Imagine standing at the edge of a volcano crater where temperatures reach 800 degrees Fahrenheit, or stepping into an ice cave where sunlight has never touched the walls. Your first thought might be that nothing could possibly survive in such brutal conditions. Yet, deep within these seemingly lifeless environments, entire communities of organisms are not just surviving—they’re thriving in ways that would make even the toughest survivalist jealous.

The Masters of the Impossible

Life finds a way in places that seem designed to kill it. These organisms, called extremophiles, have evolved remarkable abilities that allow them to flourish where other life forms would perish instantly. They’ve been quietly rewriting the rules of biology for billions of years, showing us that life is far more resilient and creative than we ever imagined. Some can withstand radiation levels that would kill a human in minutes, while others feast on chemicals that would poison most living things. These biological marvels are scattered across Earth’s most inhospitable corners, turning barren wastelands into hidden metropolises of microscopic life.

Volcanic Powerhouses Living in Molten Hell

Deep within volcanic craters and hot springs, hyperthermophiles have made their homes in water that literally boils. These incredible organisms thrive at temperatures exceeding 250 degrees Fahrenheit, with some species actually requiring such extreme heat to survive. The Yellowstone hot springs harbor colorful mats of thermophilic bacteria that paint the landscape in brilliant oranges, yellows, and greens. One species, Pyrococcus furiosus, grows best at temperatures around 212 degrees Fahrenheit—the exact temperature that kills most other life forms. These volcanic residents have special proteins that remain stable under conditions that would instantly denature the proteins in your body.

The Antarctic Underground Empire

Beneath Antarctica’s frozen surface lies a hidden world of lakes and rivers that have been sealed away from sunlight for millions of years. Lake Vostok, buried under nearly 2.5 miles of ice, contains microorganisms that have evolved in complete isolation for eons. These psychrophiles, or cold-loving organisms, have antifreeze proteins in their cells that prevent ice crystals from forming and destroying their delicate structures. Scientists have discovered bacteria living in ice caves where temperatures drop to minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit. These frozen pioneers prove that even Earth’s most frigid environments can support complex ecosystems that operate on entirely different biological principles.

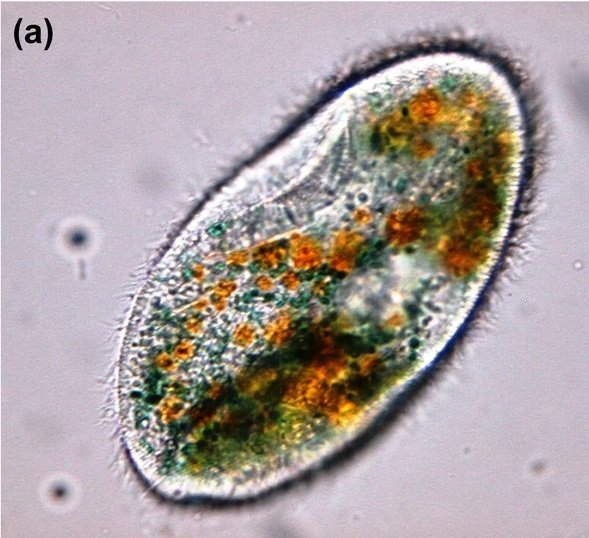

Acid Bath Survivors

In places where the pH levels would dissolve metal, acidophiles have carved out thriving communities. The Rio Tinto in Spain, with its blood-red waters and pH levels similar to stomach acid, hosts an ecosystem of acid-loving microorganisms. These remarkable survivors have evolved special mechanisms to pump excess hydrogen ions out of their cells while maintaining their internal pH at livable levels. Some species of Ferroplasma bacteria actually require sulfuric acid concentrations that would burn through human skin in seconds. Their cell walls are reinforced with unique compounds that resist the corrosive effects of their acidic homes.

Deep Earth’s Pressure Cookers

Miles beneath the ocean surface, where pressure reaches crushing levels equivalent to having a truck sitting on every square inch of your body, piezophiles have adapted to thrive. These deep-sea organisms possess modified proteins and cell membranes that actually require extreme pressure to function properly. The Mariana Trench, Earth’s deepest point, harbors unique species of amphipods and bacteria that would literally explode if brought to the surface too quickly. These pressure-loving creatures have evolved special enzymes that only work under the immense weight of miles of water above them. Their existence challenges our understanding of the physical limits of life itself.

