It’s a chilling thought: somewhere, perhaps not so long ago, the last true Indigenous polymath—someone who embodied the knowledge of healer, astronomer, storyteller, ecologist, and philosopher—took their final breath. In that moment, a living library closed its doors forever. Imagine a mind that carried centuries of wisdom, secrets of the forest, intricate mathematics of the stars, and the oral blueprints for living in delicate harmony with nature. What vanished with them? What elegant understandings and subtle languages dissolved into silence? The loss isn’t just a story of the past; it’s a wound that still aches in the present, echoing in the emptiness left by forgotten songs, vanished ceremonies, and lost ways of seeing the world. Let’s open this door together and step into what was left behind when the last Indigenous polymath left us—what humanity might never fully recover.

The Ancient Web of Knowledge

Indigenous polymaths were not specialists in a single field—they were masters weaving many threads into one tapestry. They knew how the plants grew, when the rains would come, and how to heal wounds using the secrets of roots and minerals. Their minds were like living encyclopedias, each chapter written by ancestors and updated through direct experience. Unlike modern scientists, who often work in isolated silos, these polymaths connected everything: stars, seeds, spirits, and survival. When they passed, whole systems of understanding—built over generations—were suddenly at risk of unraveling. It’s like losing not just one book, but an entire genre from the world’s library.

The Lost Language of the Land

Every landscape has its own language—one that only those who truly listen can understand. Indigenous polymaths spoke this language fluently. They could “read” the rustle of leaves to predict storms or recognize the subtle migration of animals as a sign of seasonal change. Their words for plants, animals, and places often carried meanings layered with stories, instructions, taboos, and humor. When their voices faded, so did these precise, poetic vocabularies. Today, many Indigenous languages are endangered, and with them, the unique ways of seeing and speaking about the world slip away—leaving gaps even the best dictionaries can’t fill.

Medicine Lost in the Shadows

Some of the world’s most potent medicines were first discovered by Indigenous healers—those same polymaths who could identify a leaf by taste or know which bark cured fevers. Their pharmacopoeia was not written down in textbooks but entrusted to memory and practice. When the last of these healers died without an apprentice, entire treatment protocols, holistic philosophies, and subtle diagnostic arts disappeared. Modern science is only now beginning to rediscover the value of these remedies, but often, the knowledge of how, when, and why to use them is already gone.

Cosmic Maps and Star Stories

Indigenous polymaths were astronomers without telescopes. They charted the heavens, named the constellations, and wove celestial events into the fabric of their lives. Their sky maps guided navigation, agriculture, and rituals. Unlike Western maps, which often separated stars from stories, Indigenous sky lore was vibrant and interactive—constellations became ancestors, animals, or moral lessons. With the loss of these storytellers, humanity lost not just technical knowledge but also a sense of wonder and belonging to the cosmos. Many of these star stories are now only fragments, scattered like stardust.

Ecological Wisdom and Balance

The last Indigenous polymath was a custodian of balance. They understood the rhythms of ecosystems—when to harvest, when to let the land rest, how to encourage abundance without tipping the scales. Their knowledge was rooted in observation, trial and error, and deep respect for all life. Today, as we face ecological crises, we realize just how much was forgotten: sustainable fishing techniques, fire management, and soil stewardship practices that kept landscapes thriving for millennia. Their memory serves as a haunting reminder that some of the best solutions may have already slipped through our fingers.

Mathematics in Nature’s Patterns

Patterns in shells, leaves, and rivers—Indigenous polymaths could see mathematical order where others saw chaos. They counted the phases of the moon, measured shadows to mark time, and could predict tides or animal migrations using complex algorithms passed down as stories or riddles. Their mathematics was practical, beautiful, and intimately tied to survival. When these living calculators disappeared, so did countless formulas and methods for understanding the world’s cycles—some of which have never been replicated or even recognized by modern mathematics.

The Art of Story and Memory

Stories weren’t just entertainment—they were libraries encoded in song, dance, and ritual. Polymaths were the keepers of these oral traditions, capable of reciting epic histories, genealogies, and practical knowledge with astonishing accuracy. Their memories held blueprints for building, farming, and healing, all disguised as tales of gods, heroes, and tricksters. When the last custodian of these stories died, much of this wisdom evaporated, leaving only fragments—like trying to assemble a puzzle with most of the pieces missing.

