Imagine standing on a grassy plain tens of thousands of years ago, listening to the voices of your ancestors echo across the landscape. What would you hear? Would it sound like song, like nonsense, or something oddly familiar? The idea that we, as modern humans, are connected to ancient people through the invisible thread of language is almost magical. Yet, when we try to peer back into the mists of prehistory, language slips through our fingers like smoke. The truth is, what we truly know about prehistoric human language is both fascinating and deeply mysterious—a puzzle with missing pieces, where each scientific discovery feels like unlocking a tiny new door into our shared human story.

The Elusive Nature of Prehistoric Language Evidence

When it comes to prehistoric language, the first hurdle is that language itself doesn’t fossilize. Unlike bones or stone tools, spoken words vanish into thin air the moment they’re uttered. We don’t have ancient recordings or scribbles from early humans that reveal how they spoke. Instead, researchers must become detectives, piecing together clues from anatomy, artifacts, and even DNA. Every theory is built on these tiny, fragile hints, making the study both exhilarating and exasperating. It’s a bit like trying to reconstruct a song from just the vibrations in the air after the music stops.

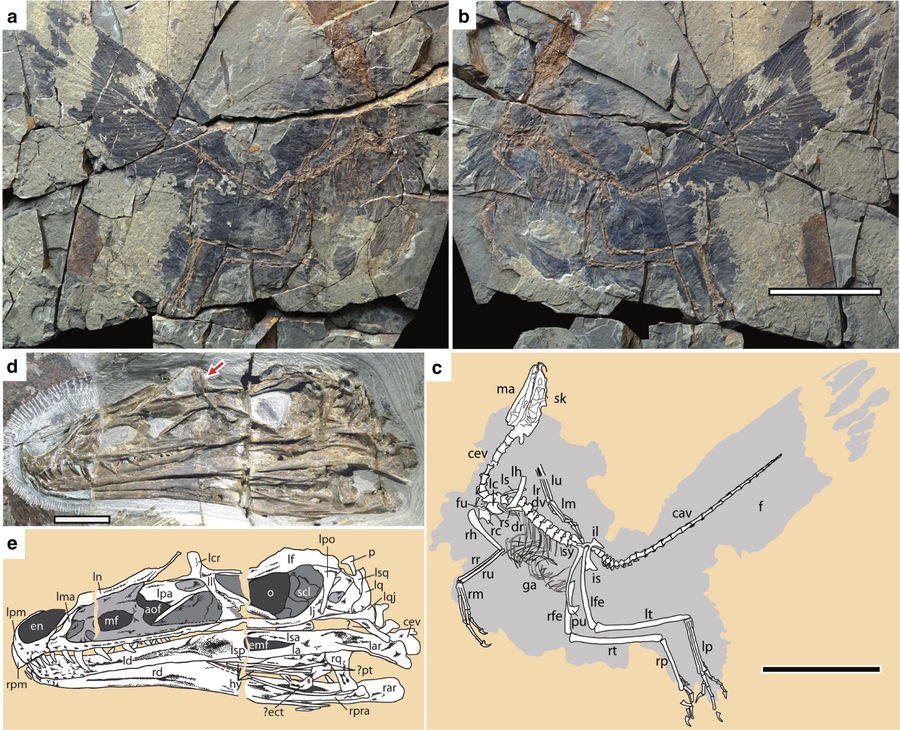

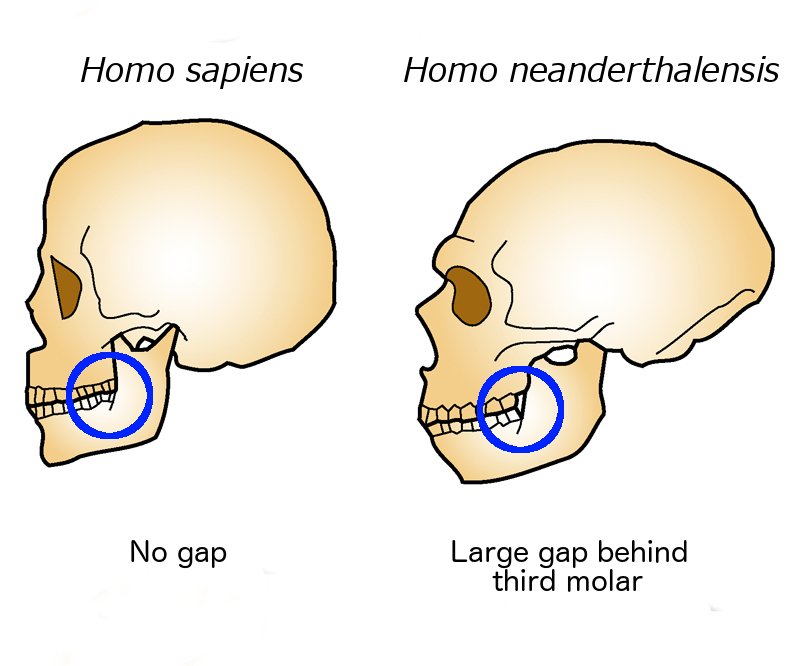

Fossil Clues: Hyoid Bones and Vocal Tracts

One of the most surprising pieces of evidence comes from a small, horseshoe-shaped bone in the throat called the hyoid. This bone anchors the muscles necessary for speech. Scientists have found Neanderthal hyoid bones that look almost identical to ours, suggesting these ancient cousins might have had the physical ability to speak much like we do. But having the right “hardware” doesn’t guarantee the software—language itself. Vocal tracts reconstructed from fossil skulls also hint at speech potential, but can’t reveal what was actually spoken.

Stone Tools and Symbolic Thinking

Language isn’t just about making sounds; it’s about sharing complex ideas. The leap from basic communication to true language may be linked to symbolic thinking—the ability to represent things that aren’t immediately present. Archaeologists have found intricate stone tools, cave paintings, and beads made by Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. These artifacts whisper of minds capable of symbolism, storytelling, and perhaps even gossip or poetry. The creativity etched in ancient stone may be as close as we’ll ever get to an echo of prehistoric words.

