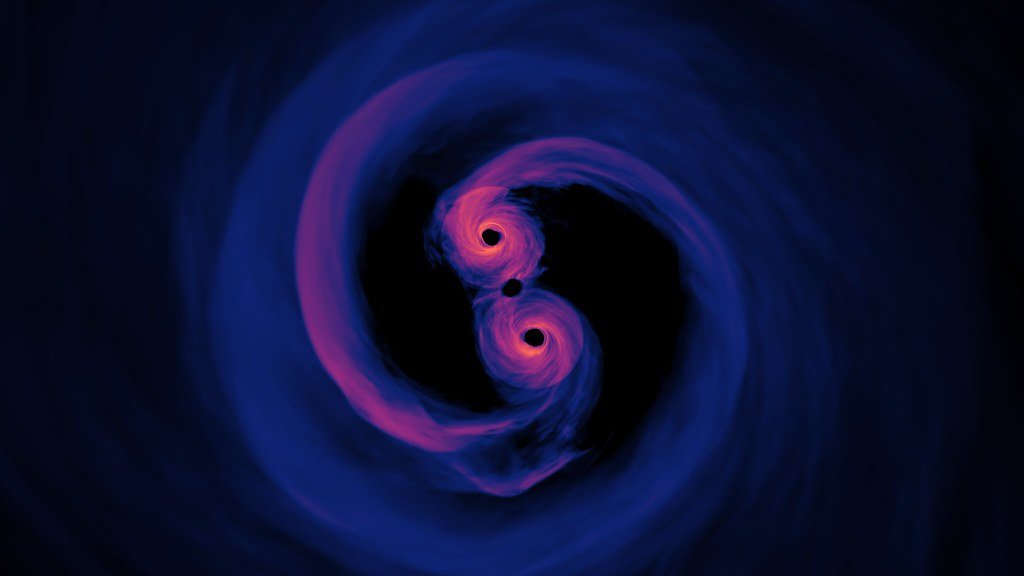

Detecting the Ripples of Repeated Mergers (Image Credits: Flickr)

Recent detections of gravitational waves from distant black hole collisions have provided astronomers with compelling clues about how these cosmic giants build themselves over time.

Detecting the Ripples of Repeated Mergers

Scientists announced the identification of two significant gravitational wave events, GW241011 and GW241110, captured in late 2024 by observatories including LIGO and Virgo. These signals marked the merger of black holes far beyond our galaxy, each event releasing ripples in spacetime that traveled billions of light-years to reach Earth. The analysis revealed unusual properties in the merging objects, suggesting they were not first-time colliders but products of prior unions. This discovery stood out because it aligned with predictions from models of dense stellar environments, where black holes frequently interact. Researchers noted that the effective spins and masses of the involved black holes deviated from typical isolated stellar collapse scenarios.

The events occurred just a month apart, allowing for comparative studies that strengthened the case for non-random origins. Data processing confirmed the signals’ authenticity, ruling out noise or artifacts. Such detections have become more routine since the first gravitational wave observation in 2015, yet these carried unique signatures pointing to evolutionary histories.

Understanding Hierarchical Black Hole Growth

Hierarchical mergers describe a process where black holes form not just from collapsing stars but through successive collisions in crowded regions like globular clusters. In these dense settings, a newly formed black hole can quickly pair with another, creating a larger remnant that later merges again. This chain reaction contrasts with the isolated field mergers expected in sparse galactic disks. Evidence for this mechanism had been theoretical until recent observations, including GW241011, provided direct support. The black holes involved often exhibit higher spins and intermediate masses, hallmarks of compounded growth.

Simulations of star clusters predict that such environments foster repeated interactions, with black holes sinking toward the center due to dynamical friction. Once there, gravitational slingshots and close encounters lead to binary formations. This model explains why some detected mergers involve objects too massive for single-star origins. The process also influences the overall population of black holes in the universe, potentially resolving gaps in mass distributions observed in earlier data.

Spotlight on GW241011: A Second-Generation Merger

Among the pair, GW241011 drew particular attention as the stronger candidate for hierarchical origins. At least one of its black holes appeared to stem from a previous merger, inferred from its spin magnitude and the binary’s orbital eccentricity. The primary black hole weighed around 40 solar masses, while the secondary tipped the scales at about 30, resulting in a combined remnant of roughly 65 solar masses. This configuration suggested formation in a globular cluster, where prior collisions could have produced the unusually aligned spins. Analysts used Bayesian inference to compare the event against population models, favoring hierarchical scenarios over first-generation ones.

GW241110 complemented this picture with similar but subtler indicators, including asymmetric mass ratios that hinted at cluster dynamics. Both events occurred at redshifts indicating distances of several hundred million light-years. The precision of the waveform modeling allowed scientists to test general relativity in strong-field regimes, finding no deviations. These findings built on prior detections like GW190521, which first hinted at intermediate-mass black holes.

Implications for Black Hole Evolution and Beyond

The confirmation of hierarchical mergers reshapes understandings of black hole demographics. It suggests that up to 10 percent of observed events may involve second- or higher-generation objects, concentrated in specific cosmic neighborhoods. This has ripple effects on models of galaxy formation, as growing black holes could influence star birth rates through feedback mechanisms. Future detectors like LISA will probe even more distant and frequent mergers, potentially mapping these hierarchies across cosmic time.

Additionally, these events bolster Einstein’s theory by matching predicted waveforms precisely. They also open doors to studying exotic environments, such as those around supermassive black holes. As data accumulates, astronomers anticipate a clearer picture of how black holes scale from stellar seeds to galactic anchors.

Key Takeaways

- GW241011 and GW241110 provide the strongest evidence yet for black holes formed via prior mergers in dense star clusters.

- These detections highlight spin and mass signatures that distinguish hierarchical growth from isolated collapses.

- They refine models of black hole populations and affirm general relativity in extreme conditions.

These gravitational wave insights reveal a universe where black holes evolve through relentless cosmic recycling, challenging static views of their origins. What aspects of black hole mergers intrigue you most? Share your thoughts in the comments.