When you think of the deadliest disaster in human history, your mind might jump to wars, earthquakes, or volcanic eruptions. But nothing in recorded history has killed more people in such a short time than a microscopic enemy that swept across the globe in 1918. The Spanish flu pandemic didn’t just claim lives—it rewrote the rules of how societies function, how governments respond to crises, and how we understand the delicate balance between human civilization and invisible threats.

This wasn’t just another seasonal flu. Within 18 months, this viral assassin infected one-third of the world’s population and killed an estimated 50 to 100 million people. To put that in perspective, World War I, raging at the same time, killed about 17 million people over four years. Yet somehow, this pandemic has become a footnote in many history books, overshadowed by the war that dominated headlines. Today, as we navigate our own pandemic experiences, the lessons from 1918 feel more urgent and relevant than ever before.

The Mysterious Origins of a Global Killer

Despite its nickname, the “Spanish flu” didn’t actually originate in Spain. The pandemic likely began in military camps in Kansas or possibly in France, where American soldiers were stationed during World War I. Spain earned the unfortunate association simply because it was one of the few countries not censoring pandemic news due to wartime restrictions. Spanish newspapers freely reported on the devastating illness, making it seem as though Spain was uniquely affected. This early lesson in misinformation and media bias would prove remarkably relevant to how we handle pandemic communication today. The true origins of the 1918 virus remain debated, but scientists now know it was an H1N1 influenza strain that likely jumped from birds to humans, possibly through pigs as an intermediate host.

Why Young, Healthy Adults Became the Primary Victims

Most seasonal flu outbreaks follow a predictable pattern, primarily affecting the very young, elderly, and those with compromised immune systems. The 1918 pandemic flipped this script in a terrifying way. The virus specifically targeted healthy adults between ages 20 and 40, creating a devastating W-shaped mortality curve instead of the typical U-shape. Scientists believe this happened because the virus triggered a “cytokine storm”—an overactive immune response where the body’s defense system essentially attacks itself. The stronger your immune system, the more likely you were to die from your own body’s reaction to the virus. This phenomenon taught us that pandemic pathogens don’t always behave like their seasonal cousins, a lesson that proved crucial during COVID-19 when we saw unexpected complications in younger patients.

The Three Deadly Waves That Shaped History

The 1918 pandemic didn’t strike once and disappear—it came in three distinct waves, each with its own characteristics. The first wave in spring 1918 was relatively mild, almost like a typical seasonal flu that people initially dismissed. The second wave, beginning in August 1918, was the deadliest, killing millions within just a few months. A third wave struck in early 1919, less severe than the second but still claiming significant lives. This pattern taught epidemiologists that pandemics don’t follow simple timelines and that declaring victory too early can be fatal. The spacing between waves also revealed how virus mutations can change disease severity, knowledge that influenced modern pandemic preparedness strategies.

Cities That Acted Fast vs. Those That Didn’t

The tale of two American cities during 1918 became a legendary case study in pandemic response. Philadelphia held a massive Liberty Loan parade on September 28, 1918, despite knowing cases were rising. Three days later, hospitals were overwhelmed, and within six weeks, over 12,000 people had died. Meanwhile, St. Louis cancelled public gatherings, closed schools, and implemented social distancing measures at the first sign of trouble. Their death rate was roughly half that of Philadelphia. This stark comparison gave birth to the concept of “flattening the curve” and demonstrated that early, decisive action saves lives. The lesson resonated through every subsequent pandemic, including our recent experience with COVID-19, where similar patterns emerged between cities and countries with different response timelines.

