On Earth, when two pieces of metal touch, almost nothing happens that you can see. In space, the same simple act can quietly weld satellites together, jam moving parts, and even threaten billion‑dollar missions. This hidden phenomenon, called cold welding, reveals just how much our lives depend on something we rarely think about: Earth’s atmosphere. By stripping away air, dust, and water, the vacuum of space exposes the raw, atomic reality of metal itself. Understanding what happens when two metals touch out there is not just a curiosity – it is a window into the invisible protective shield that makes everyday engineering on Earth possible. And it is forcing scientists and engineers to rethink how we build the machines that will carry us deeper into the solar system.

The Hidden Clues: When Metals Forget Where One Ends and the Other Begins

Imagine pressing two clean blocks of aluminum together so perfectly that not a single speck of dust or molecule of air lies between them. To us, they still look like two separate objects – but to the atoms in those metals, the boundary disappears. In the vacuum of space, with no air, water vapor, or oxides getting in the way, metal surfaces can come into such intimate contact that their atoms mingle and bond as if they were a single piece. This is the essence of cold welding: no flame, no spark, just atoms quietly deciding that the “other” surface is actually part of themselves. It is as if two strangers met, forgot they had ever been separate, and instantly agreed they’d always been one.

On Earth, we almost never see this happen because thin films of oxygen, moisture, and microscopic dirt coat nearly every metal surface. Those layers act like social distance at the atomic scale, keeping surfaces from fusing. In orbit or on the Moon, however, constant exposure to vacuum and radiation scours and alters those layers, and repeated contact under pressure can strip them away. Once bare metal meets bare metal, the atoms are free to share electrons and lock together. To engineers, this is both a fascinating natural experiment and a quiet nightmare: a joint that forms when you do not want it, and often without warning.

From Ancient Tools to Rocket Science: The Long Road to Understanding Cold Welding

The basic idea behind cold welding is not new. Blacksmiths and metalworkers have long known that hammering and pressing very clean metal surfaces together can fuse them without fully melting the material. In traditional forge welding, intense heat and pressure help break up surface layers and push metal atoms close enough to bond. Space removes the need for the forge; the vacuum itself does the cleaning job, and mechanical contact supplies the pressure. What used to be a deliberate technique in a workshop becomes an uninvited guest on spacecraft.

In the mid‑twentieth century, as the space age dawned, engineers started to see strange sticking and seizing in vacuum tests and early satellites. Hinges that worked fine on Earth locked up in orbit. Connectors refused to separate. Experiments in ultra‑high vacuum chambers showed that metals such as aluminum, copper, and certain steels could bond firmly after being pressed together in the right conditions. As space missions grew more ambitious, cold welding shifted from a quirky lab result to a real engineering constraint. Designers now test materials and coatings in simulated space environments precisely to avoid repeating those early surprises.

How Metal Atoms Behave in the Vacuum of Space

At the atomic level, metals are like crowded neighborhoods of positively charged ions bathed in a shared sea of electrons. On Earth, the outermost layers are quickly capped with oxides – iron rusts, aluminum forms a tough oxide skin, and other metals build similar barriers. These thin skins are only a few atoms thick, but they dramatically change how surfaces behave. They block direct metal‑to‑metal contact, reduce adhesion, and help your car door open smoothly even after thousands of uses. In other words, corrosion is not just a nuisance; it is also a form of protection against unwanted welding.

In space, the situation flips. Hard vacuum encourages volatile substances to evaporate, and constant bombardment from solar radiation and micrometeoroids can crack, chip, or sputter away those protective layers. When two components slide, rotate, or press against each other, the mechanical motion can grind off the remaining oxide films locally. In that fresh, exposed patch, atoms from each side suddenly see no barrier. The metallic bonding that usually holds each object together now happily bridges the gap between them. This is why contact surfaces on spacecraft – such as latches, bearings, and electrical connectors – are designed with extraordinary care, using special coatings like gold, silver, or solid lubricants to keep raw metal atoms at arm’s length as much as possible.