The Role of Genetics in Language Evolution

In the last two decades, scientists have turned to genetics for answers. One standout is the FOXP2 gene, sometimes called the “language gene.” Mutations in FOXP2 can cause severe speech and language disorders in modern humans. Astonishingly, both Neanderthals and Denisovans carried the same version of this gene as we do, suggesting a shared biological foundation for language. However, genes alone can’t tell us about vocabulary, grammar, or the stories our ancestors told.

Comparing Humans and Other Primates

What makes us different from chimpanzees and gorillas, our closest living relatives? Chimps can use basic sign language and understand symbols, but their “conversation” is limited and lacks grammar. This comparison helps highlight just how special human language is. While apes can learn hundreds of signs, humans can create endless new sentences with just a handful of words. This open-ended creativity likely emerged in prehistory, but exactly when and how remains tantalizingly unclear.

Did Neanderthals Have Language?

The question of Neanderthal speech is endlessly debated. Some researchers argue they must have had language, given their advanced tools and symbolic artifacts. Others point to differences in brain structure and social organization, suggesting their communication might have been less complex. The discovery of symbolic jewelry and burial practices among Neanderthals, however, keeps pushing the conversation forward—maybe these “cousins” weren’t so different from us after all.

The First Words: What Might They Have Sounded Like?

Imagine the very first human words—what could they have been? Some linguists theorize that the earliest words were probably names for family members, food, or dangers. Simple, urgent, and essential. There’s even a theory called “bow-wow theory,” which suggests that words began as imitations of natural sounds—birds, animals, the wind. Others think gestures and body language came first, with speech evolving much later as a more efficient way to communicate.

