Flamingos, in their bright pink feathers and upright posture, have been long symbols of grace and peace. But beneath their peaceful facade exists an unexpectedly fierce and clever strategy for feeding. New studies show that these birds are anything but passive filter feeders, they’re actually underwater predators, harnessing physics to generate teeny-tiny tornadoes that catch their prey. The discovery, spearheaded by biomechanics specialist Victor Ortega Jiménez, turns decades-old flamingo assumption on its head and may even spark new filtration solutions for getting rid of microplastics from water.

The Hidden Vortex: How Flamingos Turn Water Into a Trap

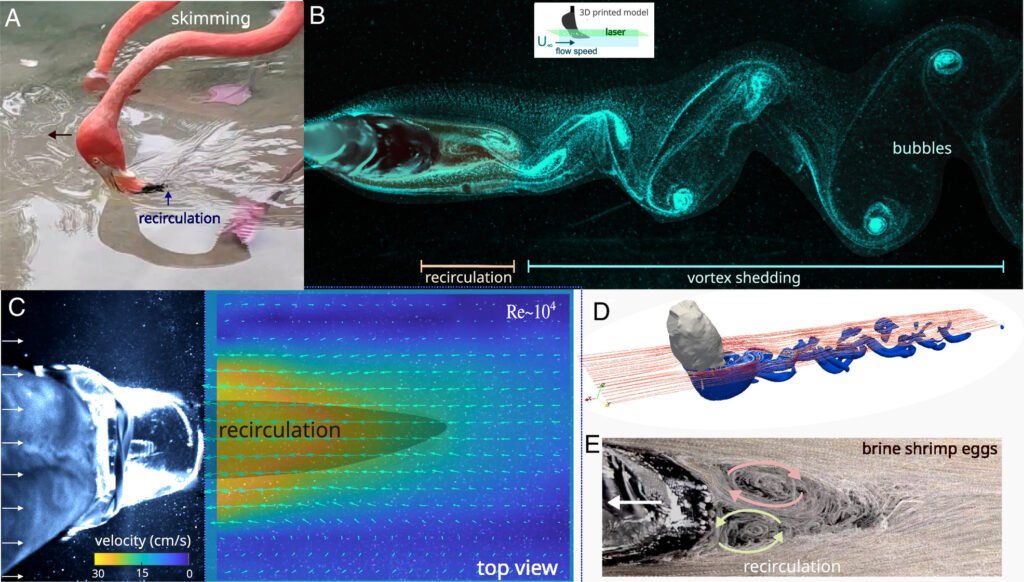

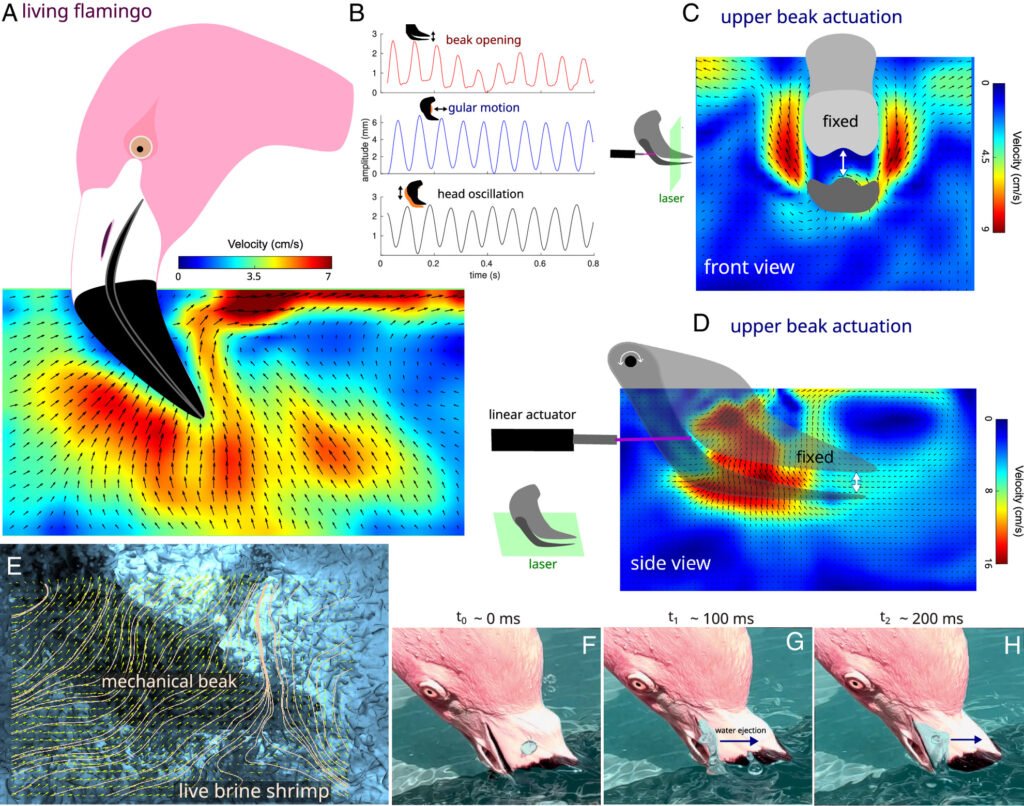

When flamingos dip their heads underwater, they aren’t just blindly sifting through mud. Instead, they generate powerful vortices swirling water currents that force prey like brine shrimp and tiny crustaceans into their beaks. Using high-speed cameras and 3D-printed models of flamingo heads and feet, researchers observed that the birds use rapid, piston-like head movements to create these whirlpools.

“Flamingos are predators,” explains Ortega Jiménez, an integrative biology professor at UC Berkeley. “They don’t just wait for food to drift by they actively corral it, like spiders weaving webs to catch insects.”

The Secret Weapon: Flamingo Feet as Sediment Stirrers

Before their heads even enter the water, flamingos use their webbed feet to kick up sediment. Unlike ducks or geese, flamingos have uniquely floppy feet that collapse when lifted, preventing suction in muddy waters. This allows them to “stomp dance” in place, churning up the lakebed and sending clouds of food particles swirling.

“Their feet act like underwater paddles,” says Ortega Jiménez. “Rigid webbing would just create turbulence, but their flexible feet generate directed currents that push prey toward their beaks.”

The Beak’s Clever Design: A Built-In Vortex Generator

A flamingo’s beak isn’t just to show its L-shape and flattened tip are precision-engineered for vortex creation. When submerged upside-down, the beak’s angle causes water to spiral around it, forming what fluid dynamicists call von Kármán vortices. These mini-tornados suck prey inward, where the flamingo’s “chattering” motion rapidly opening and closing its beak up to 12 times per second forces food into its mouth.