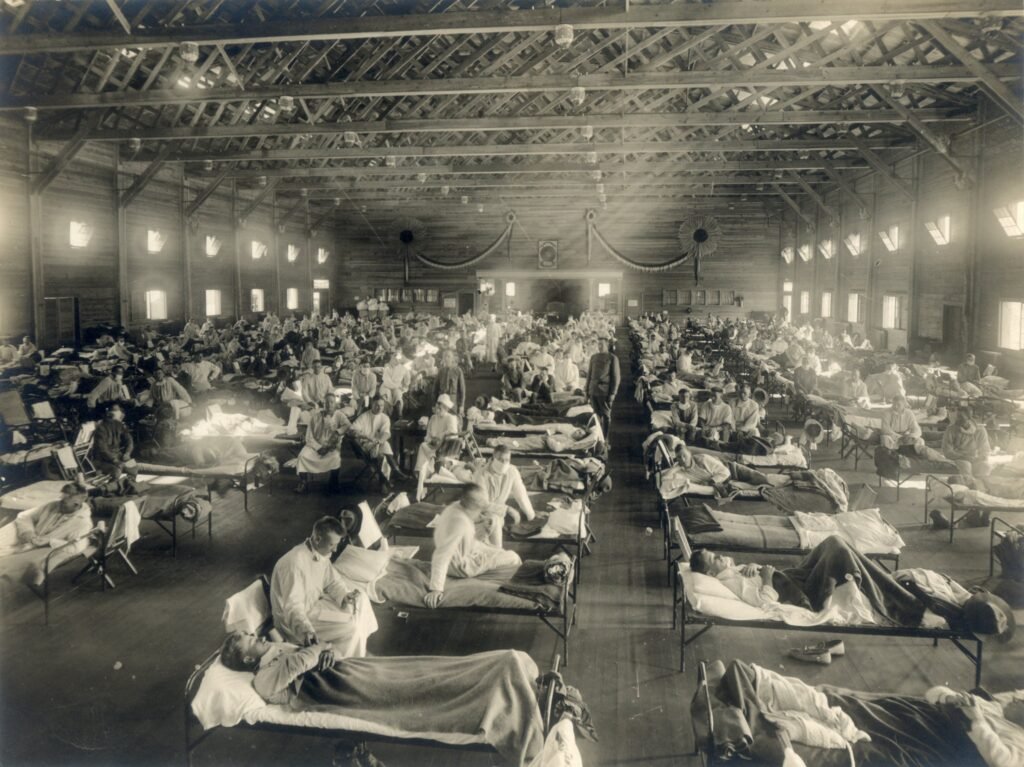

When Medical Systems Collapsed Under Pressure

Hospitals in 1918 weren’t prepared for the sudden influx of desperately ill patients. Medical facilities quickly ran out of beds, staff, and basic supplies like aspirin and coffins. Doctors and nurses fell ill at alarming rates, leaving skeleton crews to handle overwhelming caseloads. In some cities, medical students were pressed into service, and volunteers with no medical training tried to fill gaps. Bodies piled up in morgues and had to be stored in ice rinks and warehouses. This collapse taught health officials that surge capacity isn’t just about having enough beds—it’s about maintaining staffing, supply chains, and the entire healthcare ecosystem. Modern pandemic planning now includes detailed provisions for maintaining medical workforce health and alternative care sites.

The Economic Devastation Nobody Talks About

While the human toll of 1918 is staggering, the economic impact was equally transformative. Entire industries shut down as workers fell ill or stayed home in fear. Agricultural production plummeted just as the world needed food most desperately due to ongoing war. Small businesses collapsed, and unemployment soared in many regions. However, some industries—particularly those involved in healthcare, undertaking, and essential services—experienced unprecedented demand. The pandemic accelerated existing economic trends, much like COVID-19 would do a century later. This economic disruption taught economists that pandemics aren’t just health crises—they’re complete societal upheavals that require coordinated responses across all sectors of the economy.

How War Made Everything Infinitely Worse

The timing of the 1918 pandemic couldn’t have been worse, coinciding with the final stages of World War I. Military camps, with soldiers living in close quarters, became perfect breeding grounds for the virus. Troop movements spread the disease across continents faster than it might have traveled otherwise. Wartime censorship prevented accurate reporting of the pandemic’s severity, leaving populations unprepared. Resources that could have been used for pandemic response were tied up in the war effort. The dual crisis taught governments that national security isn’t just about military threats—biological threats can be equally devastating. This lesson influenced how modern militaries approach biosecurity and pandemic preparedness as matters of national defense.

The Science That Didn’t Exist Yet

In 1918, scientists didn’t even know that viruses existed. They could see bacteria under microscopes, leading many to initially blame the pandemic on bacterial infections. Without understanding the true cause, treatments were often useless or even harmful. High doses of aspirin, now suspected of worsening outcomes, were commonly prescribed. Antibiotics wouldn’t be discovered for another decade, leaving secondary bacterial infections largely untreatable. The lack of scientific tools meant that public health measures were based on observation and instinct rather than data. This scientific blind spot emphasized how crucial basic research is for pandemic preparedness, leading to massive investments in virology and epidemiology that continue today.