Sacred Geometry and Architecture

From the layout of villages to the construction of ceremonial sites, Indigenous polymaths applied sacred geometry—aligning structures with the movements of the sun, moon, and stars. These designs weren’t just functional; they were cosmological statements, blending science and spirituality. Without the original architects to explain the whys and hows, many ancient sites remain mysterious, their secrets locked behind patterns and purposes now forgotten. Modern archaeologists are still puzzled by these ingenious blueprints, which once guided entire communities.

Rituals of Healing and Harmony

Rituals were more than superstition—they were sophisticated systems for maintaining mental, physical, and communal health. Polymaths designed ceremonies that aligned human activity with natural cycles, using rhythm, song, and symbols to heal wounds both seen and unseen. They understood the psychological power of ritual, long before Western science coined the term “placebo effect.” With their passing, the nuanced understanding of how collective belief and symbolic action could transform reality faded into obscurity, leaving rituals as hollow echoes rather than living practices.

Ethics of Reciprocity and Respect

One of the most profound legacies of Indigenous polymaths was their ethical code—an understanding that every action ripples through the web of life. They taught reciprocity, respect, and restraint: take what you need, give back, and remember your place within the whole. This wasn’t just philosophy; it was a practical guide for survival. When their voices fell silent, so too did many of these guiding principles—replaced, in many places, by extractive mindsets with devastating consequences for both people and planet.

The Science of Senses

Polymaths trained their senses to levels most of us can hardly imagine. They could identify plants by scent alone, track animals by the faintest sound, and read subtle shifts in the wind or water. Their sensory skills weren’t magic—they were the result of lifelong practice and cultural training. With their departure, humanity lost a kind of embodied knowledge that can’t be taught in a classroom or written in a book. It’s the difference between reading about music and hearing it played live.