Theories on the Birth of Syntax

One of the wonders of human language is syntax—the rules for combining words into sentences. Syntax lets us say things like “The red bird sings at dawn,” not just “bird red sing.” When did this leap happen? Some argue it was gradual, with early humans stringing words together in loose, flexible ways. Others believe there was a rapid “big bang” of linguistic innovation, maybe sparked by a genetic mutation or a sudden burst of social complexity.

Gestures: The Silent Ancestors of Language

Before spoken words, many scientists believe our ancestors relied heavily on gestures. Even today, babies gesture before they speak, and people instinctively use their hands when talking. Some researchers propose that language began as a kind of “mime,” with gestures gradually replaced by sounds as vocal control improved. Watching chimpanzees or bonobos “talk” with their hands can feel like peering into our own distant past.

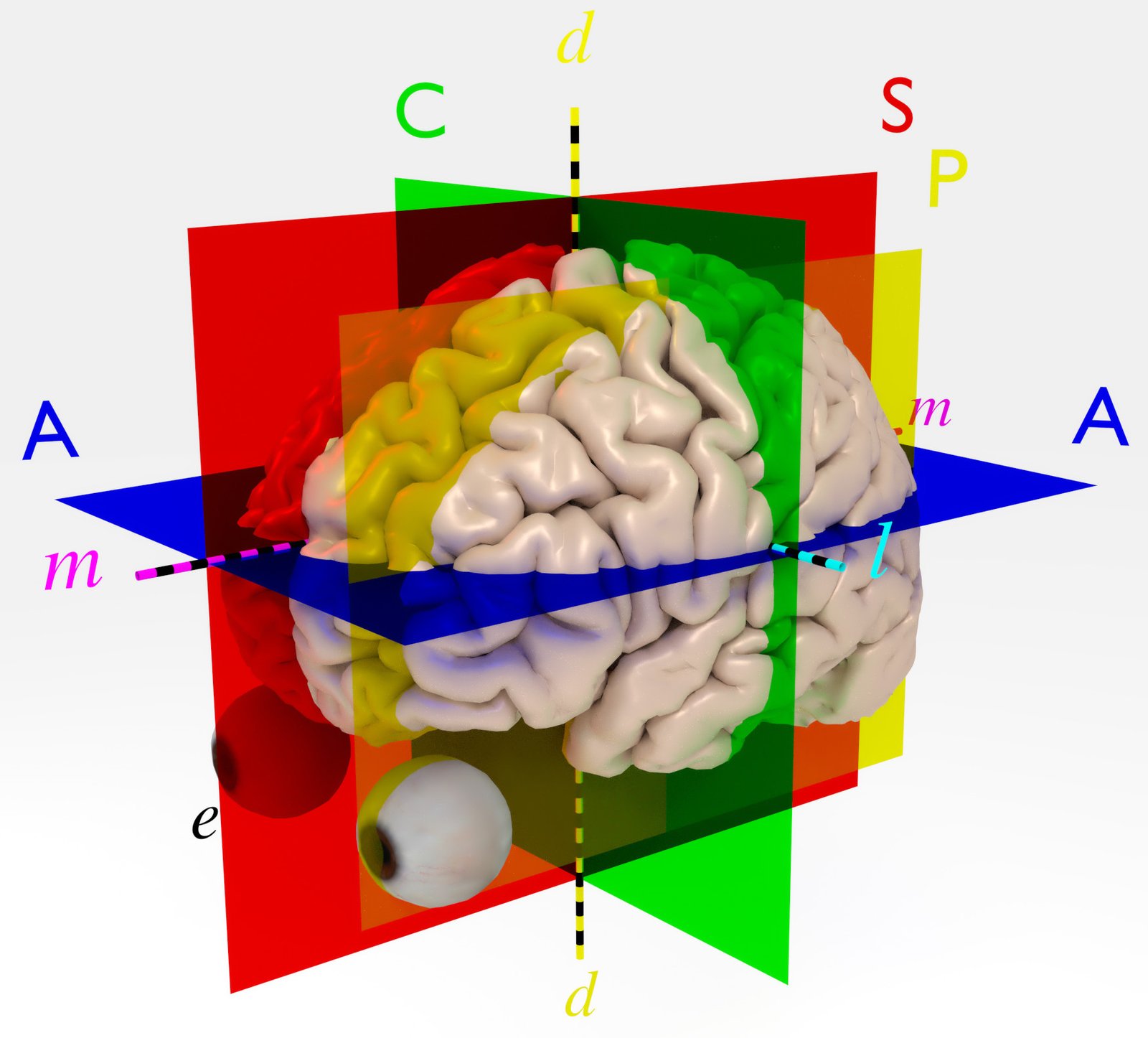

Language and the Human Brain

The human brain is uniquely wired for language. Areas like Broca’s and Wernicke’s regions, found in the left hemisphere, are critical for speaking and understanding language. Fossilized skulls can hint at brain size and shape, but they can’t show how these regions were used. Still, the expansion of the frontal lobe in Homo sapiens is often linked to our linguistic abilities. The way we process grammar, invent metaphors, and play with words may all spring from this ancient wiring.

Why Did Language Evolve?

Why did humans develop language at all? Some scientists believe it was for practical reasons—organizing hunts, warning of danger, or negotiating social alliances. Others think language was driven by a need to share stories, gossip, and emotions. Some even argue that love, jealousy, and humor shaped how we talk. The truth is probably a mix of all these forces, each one nudging early humans to communicate ever more clearly and creatively.