Salt Crystal Cities

The Dead Sea and other hypersaline environments host halophiles—organisms that not only tolerate but require extreme salt concentrations to survive. These salt-loving microbes have turned the most mineral-rich waters on Earth into bustling biological communities. Halobacterium species contain special proteins that help them maintain water balance in environments where the salt concentration would instantly dehydrate most living things. Some halophilic archaea actually use salt crystals as tiny solar panels, harvesting light energy through unique purple proteins called bacteriorhodopsins. These organisms have transformed what appears to be a sterile, mineral-rich wasteland into a thriving ecosystem that glows with unusual colors.

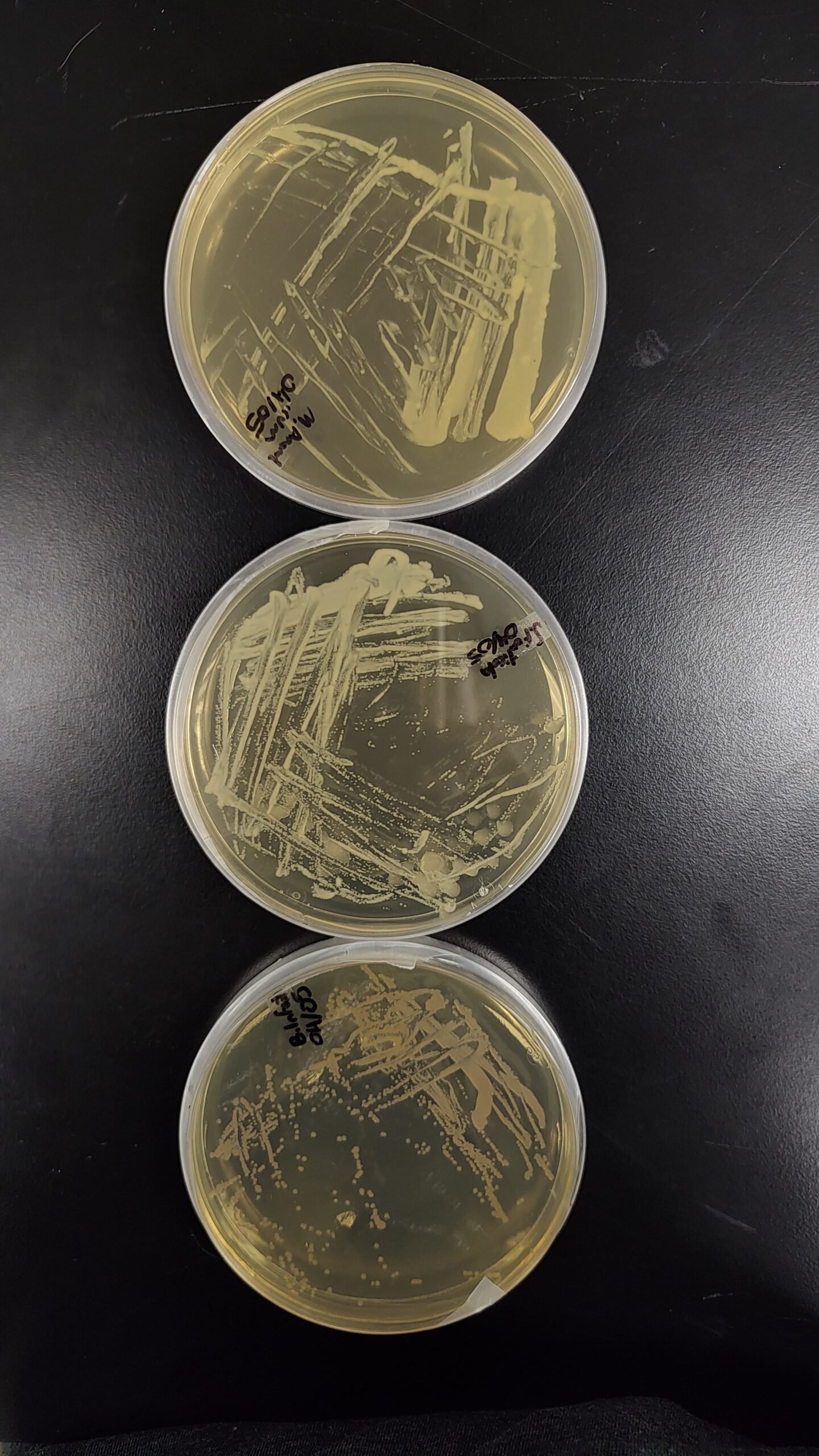

Radiation-Resistant Superorganisms

In the radioactive exclusion zones around nuclear disasters, radioresistant organisms continue to thrive where humans cannot safely venture. Deinococcus radiodurans, nicknamed “Conan the Bacterium,” can survive radiation doses 3,000 times stronger than what would kill a human being. These incredible survivors possess multiple copies of their DNA and lightning-fast repair mechanisms that can rebuild their genetic material even after it’s been shattered by radiation. Some fungi near the Chernobyl nuclear plant have actually evolved to use radiation as an energy source, much like plants use sunlight. These organisms represent evolution’s most extreme response to one of the most dangerous forces on Earth.

The Alkaline Miracle Workers

At the opposite extreme from acid-loving organisms, alkaliphiles flourish in environments with pH levels that would feel like swimming in bleach. Mono Lake in California, with its pH of nearly 10, supports vast populations of bacteria and algae that have adapted to these caustic conditions. These organisms have evolved specialized cell walls and transport systems that prevent the high pH from destroying their internal chemistry. Some alkaliphilic bacteria can actually break down cellulose and other tough organic materials more efficiently than their moderate-environment cousins. Their unique adaptations have made them valuable allies in industrial processes that require extreme pH conditions.

Desert’s Hidden Water Miners

