Storm seasons don’t begin with the first snowflake; they begin with a whisper in the Pacific. After a year of neutral waters calming the tropical Pacific, indicators now point toward a weak, possibly brief La Niña emerging in late fall and early winter 2024–25. That shift matters because even a modest La Niña can tilt the odds for rain, snow, drought, and cold across the United States. Forecast centers currently place higher odds on La Niña by October–December, with the signal fading toward late winter and spring. In other words, the stage lights may brighten early, then dim – yet the opening act could still reshape the season ahead.

The Hidden Clues

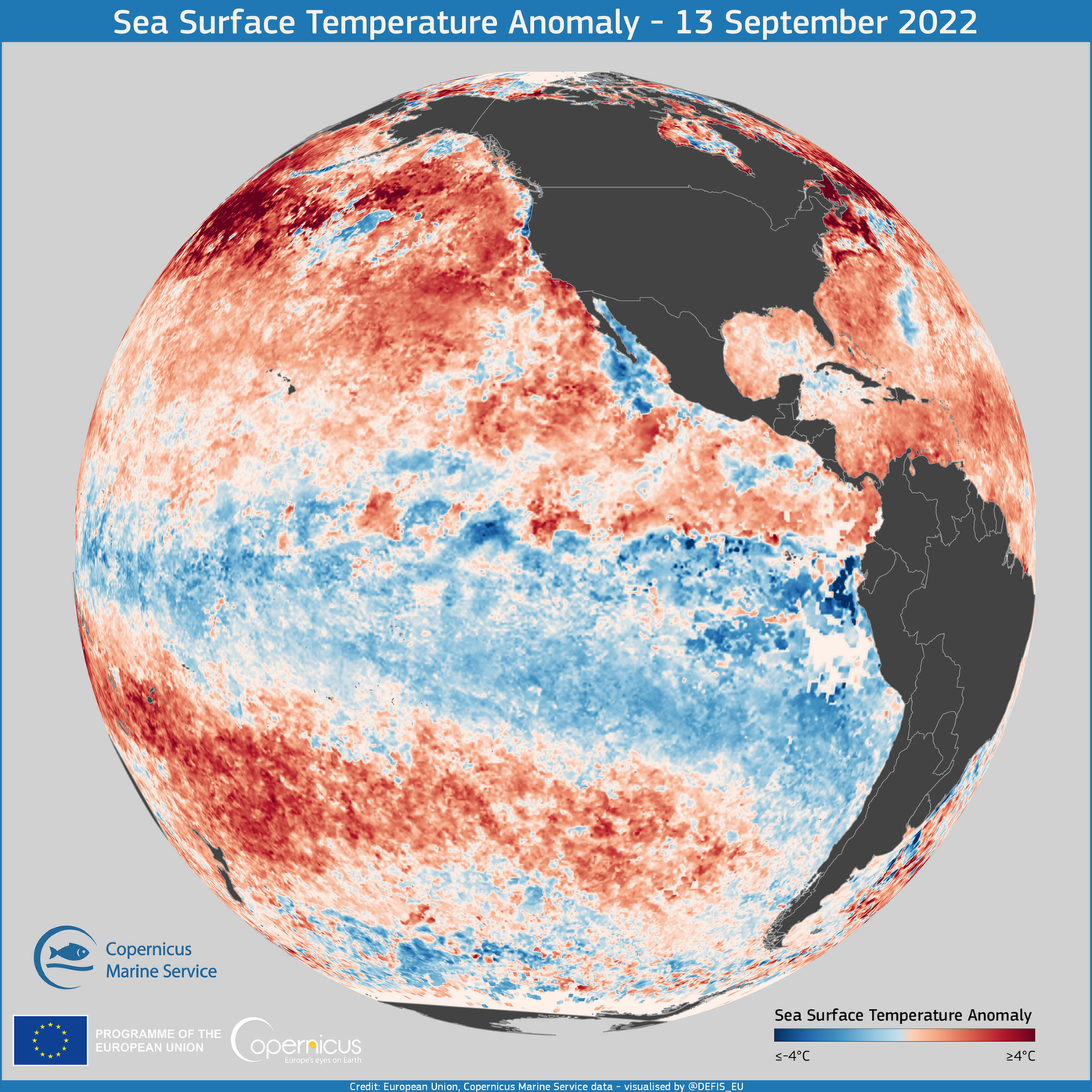

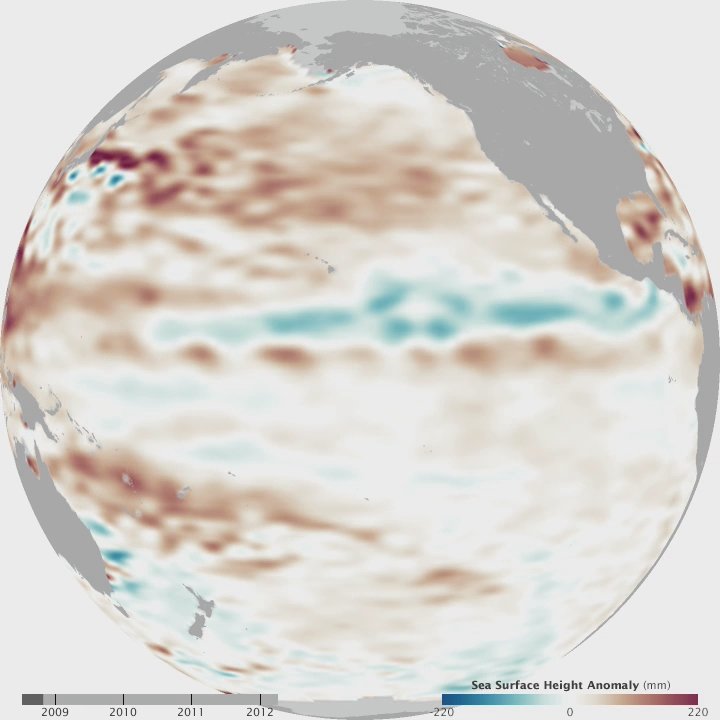

What if this winter’s plot twist is already being drafted by cool water thousands of miles from your front door? In recent months, cooler-than-average sea surface temperatures have nudged the central tropical Pacific toward the La Niña side of neutral. Trade winds have strengthened at times, helping upwell colder water and tilt the thermocline, the underwater boundary that separates warm and cool layers. These are classic breadcrumbs pointing to La Niña’s return, even if the signal is likely to be weak. Forecasters now favor La Niña thresholds during autumn into early winter, with the highest odds in the October–December window.

Confidence tapers into midwinter, as model guidance hints the pattern could relax back toward neutral by late winter. That nuance matters: the earlier the La Niña imprint, the more it can steer the first half of the season before local weather takes over.