Social Distancing Before We Had a Name for It

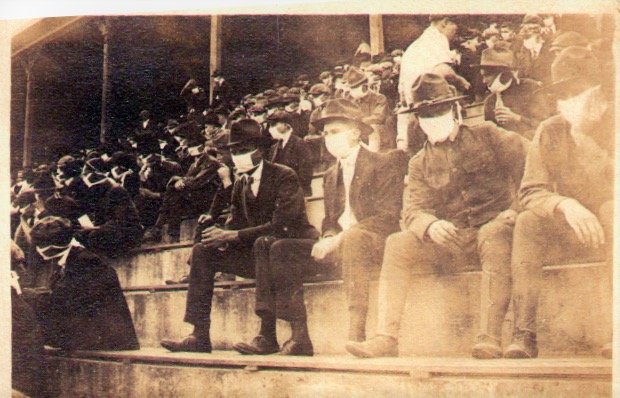

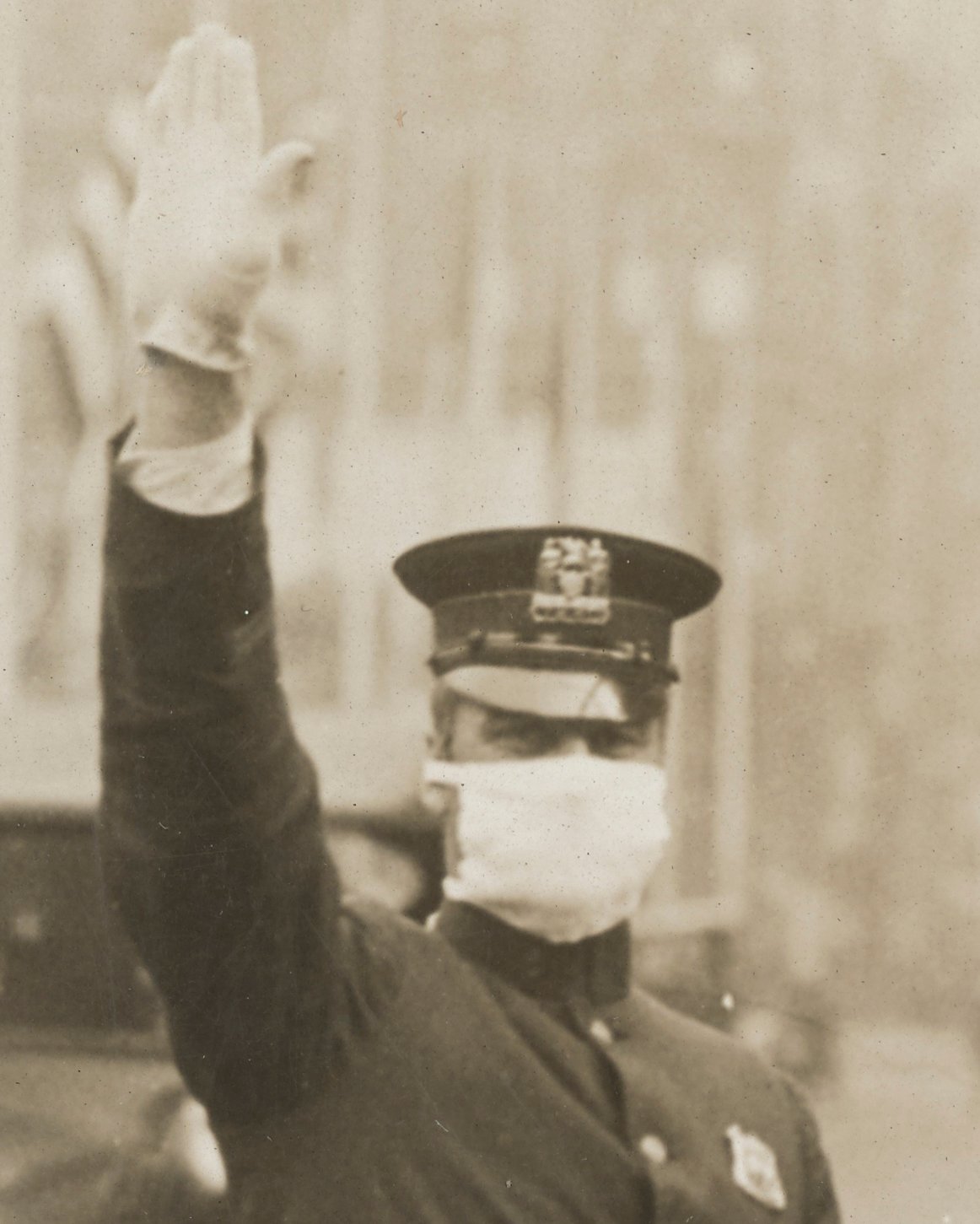

Long before “social distancing” became a household term, communities in 1918 were discovering its power through trial and error. Cities that closed schools, theaters, and churches saw lower death rates than those that kept them open. People intuitively began avoiding crowds and wearing masks, even without official guidance. Some communities organized outdoor schools and religious services to maintain social functions while reducing transmission risk. The concept of quarantine expanded from individual isolation to community-wide modifications of behavior. These grassroots discoveries laid the groundwork for modern non-pharmaceutical interventions, proving that human behavior modification can be as powerful as medicine in fighting pandemics.

The Mask Debates of 1918

Sound familiar? The 1918 pandemic featured heated debates about mask wearing that would seem remarkably contemporary. San Francisco made masks mandatory and even organized an “Anti-Mask League” formed in response. Some people embraced masks as civic duty, while others saw them as government overreach or questioned their effectiveness. Enforcement varied wildly—some cities fined people for not wearing masks, while others relied on social pressure. The debates revealed deep tensions between individual liberty and collective responsibility that persist in every health crisis. Despite the controversy, areas with higher mask compliance generally saw better outcomes, an early demonstration of how simple interventions can have profound impacts when adopted widely.

Communication Failures That Cost Lives

Government communication during the 1918 pandemic was often contradictory, delayed, or overly optimistic. Officials frequently downplayed the severity to avoid panic, but this led to complacency and poor decision-making by individuals and communities. Different agencies gave conflicting advice, and the lack of coordinated messaging created confusion. Some leaders tried to maintain morale by suggesting the pandemic was nearly over, even as cases surged. The communication failures taught public health experts that clear, consistent, honest messaging is crucial during health emergencies. Modern crisis communication strategies explicitly address the balance between preventing panic and ensuring people have accurate information to make good decisions.