In the world’s driest deserts, where rainfall might not occur for years at a time, xerophiles have mastered the art of extracting moisture from seemingly bone-dry air. These drought-resistant organisms can survive with water activities so low that they would mummify most other life forms. The Atacama Desert in Chile, often called the most Mars-like place on Earth, harbors microorganisms that can remain dormant for decades until the rare rainstorm awakens them. Some desert bacteria have evolved the ability to collect water directly from humidity in the air, using specialized proteins that act like molecular sponges. These water miners represent some of the most resource-efficient organisms on the planet.

Metal-Eating Miners

In old mines and metal-rich environments, metallotolerant organisms have learned to feast on heavy metals that would poison most life forms. These biological miners can concentrate metals like copper, zinc, and even gold within their cells without suffering toxic effects. Some bacteria can actually use metals as their primary energy source, essentially “breathing” iron or sulfur instead of oxygen. Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans can dissolve solid rock by producing acids strong enough to extract metals from ore deposits. These metal-munching microbes have revolutionized mining operations and offer potential solutions for cleaning up contaminated environments.

The Methane Specialists

In environments where methane gas seeps from the Earth, methanotrophic bacteria have evolved to use this potent greenhouse gas as their sole carbon and energy source. These organisms play a crucial role in controlling methane emissions from natural sources like wetlands, landfills, and gas seeps. Ocean floor communities around methane vents create complex ecosystems based entirely on these gas-eating bacteria. Some methanotrophs can consume methane so efficiently that they prevent significant amounts of this greenhouse gas from reaching the atmosphere. Their unique metabolism involves specialized enzymes that can break the strong chemical bonds in methane molecules that most organisms cannot touch.

High-Altitude Survivors

On mountain peaks where oxygen levels drop to barely breathable levels and UV radiation reaches dangerous intensities, alpine extremophiles have adapted to life in the thin air. These high-altitude specialists possess enhanced DNA repair systems to cope with increased cosmic radiation and specialized proteins that function efficiently in low-oxygen environments. Some bacteria found at elevations above 15,000 feet have developed unique pigments that act as natural sunscreen, protecting them from the intense UV radiation that would quickly kill lowland organisms. The discovery of life at such extreme altitudes has expanded our understanding of the upper limits of Earth’s biosphere and provided insights into potential life on high-altitude planets.

