools and parks can post seasonal advisories and steer activities away from calving spots for a few crucial weeks.

Local governments can invest in crossings where crash reports cluster, coordinate irrigation schedules to avoid drawing elk into traffic at peak hours, and protect small but strategic parcels that stitch together movement paths. As for the rest of us, we can give elk the space they need when they appear on our streets – and remember that a good view is also a responsibility. What small change will you make the next time a herd passes your block?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.