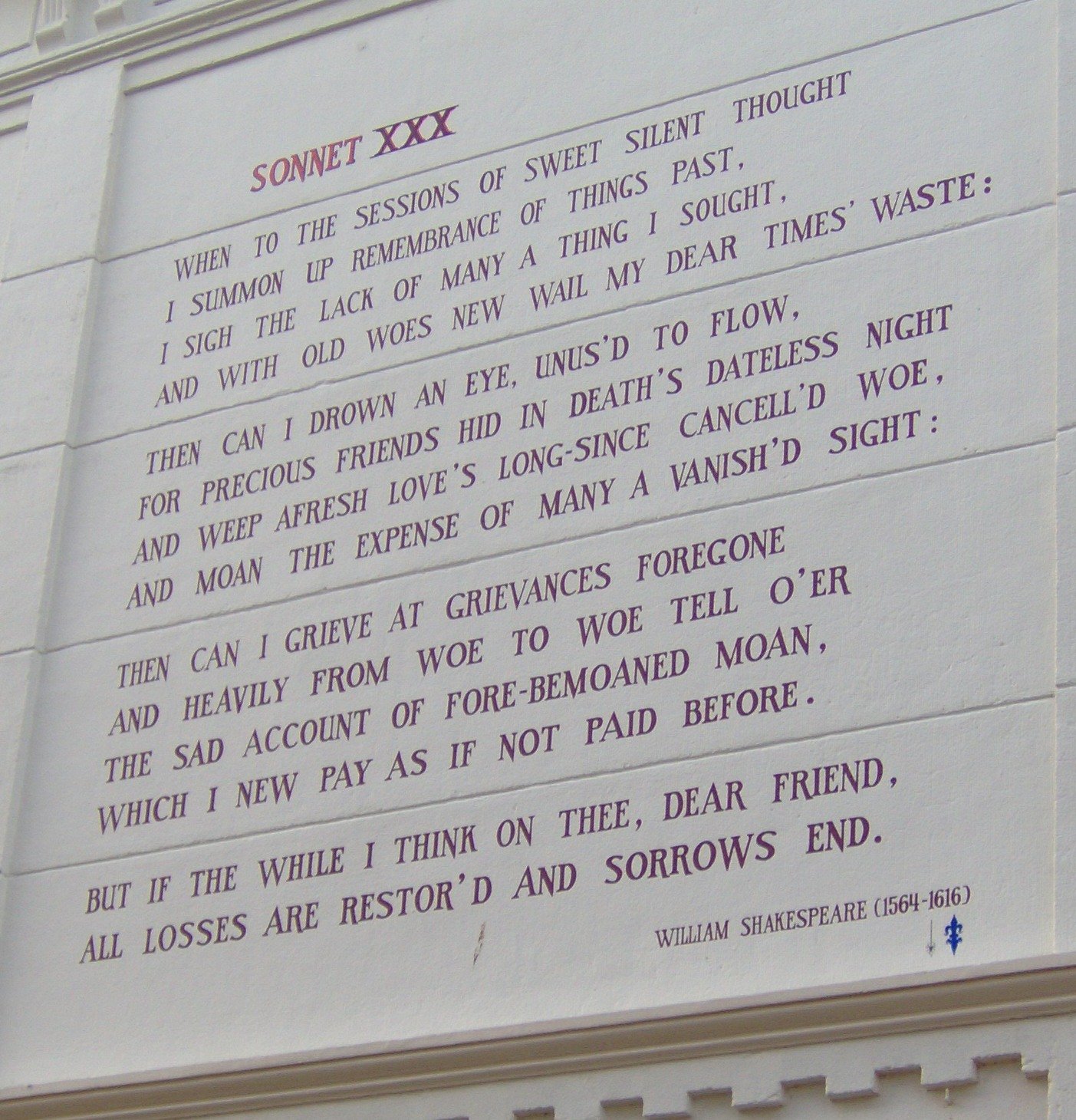

The Power of Storytelling

Storytelling is one of humanity’s oldest traditions. Around ancient fires, stories could teach, warn, or entertain—binding communities together. Linguists suggest that the urge to tell stories may have fueled the evolution of more complex language. The ability to weave events into a narrative helps people remember, plan, and imagine. Even today, a good story can move us to tears or laughter, connecting us back to those first storytellers under the prehistoric stars.