Signals from the Pacific: What La Niña Actually Is

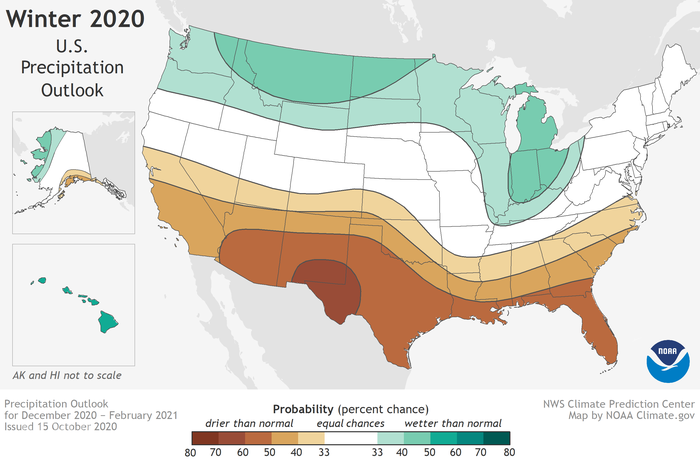

La Niña is the cool phase of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation, anchored in the Niño‑3.4 region along the equatorial Pacific. When those waters cool relative to average, the Walker circulation intensifies, shifting tropical thunderstorms westward and altering the high-altitude winds that guide storms across North America. Think of it like a river current tugging on the jet stream’s path. Over the United States, that typically favors a storm track bending into the Pacific Northwest and northern tier, while the southern tier sees fewer, weaker winter storms. The result is a familiar – but never guaranteed – pattern: wetter to the north, drier to the south.

These tendencies are best viewed as loaded dice, not a script. A weak La Niña means the dice are only slightly weighted, so local factors and day-to-day chaos can still roll surprises.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

Long before satellites, Pacific fishers read wind shifts and water temperatures the way you and I read headlines. Today, an armada of moored buoys, drifting floats, and satellites watches the equatorial Pacific for subtle changes in heat, currents, and wind. Those observations feed ensembles of global models – think dozens of “what if” runs – that map how the ocean‑atmosphere couple may evolve. Two major guideposts, the North American Multi‑Model Ensemble and international forecasts, currently tilt toward a weak La Niña in fall, with only modest staying power into deep winter. That split decision explains why outlooks lean one way while emphasizing uncertainty.