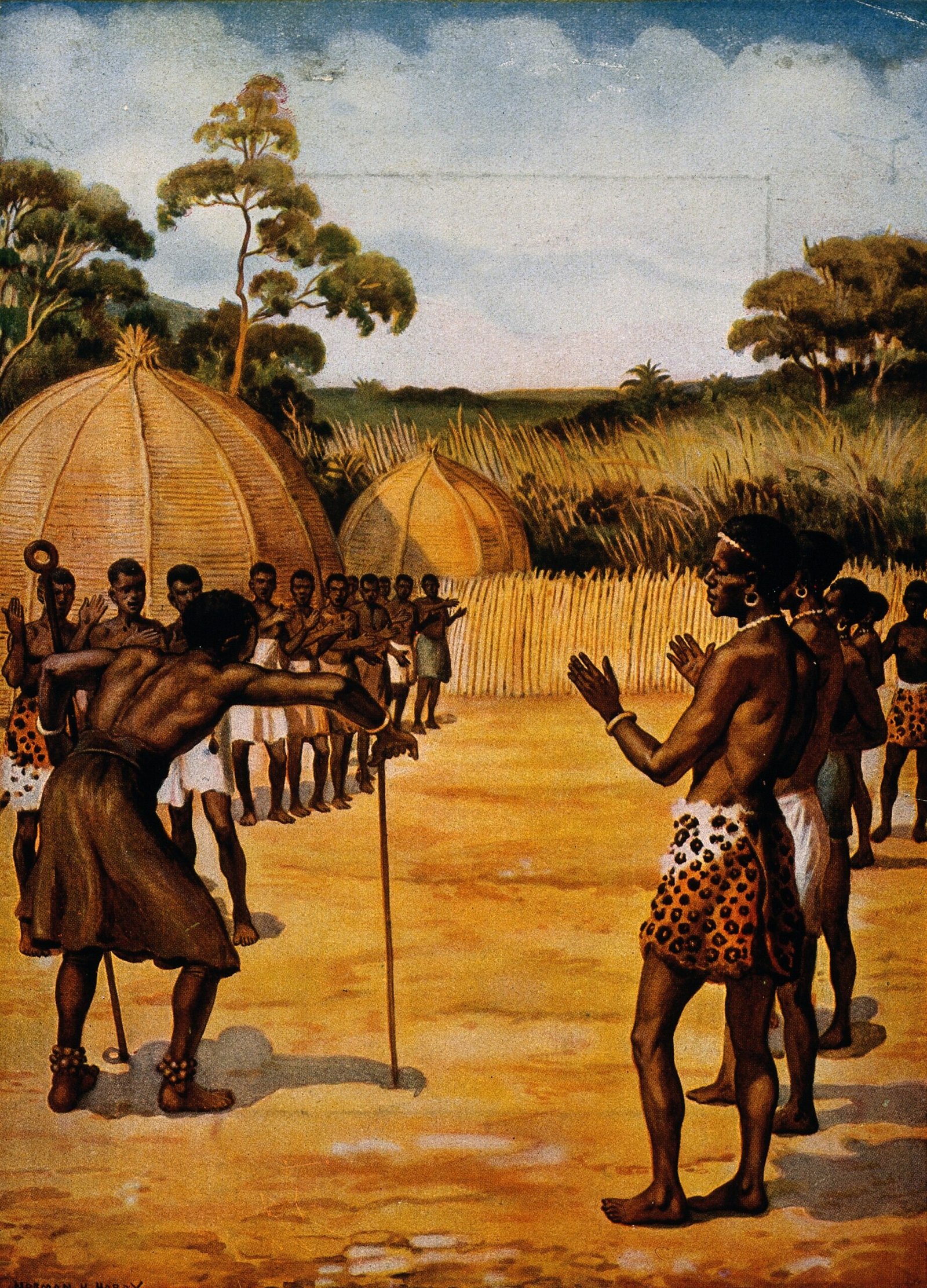

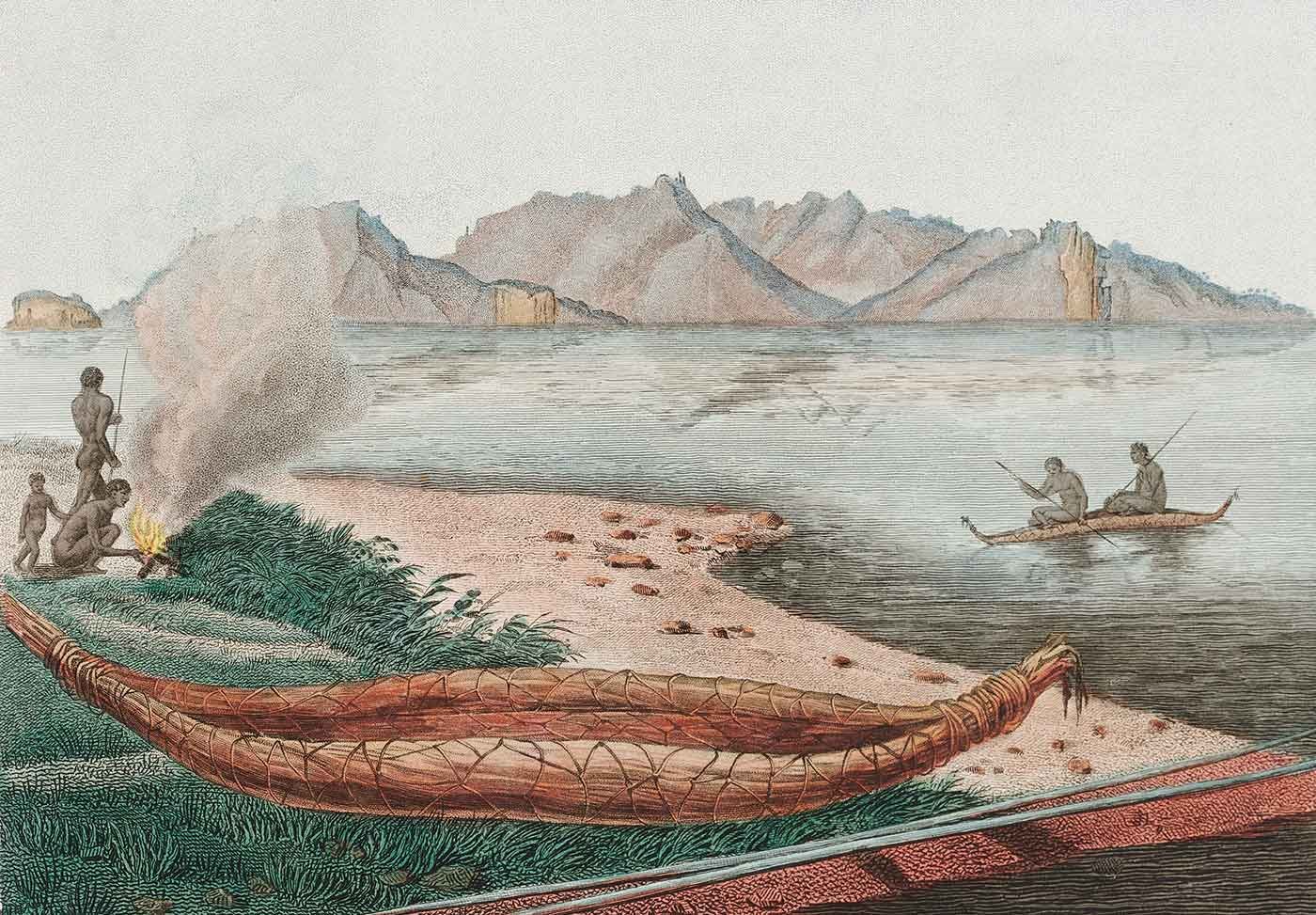

Languages of Gesture and Sign

Not all Indigenous knowledge was spoken. Many communities developed intricate sign languages and gesture codes, allowing them to communicate across distances or in silence during hunting. Polymaths were fluent in these visual vocabularies, using them to signal danger, organize hunts, or tell stories without words. As these experts vanished, so too did many of these unique “languages”—leaving behind only faint traces in old photos or fading memories.

