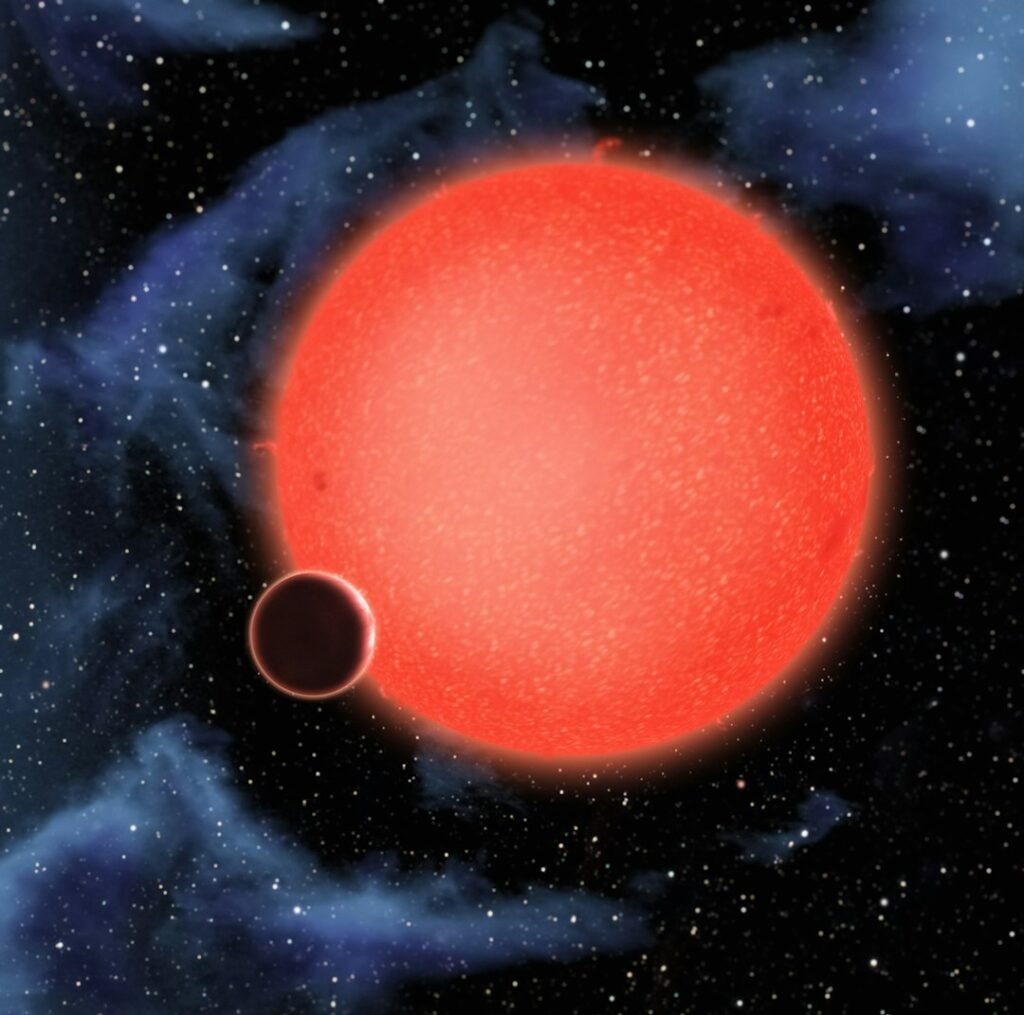

Picture this: you wake up tomorrow morning, but the golden sunrise you’re used to never comes. Instead, a dim reddish glow slowly creeps across the horizon, barely illuminating the world around you. This isn’t science fiction – it’s what our solar system would look like if our Sun were a red dwarf star.

Red dwarfs make up roughly three-quarters of all stars in our galaxy, making them the most common stellar neighbors. The nearest star to our Sun, Proxima Centauri, is actually a red dwarf. Yet despite their abundance, these cosmic lighthouses remain invisible to our naked eyes due to their incredibly dim nature. So let’s dive into this fascinating alternate reality where our solar system orbits one of these mysterious stellar giants.

The Dramatic Temperature Drop

If our Sun were suddenly replaced by a red dwarf, the first thing you’d notice is the bone-chilling cold. Red dwarfs have surface temperatures between 2,000-3,500 K and luminosities only 0.0001 to 0.1 times that of our Sun. This means Earth would receive dramatically less heat and light.