“It’s like a vacuum cleaner with a built-in stirring mechanism,” says Ortega Jiménez. “The faster they chatter, the more shrimp they catch.”

From Zoo Observations to Robotic Applications

The research started when Ortega Jiménez observed flamingos at Zoo Atlanta producing peculiar ripples while they were feeding. Curious, he collaborated with Georgia Tech engineers and the Nashville Zoo to record the birds in action. Employing lasers to measure water flow, they validated that flamingos produce vortices powerful enough to ensnare even speedy prey.

The findings aren’t just academic, they could lead to better filtration systems for removing microplastics from water or designing mud-walking robots inspired by flamingo feet.

Why This Changes How We See Flamingos

For years, scientists assumed flamingos were simple filter feeders, akin to baleen whales. But this research proves they’re dynamic hunters, manipulating their environment with sophisticated biomechanics.

“They’re not just standing there waiting for food,” says Ortega Jiménez. “They’re engineering their own feeding currents.”

The Next Frontier: Tongue Mechanics and Toxic Waters

Ortega Jiménez’s team is now investigating how flamingos use their piston-like tongues to suck in prey and how their beaks filter out toxic algae and salt. Given that flamingos thrive in some of Earth’s most caustic lakes, understanding their adaptations could have implications for water purification technology.

“Flamingos are master bioengineers,” he says. “Every part of their body is optimized for survival in extreme conditions.”

Conclusion: Nature’s Ingenious Predator

The next time you glimpse a flamingo wading immobile in shallow water, recall: under the surface, it’s conducting a high-speed, vortex-powered chase. Far from being sluggish grazers, flamingos are active predators, employing physics and accuracy of movement to harness water itself as a weapon. And we can never know? The same physical principles that enable flamingos to survive in poison lakes could one day enable us to detoxify our oceans.

Sources:

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.