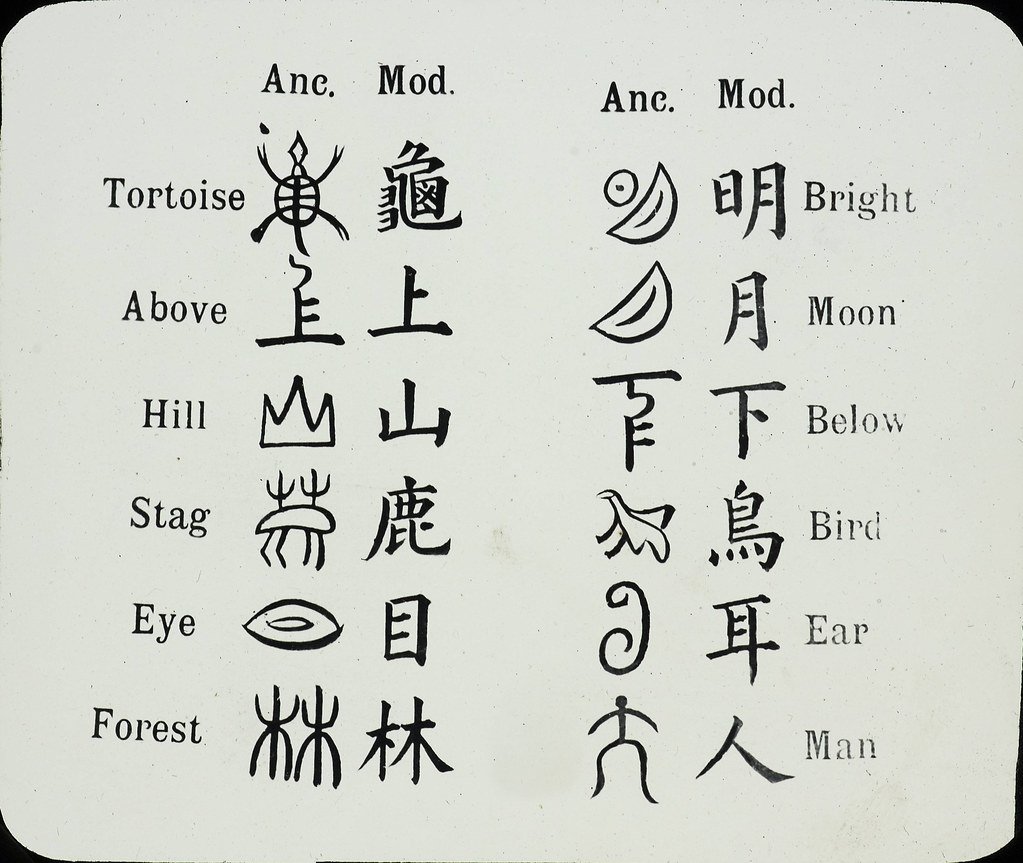

The Mystery of Lost Languages

Every language that exists today descends from older languages—many of which are now lost forever. Linguists call these “proto-languages,” but we can only guess at their sounds and structures. Some, like Proto-Indo-European, have been partly reconstructed, but prehistoric tongues that predate writing are mostly silent. It’s like trying to reconstruct a vanished city from a handful of bricks.

Modern Tools: Computational Linguistics and AI

Recently, researchers have started using computers and artificial intelligence to model how languages might have changed over time. By analyzing similarities and differences between modern languages, AI can help guess what ancient words might have sounded like. While these models are still in their infancy, they’re offering surprising new insights—and raising even more questions about the twists and turns of linguistic evolution.

Clues from Modern Hunter-Gatherers

Some linguists look at modern hunter-gatherer societies for clues about how prehistoric languages might have worked. These groups often have rich oral traditions and complex languages, even without writing. Studying their communication styles can give us a window into how language might have functioned in small, tightly knit communities—where everyone knew each other’s names, secrets, and dreams.

The Role of Children in Language Change

Children are natural language innovators. They constantly invent new words, simplify grammar, and reshape speech patterns. In prehistoric times, the way children learned and changed language may have been a powerful force in its evolution. Even today, children’s “baby talk” often echoes the kinds of simple, repetitive words that might have been common among our earliest ancestors.

What Animal Communication Teaches Us