Since red dwarfs emit less energy, Earth would likely be too cold to sustain liquid water in its current orbit. To stay warm, our planet would have to be much closer to the star – perhaps even closer than Mercury is to the Sun now. Imagine Earth orbiting so close to its star that a year would last only a few weeks or even days!

Everything on the planet would appear dimmer and cast in red tones. Scientists think daytime on planets orbiting red dwarfs would never get any brighter than a sunset does on Earth. Your daily life would unfold under perpetual twilight conditions, fundamentally changing how plants photosynthesize and how ecosystems function.

The Inevitable Tidal Lock Phenomenon

If Earth were close enough to a red dwarf to sustain life, it could become tidally locked. This means one side would always face the star, creating extreme temperature differences between the permanent day and night sides. Half of our planet would experience scorching heat while the other half remained frozen in eternal darkness.

Planets in the habitable zone of a red dwarf would be so close to the parent star that they would likely be tidally locked. For a nearly circular orbit, this would mean that one side would be in perpetual daylight and the other in eternal night. This could create enormous temperature variations from one side of the planet to the other.

However, recent research offers some hope. Even a thin atmosphere can keep a planet spinning freely, giving it a day-and-night cycle like Earth’s. The result implies that many of the planets lying within the habitable zones of “dim suns” could have terrestrial-type climates. The key lies in atmospheric circulation patterns that could distribute heat more evenly across the planet’s surface.

A Revolutionary Change in Day and Night

Living on a tidally locked world would completely transform the concept of day and night as we know it. When a planet is tidally locked to its star, it creates what planetary scientists sometimes call a stellar eyeball region. The part of the planet directly facing the star is warmed, but beyond the terminator line, it’s not. This can create a planet with liquid water in the stellar eyeball but frozen water everywhere else.

For many years, it was believed that life on such planets would be limited to a ring-like region known as the terminator, where the star would always appear on or close to the horizon. It was also believed that efficient heat transfer between the sides of the planet necessitates atmospheric circulation of an atmosphere so thick as to disallow photosynthesis.

The terminator zone – that twilight band between the scorching day side and frozen night side – might become the most valuable real estate in this alternate solar system. Here, temperatures could remain moderate enough for liquid water and potentially life to exist.

Extreme Weather Patterns and Atmospheric Chaos

Due to differential heating, a tidally locked planet would experience fierce winds with permanent torrential rain at the point directly facing the local star, the sub-solar point. In the opinion of one author this makes complex life improbable. The weather would be unlike anything we experience on Earth.

Plant life would have to adapt to the constant gale, for example by anchoring securely into the soil and sprouting long flexible leaves that do not snap. Animals would rely on infrared vision, as signaling by calls or scents would be difficult over the din of the planet-wide gale. Evolution would take dramatically different paths under such extreme conditions.

Yet there’s a silver lining. Intense cloud formation on the star-facing side of a tidally locked planet can likely reduce overall thermal flux and equilibrium temperature differences between the two sides of the planet. Should a tidally locked planet possess a sufficient atmosphere, cloud coverage and albedo increase monotonically with stellar flux, increasing the resilience of the planet to variations in radiation.

The Threat of Stellar Flares and Radiation

Red dwarf stars aren’t exactly gentle cosmic neighbors. As more and more red dwarfs have been scrutinized for variability, more of them have been classified as flare stars to some degree or other. Such variation in brightness could be very damaging for life. These stellar tantrums can be absolutely devastating to nearby planets.

Red dwarfs are known to be extremely active magnetically and blast off huge flares that can torch any close-in planets. It takes roughly a billion years for them to settle down, and in that time the planet can suffer a runaway greenhouse effect it cannot recover from. During their youth, these stars are cosmic troublemakers.

Flares produce torrents of charged particles that could strip off sizable portions of the planet’s atmosphere. As a result, the atmosphere would undergo strong erosion, possibly leaving the planet uninhabitable. This creates a significant challenge for any potential life forms trying to establish themselves on red dwarf planets.

How Photosynthesis Would Transform

Photosynthesis on such a planet would be difficult, as much of the low luminosity falls under the lower energy infrared and red part of the electromagnetic spectrum, and would therefore require additional photons to achieve excitation potentials. Plants would need to fundamentally reimagine how they capture and use light energy.

Red dwarf stars emit most of their light in the red and infrared wavelengths. Thus, they would appear orange-red in the sky. This shift in the light spectrum would force plant life to evolve entirely different photosynthetic pathways, potentially using infrared radiation more efficiently than Earth’s plants use visible light.