Why This Matters: Earth’s Atmosphere as an Invisible Engineering Shield

The cold welding problem in space highlights something we take for granted every day: the air around us quietly protects our technology. On Earth, our atmosphere, with its oxygen and water vapor, creates those microscopic oxide layers and films that stop metal parts from fusing during routine contact. It means your zipper does not weld shut, your door hinges do not seize forever, and industrial machines can run for years with proper lubrication. Earth’s atmosphere is not just essential for breathing and climate – it is a stabilizing layer that lets mechanical systems operate without constantly fighting atomic-scale bonding.

Compared with traditional engineering on Earth, space hardware must be designed like it is going into a chemically stripped, hyper‑sensitive laboratory. Where a car manufacturer can rely on ambient air, cheap oils, and common steels, a spacecraft engineer has to assume worst‑case conditions: no air, extreme temperatures, and repeated cycles of contact in vacuum. Each hinge, latch, and docking mechanism is a potential cold welding site if not protected. This is why the study of tribology – the science of friction, wear, and lubrication – has become central to space mission design. In a way, cold welding is a reminder that the “normal” behavior of materials we rely on is actually a special case, made possible by Earth’s unique, life‑supporting atmosphere.

Unexpected Risks and Quiet Failures in Orbit

When cold welding strikes, it rarely announces itself with drama. Instead, it appears as a mechanism that suddenly resists motion, a connector that will not separate, or a satellite component that behaves just a little off. In extreme cases, a stuck valve or jammed hinge can cripple an entire mission. Space agencies have documented incidents in which components that worked perfectly during ground tests began to fail after prolonged exposure to vacuum, suggesting that changing surface layers were to blame. Engineers sometimes describe these as “silent welds,” because there is no spark, no heat, and no visible seam – just an invisible bond where there should have been separation.

The risk is especially high in places where metals repeatedly touch under pressure, such as telescope deployment mechanisms, solar array hinges, or docking systems. To reduce the danger, designers rely on several strategies:

- Using different metals in contact, since dissimilar metals are often less prone to fuse than identical ones.

- Adding coatings like gold, silver, or specialized dry lubricants that resist oxidation loss and reduce adhesion.

- Designing structures to minimize high-pressure sliding contacts and to distribute loads over larger areas.

Despite these precautions, long‑duration missions, like those in geostationary orbit or at distant planetary destinations, continue to test the limits of our understanding. Small changes in surface chemistry over years or decades can turn a low‑risk joint into a problem point.

Beyond Earth: What Cold Welding Teaches Us About Other Worlds

What happens when metals touch in space is not just an engineering headache; it is also a clue about how surfaces behave on airless worlds. On the Moon or asteroids, there is no thick atmosphere to cloak metals – or rocks – in oxygen and moisture. Lunar dust, for instance, is famously clingy and abrasive, and its sharp particles can scrape, polish, and gradually strip surfaces. Combine that with vacuum and extreme temperature swings, and you get an environment where cold welding and aggressive wear live side by side. Hardware on the Moon or Mars orbiters must endure a punishment Earth‑bound devices never see.

These insights are shaping how scientists think about building long‑term infrastructure beyond Earth. Lunar bases, asteroid mining equipment, and Mars orbiting stations will all need to cope with surfaces that behave far more “raw” than we are used to. That might mean more extensive use of ceramics, composites, and polymers in moving parts, or even designing systems that avoid metal‑to‑metal contact altogether where possible. The study of cold welding also feeds into basic planetary science, helping researchers understand how regolith grains stick, how rocks fracture, and how surfaces evolve under long‑term exposure to vacuum. In a way, every seized bolt or fused hinge in orbit is a small-scale experiment in how matter behaves without air.

The Future Landscape: Designing a Spacefaring World That Does Not Get Stuck

As we move toward a future of satellite swarms, commercial space stations, and crewed missions deeper into the solar system, the question of what happens when two metals touch in space becomes more urgent. More hardware in orbit means more potential contact points, more docking maneuvers, more robotic arms and moving joints. Engineers are exploring new coatings, such as advanced solid lubricants and nanostructured films, that can survive decades in vacuum without wearing away. Some are testing self‑healing materials that can re‑form protective layers after damage, mimicking the way skin repairs itself after a cut.