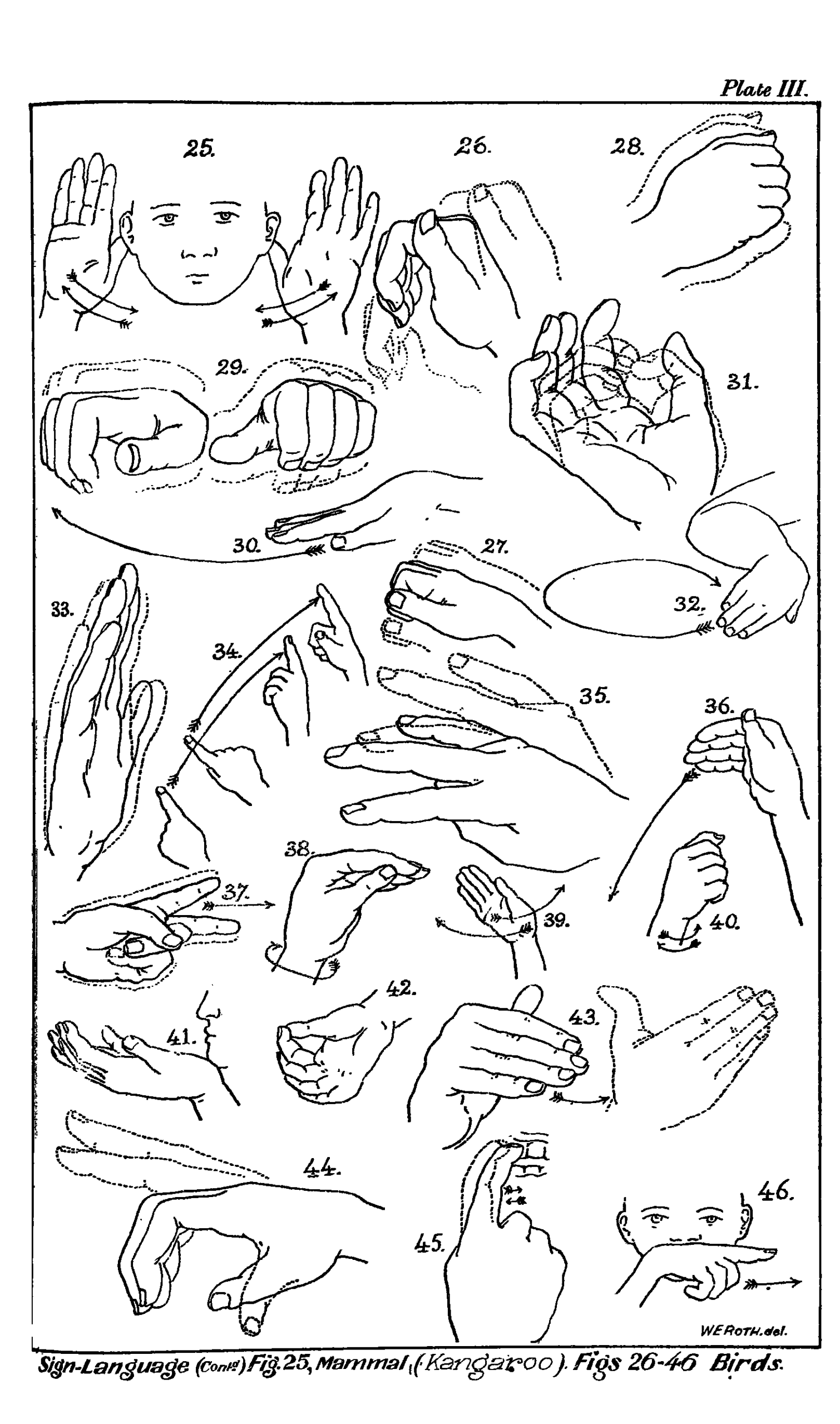

Mapping Without Maps

Imagine navigating dense forests or vast deserts without GPS, compass, or even paper maps. Indigenous polymaths could do just that, using mental maps built from stories, landmarks, and sensory cues. They taught others how to “read” the land—following the flight of birds, the taste of water, or the shape of distant hills. These mapping skills were crucial for survival and connection, yet many have been lost, leaving younger generations with only partial maps and uncertain paths.

Cultural Adaptation and Innovation

Polymaths weren’t just keepers of tradition—they were innovators, constantly adapting tools, practices, and beliefs to changing circumstances. They experimented with new crops, blended materials to craft better tools, and invented social systems that balanced risk and reward. Their creativity was a survival strategy in unpredictable environments. With their loss, many Indigenous communities faced greater challenges in adapting to rapid changes, from colonization to climate change, without the guiding hand of these adaptive thinkers.

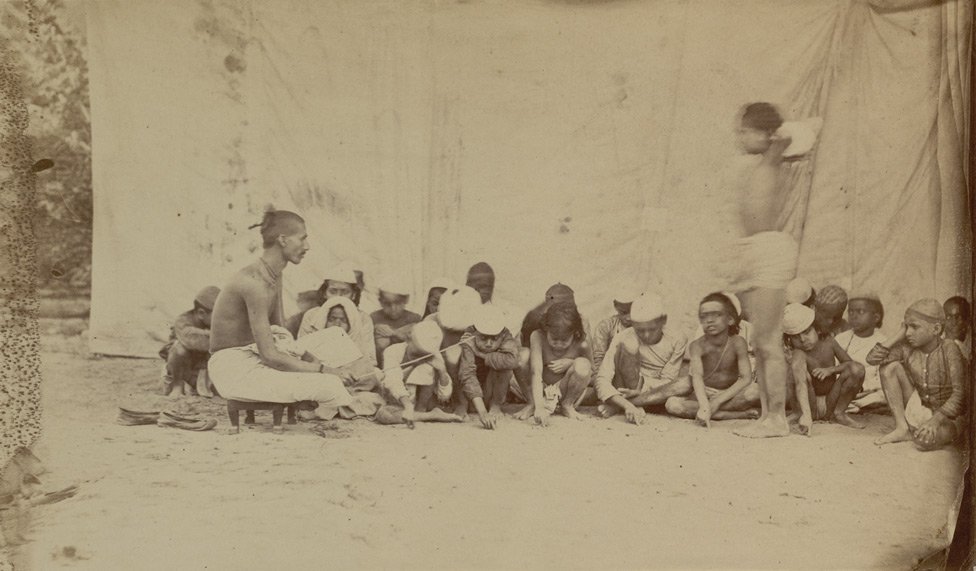

Teaching Without Schools

Education in Indigenous communities was hands-on, holistic, and lifelong. Polymaths were the main teachers—not through lectures, but by example, mentorship, and participation. They showed how to fish, how to read the weather, and how to interpret dreams. Their teaching methods fostered independence, observation, and respect for elders. When their voices faded, so did much of this living curriculum, and formal schools often struggled to fill the gap with the same depth and personal connection.

Spiritual Ecologies

For Indigenous polymaths, spirituality was inseparable from ecology. Every river, mountain, and animal had a spirit or story, and these relationships shaped how people behaved. They mediated between human and non-human realms, ensuring that rituals and offerings maintained balance. Without these spiritual stewards, many ecosystems lost their guardians, and people lost a sense of connection to the land that went deeper than ownership or utility.