Cave Dwellers in Eternal Darkness

Deep within Earth’s cave systems, where sunlight has never penetrated, chemosynthetic organisms have built entire ecosystems without any connection to photosynthesis. These cave-dwelling communities derive their energy from chemical reactions involving sulfur, ammonia, or other minerals that seep through rock formations. Movile Cave in Romania, sealed from the outside world for 5.5 million years, contains 33 species found nowhere else on Earth. These cave specialists have evolved heightened senses and unique metabolic pathways that allow them to thrive in complete darkness. Some cave bacteria can even break down limestone and other rocks to extract nutrients, slowly reshaping their underground environments over geological time scales.

Boiling Water Beach Clubs

In geothermal hot springs scattered across the globe, thermophilic communities create living rainbows of heat-loving organisms. Grand Prismatic Spring in Yellowstone displays rings of different colored bacteria, each thriving at specific temperature ranges like biological thermometers. These thermal communities often form layered mats where different species occupy narrow temperature zones, creating complex ecosystems within just a few degrees of variation. Some thermophilic cyanobacteria can photosynthesize at temperatures that would instantly cook most plants, using specialized chlorophyll variants that remain stable under extreme heat. These boiling water gardens demonstrate how life can create beauty and complexity even in the most challenging thermal environments.

Drought Masters of the Extreme

In environments where water is so scarce that rocks themselves become desiccated, anhydrobiotic organisms have mastered the ultimate survival skill—coming back from the dead. These remarkable creatures can lose up to 99% of their water content and enter a state called cryptobiosis, essentially pausing all biological processes until water returns. Tardigrades, microscopic “water bears,” can survive complete dehydration for over a decade and revive within hours when rehydrated. Some desert plants and microorganisms produce special sugar compounds called trehalose that act like cellular glass, preserving their internal structures during extreme dehydration. These drought masters have solved one of biology’s greatest challenges—how to survive when the most essential ingredient for life completely disappears.

The Pressure-Resistant Deep Dwellers

In the deepest trenches of Earth’s oceans, where the pressure would instantly crush any surface-dwelling organism, barophilic communities have evolved to require these crushing depths to survive. These deep-sea specialists possess unique proteins that actually become more stable under extreme pressure, essentially using the weight of the ocean as a structural support system. The Challenger Deep, nearly seven miles below sea level, hosts organisms that have never experienced pressures lower than 1,000 times atmospheric pressure. Some deep-trench bacteria have gas-filled vesicles that act like biological submarines, allowing them to control their buoyancy in the crushing depths. These pressure-adapted organisms represent some of the most alien-like life forms on our own planet.

Cosmic Radiation Champions

In high-altitude environments and areas with elevated background radiation, organisms have developed extraordinary resistance to the type of cosmic radiation that damages DNA and cellular structures. Some bacteria can repair radiation damage to their genetic material faster than it occurs, essentially maintaining perfect DNA integrity even under constant bombardment. Certain fungi have evolved melanin-rich cell walls that act like biological lead shields, absorbing harmful radiation and converting it into usable energy. These radiation-resistant organisms have become crucial for understanding how life might survive in space or on planets with thin atmospheres that provide little protection from cosmic rays. Their remarkable repair mechanisms have inspired new approaches to treating radiation damage in humans and developing more effective cancer therapies.

Chemical Factory Survivors

In environments contaminated with industrial chemicals, heavy metals, and other toxic compounds, bioremediation specialists have evolved to not only tolerate but actually consume these dangerous substances. These pollution-eating organisms can break down complex chemical pollutants into harmless components, essentially turning contaminated sites into their own personal restaurants. Some bacteria can degrade petroleum hydrocarbons, while others specialize in neutralizing heavy metals or breaking down pesticides. Certain fungi can actually concentrate radioactive materials in their tissues, slowly cleaning contaminated soil over time. These environmental cleanup crews represent evolution’s response to human-made challenges, showing how life adapts to even the newest and most artificial extreme conditions.

Life’s ability to colonize Earth’s most hostile environments reveals a fundamental truth about our planet—there is virtually no place too extreme for some form of life to call home. These extremophiles have not only survived in conditions that would instantly kill most organisms, but they’ve thrived and created complex ecosystems that challenge every assumption we once held about the limits of life. From the scorching volcanic craters to the frozen depths of Antarctic ice caves, from acid pools that would dissolve metal to the crushing depths of ocean trenches, life has found ways to turn Earth’s harshest gardens into thriving communities. What other impossible places might be harboring life that we haven’t discovered yet?