At the same time, digital design tools are helping teams simulate surface interactions down to the atomic level. This lets them predict where high‑risk contacts might occur and redesign components before they ever leave Earth. International standards bodies are also updating guidelines for space hardware, encouraging designs that reduce cold welding risks in critical components like docking ports and release mechanisms. The global push toward reusable rockets and spacecraft adds another layer of complexity: parts must not only work once, but survive repeated cycles of launch, space exposure, and reentry without seizing. Cold welding, once a niche curiosity, is now part of the mainstream conversation about how to build a spacefaring civilization that does not literally lock itself in place.

How You Can Engage: From Awareness to Supporting Better Space Engineering

It might seem like cold welding and vacuum friction are problems only for rocket scientists, but understanding them changes how we see our own planet. Knowing that Earth’s atmosphere quietly prevents metals from fusing in everyday life is a reminder of how finely tuned our home environment is. Simply learning about these hidden processes – and sharing them – is a way to deepen public appreciation for both planetary science and engineering. When people understand that even a door hinge behaves differently off‑world, space stops being an abstract void and becomes a real, demanding place.

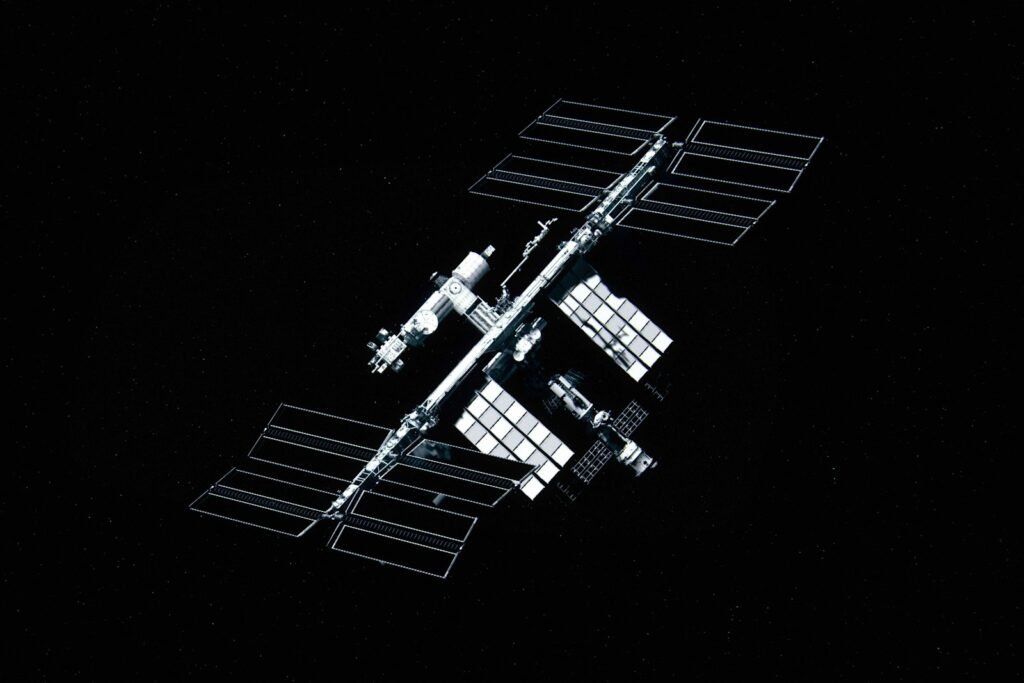

If you want to support progress in this field, you can follow and amplify the work of space agencies, universities, and labs that study materials in extreme environments. Many publish open results, animations, and mission reports that explain how they tackle issues like cold welding, tribology, and surface chemistry in orbit. Supporting science education, from local astronomy clubs to online lectures, helps build a generation of engineers and scientists who will design safer, more reliable space hardware. And the next time you hear about a satellite deployment or a docking maneuver at the International Space Station, you will know that behind the scenes, countless hours went into making sure two pieces of metal could touch in space – and then, crucially, let go.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.