Gender, Identity, and Social Roles

Polymaths often held unique social positions, challenging Western ideas about gender, leadership, and expertise. In many cultures, knowledge keepers could be women, two-spirit people, or elders whose authority came from wisdom, not hierarchy. Their disappearance sometimes meant the loss of more inclusive and flexible social systems—leaving behind rigid roles that didn’t fit the complexity of real human lives. The richness of these social fabrics is only now being rediscovered and celebrated.

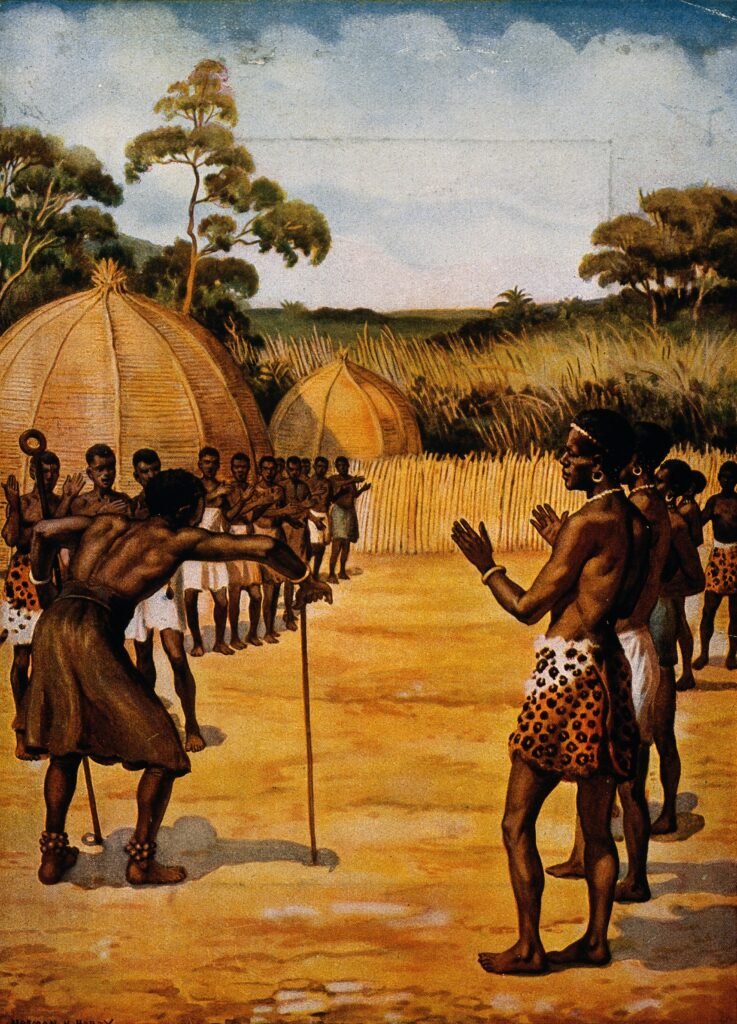

Conflict Resolution and Peacemaking

When disputes arose, Indigenous polymaths were often the mediators—drawing on deep knowledge of history, kinship, and law. Their peacemaking skills went beyond negotiation; they wove together stories, rituals, and shared experiences to heal rifts. With their passing, some communities lost traditional methods for resolving conflict, turning instead to external systems that didn’t always understand the local context.

Food Systems and Culinary Science

The diets of Indigenous peoples were shaped by polymaths who knew which plants were safe, how to process toxins, and when to harvest for maximum nutrition. They invented fermentation techniques, food storage methods, and recipes that balanced health with taste. When the last of these culinary scientists disappeared, so did many unique foods, flavors, and methods—along with the health benefits they provided. Modern diets often pale in comparison to the diversity and subtlety once present.

Resilience in the Face of Change

Perhaps the greatest gift of Indigenous polymaths was their resilience. They guided their people through droughts, floods, invasions, and epidemics—not just by preserving knowledge, but by knowing how and when to change. Their wisdom was a living thing, always growing and adapting. In their absence, many communities have struggled to maintain this resilience, facing unprecedented challenges with fewer tools and less guidance than before.

What Remains to Be Remembered?

When the last Indigenous polymath died, humanity lost more than a person—we lost a way of seeing, knowing, and being in the world. The memory of their wisdom lingers in fragments: a surviving song, a sacred site, a story half-remembered by a grandchild. The question is not just what we forgot, but what we are willing to remember, reclaim, and relearn. How much of this ancient brilliance still waits for us, hidden in plain sight, if only we choose to listen?