It’s a humbling reminder that the Pacific is the planet’s largest stage, and sometimes the scenery changes mid‑performance.

Regional Winners and Losers Across the US

If La Niña asserts itself early, the Pacific Northwest often sits in the wet seat, with more frequent storms and enhanced mountain snow. The northern Rockies and parts of the Upper Midwest can also see colder spells and bursts of snow as the jet stream dips south. By contrast, the southern tier – from Southern California across the Desert Southwest to the Gulf Coast and Southeast – tends to run drier and, at times, warmer. That raises flags for winter wildfire risk in the Southwest and water stress in parts of the South if autumn rains underperform. The Ohio Valley and Mid‑Atlantic land in the “messy middle,” where slight nudges in storm tracks can mean the difference between chilly rain and plowable snow.

Remember, weak La Niña winters can look patchy on a map: one county piles up snow while the next county wonders what all the fuss was about.

Storm Tracks, Snow Stories, and Flood Risks

La Niña winters often sharpen the Pacific jet into the Northwest, priming a parade of storms that can blossom into atmospheric rivers. That boosts odds for heavy rain at lower elevations and deep powder in the Cascades and northern Rockies, with occasional spillover into the northern Plains. Farther east, colder Canadian air can hook into clippers that dust the Upper Midwest and Great Lakes, sometimes triggering lake‑effect bursts after big Arctic shots. For the Northeast, weak La Niña is more of a coin flip: a couple well‑timed coastal storms can still deliver a blockbuster, but the baseline odds of frequent, widespread snow are lower than in strong El Niño years. Rapid thaws – especially after early‑season snows – can raise midwinter flood risk along some rivers if warm rain rides in on a southern detour.

Local ice storms remain the wild card along the southern edge of cold air, where shallow freezes meet Gulf moisture. Those hinge on timing more than any seasonal label.

Why It Matters

Seasonal outlooks aren’t trivia; they’re planning tools for water managers, grid operators, school districts, and growers. A weak, early‑peaking La Niña suggests front‑loaded storminess in the Northwest and a leaner storm diet for the southern tier, guiding reservoir rule curves and wildfire staffing. For agriculture, drier Southern winters can stress winter wheat in the southern Plains and temper recharge for soils ahead of spring planting across the Southeast. Energy planners watch for cold snaps across the northern states that can spike natural‑gas demand, even if the season’s average skews near normal. Public works crews in snow country track the likely cadence of plow operations and salt inventories to avoid midseason shortages.

Here are simple watch‑outs many communities use when a weak La Niña is in play: – Earlier storm frequency in the Pacific Northwest, favoring snowpack gains in the first half of winter. – Elevated odds of precipitation deficits across the southern tier, raising off‑season wildfire concerns. – Short, sharp cold spells in the northern tier that can still stress infrastructure despite a mild seasonal average.

The Future Landscape

Forecast centers will update probabilities monthly through autumn, and the early‑winter window is the critical pivot. If the tropical Pacific cools a touch more and trades hold firm, La Niña’s imprint likely sharpens from November into January; if not, the pattern may drift back toward neutral by late winter. Beyond ENSO, warm ocean patches in the North Pacific, pulses from the Madden‑Julian Oscillation, and Arctic variability can all bend the outcome. That’s why modern outlooks increasingly blend physics‑based models with machine‑learning tools that learn from past analogs and real‑time observations. The goal isn’t a perfect forecast – it’s a smarter risk envelope for the next four to twelve weeks.

Globally, a La Niña tilt can favor wetter conditions in parts of Indonesia and drier spells in segments of the southern tier of South America, with knock‑on effects for commodities and supply chains. Even a weak event can ripple through markets when it coincides with tight water or energy reserves.

Simple Ways to Engage

Start local: sign up for National Weather Service alerts, and check your regional Climate Prediction Center outlooks as they refresh each month. If you live in the Northwest or northern Rockies, prepare early for frequent storms – clear drains, service snow blowers, and review avalanche advisories if you recreate in the backcountry. In the South and Southwest, plan for stretches of dry weather by hardening landscaping against drought, inspecting defensible space, and conserving water during warm spells. Schools, small utilities, and neighborhood groups can run tabletop drills for cold snaps or winter floods, focusing on backup power, communications, and vulnerable neighbors. Farmers and ranchers can revisit winter forage plans and consult extension advisories that translate seasonal odds into field decisions.

Seasonal climate is a set of odds, not a promise. Treat it like a weather seatbelt: small effort now, big payoff if the road gets slick.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.