Looking at how animals communicate can shed light on the origins of human language. Songbirds, whales, and even prairie dogs use complex vocalizations to warn, attract mates, or find food. Yet, animal “languages” lack the flexibility and creativity of human speech. These comparisons remind us that our ability to talk, argue, joke, and dream out loud is truly extraordinary—built on ancient foundations, but uniquely our own.

Language as a Social Glue

Language doesn’t just transfer information; it binds people together. The ability to share secrets, make promises, and resolve conflicts may have been just as important as hunting or gathering food. Some scientists believe that gossip—talking about who did what to whom—was a driving force in language evolution. In a way, language is the original social network, weaving individuals into families, tribes, and cultures.

How Language Still Evolves Today

Languages are living things; they grow, change, and sometimes die out. New words enter our vocabularies all the time—think of how “selfie” or “hashtag” appeared almost overnight. This constant evolution is a reminder that the forces shaping prehistoric languages are still at work today. Every conversation, every joke, every whispered secret is a tiny ripple in the vast ocean of human speech.

The Enduring Mystery and Why It Matters

Despite all our scientific advances, the origins of language remain one of humanity’s greatest mysteries. We may never know exactly what the first words were, or who spoke them. Yet, this mystery is part of what makes language so precious. It’s the invisible thread that ties us to our ancestors, to each other, and to everything we might become. Every time you speak, you add your own note to an ancient, ongoing song. Isn’t it wild to wonder what echoes might linger from those first voices, so long ago?