How the Pandemic Changed Social Norms

The 1918 pandemic permanently altered how people interacted in daily life. Handshaking became less common, and many people developed lasting habits around hygiene and personal space. Public spitting, once common, became socially unacceptable in many places. The concept of staying home when sick, previously seen as a luxury only the wealthy could afford, began spreading across social classes. Traditional gathering patterns for everything from funerals to celebrations changed as people became more conscious of disease transmission. These social changes created a foundation for better public health practices that persisted long after the pandemic ended, demonstrating how crisis-driven behavioral changes can become permanently embedded in culture.

The Role of Class and Race in Pandemic Impact

The 1918 pandemic exposed and amplified existing social inequalities in ways that would become depressingly familiar. Poor communities, living in crowded conditions with limited access to healthcare, suffered disproportionately higher death rates. Factory workers couldn’t afford to stay home sick, while wealthier individuals could isolate in comfortable homes. Racial minorities faced additional barriers to medical care and were often blamed for spreading the disease. Indigenous communities were devastated, with some tribes losing significant portions of their population. These disparities taught public health officials that effective pandemic response must address underlying social inequalities, not just medical interventions. The lesson remains relevant as we continue to see how pandemics affect different communities unequally.

What Happened When the Pandemic Ended

Perhaps most striking about the 1918 pandemic is how quickly it disappeared from public memory. As the acute crisis passed, people wanted to forget the trauma and move on with their lives. This collective amnesia meant that few lessons were systematically captured or institutionalized. The pandemic’s end coincided with post-war celebrations, creating a complex emotional landscape where grief and relief mixed together. Many survivors suffered from what we might now recognize as post-traumatic stress, but mental health support didn’t exist. The rapid forgetting of 1918 taught historians and public health experts the importance of deliberately preserving pandemic lessons before collective memory fades.