Imagine forests of deep purple or black plants, optimized to absorb every available photon from their dim red star. The entire color palette of life would shift dramatically, creating alien-looking ecosystems that maximize energy capture from their feeble stellar companion.

Ocean Dynamics in a Red Dwarf World

Subsequent research has shown that seawater, too, could effectively circulate without freezing solid if the ocean basins were deep enough to allow free flow beneath the night side’s ice cap. Further, a 2010 study concluded that Earth-like water worlds tidally locked to their stars would still have temperatures above 240 K (−33 °C) on the night side.

Computer simulations of red dwarf exoplanets indicate that at least 90% of them are at least 10% water by volume, meaning they may have global oceans. These water worlds could develop unique circulation patterns, with warm equatorial currents flowing toward the frozen night side and cold deep currents returning to the day side.

The oceans might become the planet’s great equalizer, transporting heat from the blazing day side to the frozen night side. Deep ocean trenches could serve as thermal highways, maintaining liquid water beneath polar ice caps and creating a more hospitable environment than surface conditions might suggest.

The Dramatic Extension of Planetary Lifespan

Here’s where red dwarf systems truly shine: longevity. It is believed that the lifespans of these stars exceed the expected 10-billion-year lifespan of the Sun by the third or fourth power of the ratio of the solar mass to their masses; thus, a 0.1 solar mass red dwarf may continue burning for 10 trillion years. Because of the slow-motion fusion processes at the core of a red dwarf, this stage won’t arrive until the star is trillions of years old!

They will be the last stars to ever shine in the whole universe. Fun fact is that none of the red dwarfs in the universe has reached the late stages of their stellar life yet. They are still babies in their overall life cycle! This incredible longevity offers extraordinary opportunities for life to evolve and develop complexity.

It took 4.5 billion years for intelligent life to evolve on Earth, and life as we know it will see suitable conditions for 1 to 2.3 billion years more. Red dwarfs, by contrast, could live for trillions of years, as their nuclear reactions are far slower than those of larger stars, meaning that life would have longer to evolve and survive. The time scales for biological evolution become almost incomprehensibly vast.

The Fate of Outer Planets

In our red dwarf scenario, the outer planets would face a completely different destiny. Scientists estimate that gas giant planets, like Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune, make up just one in 40 planets orbiting red dwarfs. Our familiar gas giants might not even exist in a red dwarf system.

Without Jupiter’s gravitational influence, Jupiter is often described as the “big brother” planet of our solar system that made the formation and evolution of Earth possible. So if habitable planets are at all present around red dwarf stars, they would have been formed in ways very different from what happened on Earth. The entire architecture of planetary formation would be fundamentally altered.

The outer regions of our red dwarf solar system would remain frozen wastelands, but they might harbor subsurface oceans heated by tidal forces or radioactive decay. These hidden ocean worlds could become refuges for life, protected from the stellar violence occurring closer to the star.

A New Definition of the Habitable Zone

Any planet orbiting a red dwarf would need a low semi-major axis to maintain an Earth-like surface temperature, from 0.268 astronomical units (AU) for a relatively luminous red dwarf like Lacaille 8760 to 0.032 AU for a smaller star like Proxima Centauri. Such a world would have a year lasting just 3 to 150 Earth days.

While the likelihood of finding a planet in the habitable zone around any specific red dwarf is slight, the total amount of habitable zone around all red dwarfs combined is equal to the total amount around Sun-like stars, given their ubiquity. The cosmic real estate for potential life might be more abundant than we initially thought.

In the Milky Way, an estimated tens of billions of super-Earth planets occur in the habitable zones of red dwarf stars. This staggering number suggests that despite the challenges, red dwarf systems might host the majority of habitable worlds in our galaxy.

If our Sun were a red dwarf, Earth would be an entirely different world – possibly tidally locked, bathed in perpetual red twilight, and subjected to extreme weather patterns. Yet this scenario also offers tantalizing possibilities: trillions of years for life to evolve, potentially vast ocean worlds, and a completely reimagined biosphere adapted to infrared light.

The transformation would challenge every assumption we have about habitability, forcing life to find creative solutions to survive in this alien environment. While it might sound inhospitable, recent research suggests these red dwarf worlds could harbor their own unique forms of life, thriving in conditions we can barely imagine.

What fascinates you more about this alternate reality – the extreme challenges life would face or the incredible time spans available for evolution to work its magic? The universe might be filled with such worlds, each one a testament to life’s remarkable adaptability.