Scientific Breakthroughs Born from Tragedy

The 1918 pandemic sparked scientific advances that continue to benefit humanity today. The crisis motivated major investments in public health infrastructure and disease surveillance. Researchers began developing better statistical methods for tracking disease spread and mortality. The pandemic highlighted the need for international cooperation in health matters, eventually contributing to the formation of global health organizations. Laboratory techniques for studying respiratory diseases advanced rapidly as scientists scrambled to understand the killer virus. Most importantly, the pandemic demonstrated the need for preparedness research during peaceful times, not just reactive research during crises. These scientific legacies created foundations for modern epidemiology and pandemic preparedness.

Early Warning Systems We Still Use Today

The 1918 experience taught communities the value of early detection and rapid response systems. Cities began developing better disease surveillance networks, even with the limited technology available. The concept of monitoring disease patterns to predict outbreaks emerged from this pandemic. Public health departments expanded their roles from treating individual patients to tracking population-level health trends. Communication networks between cities and states improved to share information about disease spread. These early warning systems evolved into the sophisticated global disease surveillance networks we rely on today, including everything from the CDC’s monitoring systems to international health alert networks.

Why Natural Immunity Wasn’t Enough

The 1918 pandemic definitively proved that relying on natural immunity to end a pandemic comes at an enormous human cost. Even after millions of deaths and infections, the virus continued to find new victims and evolve. Some communities that thought they had achieved immunity through infection were hit again by subsequent waves. The pandemic taught scientists that natural immunity alone is an unreliable and devastating strategy for pandemic control. This lesson became crucial for vaccine development strategies and helped establish the principle that prevention through vaccination or other measures is far preferable to treatment after infection. The concept of herd immunity through natural infection was revealed as both scientifically questionable and ethically problematic.

Global Cooperation vs. National Isolation

In 1918, international cooperation was limited by ongoing war and primitive communication systems. Countries largely faced the pandemic alone, with little sharing of information or resources. This isolation meant that lessons learned in one place weren’t quickly transmitted to others, leading to repeated mistakes. However, some international scientific cooperation did emerge, laying groundwork for future pandemic responses. The pandemic demonstrated both the need for global coordination and the challenges of achieving it during times of crisis. This experience influenced the development of international health organizations and treaties that recognize pandemics as global challenges requiring coordinated responses rather than purely national ones.

Technology Limitations That Seem Unimaginable Now

Fighting the 1918 pandemic with early 20th-century technology seems almost impossible from today’s perspective. There were no computers for tracking disease spread, no rapid communication systems for coordinating responses, and no sophisticated medical equipment for treating severely ill patients. Information traveled slowly, often by telegraph or mail, making real-time response impossible. Without reliable transportation, distributing medical supplies and personnel was extremely challenging. The technology limitations taught planners that pandemic preparedness must account for available tools and infrastructure, not ideal scenarios. Modern pandemic planning explicitly incorporates technology capabilities and includes backup systems for when primary technologies fail, lessons learned from 1918’s low-tech struggle.

The Mental Health Crisis Nobody Recognized

The psychological impact of the 1918 pandemic was enormous but largely unacknowledged at the time. Survivors dealt with trauma from losing family members, witnessing community devastation, and living through months of fear and uncertainty. Children who lost parents faced long-term consequences without adequate support systems. Healthcare workers suffered from what we might now call burnout and secondary trauma from treating overwhelming numbers of dying patients. The concept of mental health support during and after crises didn’t exist, leaving communities to heal emotional wounds without professional help. Recognition of these psychological impacts influenced modern pandemic planning to include mental health resources and support systems as essential components of crisis response.

The ghost of 1918 still walks among us, whispering warnings we’re only now learning to hear clearly. Every pandemic response plan, every early warning system, every debate about balancing individual freedom with collective safety traces its roots back to that devastating year. The people of 1918 paid an unimaginable price to teach us these lessons, sacrificing millions of lives to show us what works and what doesn’t when invisible enemies threaten our world. As we face future pandemics—and scientists assure us there will be more—we carry forward their hard-won wisdom, hoping we’re finally ready to listen. What would those 1918 survivors think of how we’ve applied their lessons today?