If you could look at a compass millions of years ago, the needle might have pointed south instead of north. That sounds like a science fiction plot twist, but it’s real: the Earth’s magnetic field has flipped many times throughout its history. These reversals are buried like secret fingerprints in ancient rocks, quietly telling the story of a restless, churning planet beneath our feet.

Most of us go through life assuming north is north and that’s that. Yet deep below the surface, the forces that generate our magnetic field are anything but stable. Understanding why the field flips, how often it happens, and what it does to life and technology is one of the most fascinating puzzles in Earth science today – and it has surprisingly direct implications for satellites, power grids, and even our ability to navigate the world.

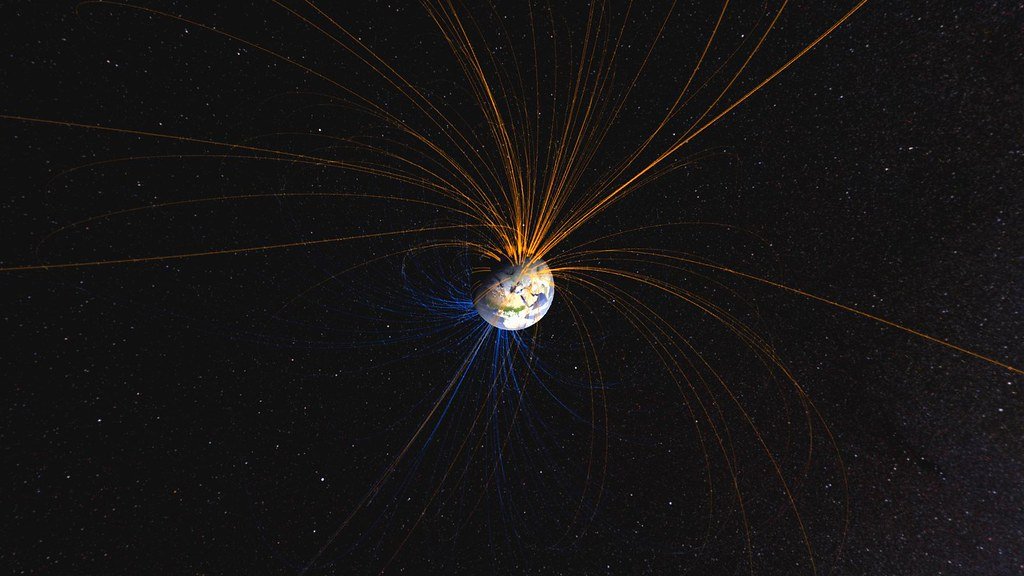

The Invisible Shield: How Earth’s Magnetic Field Is Generated

The Earth’s magnetic field starts far below our feet, in the outer core, a layer of molten iron and nickel roughly as hot as the surface of the Sun. This liquid metal is constantly in motion, stirred by heat escaping from the deeper inner core and by the planet’s rotation. You can think of it like a gigantic metal ocean, endlessly swirling, streaming, and spiraling.

Because iron is electrically conductive, those swirling motions generate electric currents, which in turn create magnetic fields. All of these overlapping magnetic fields combine into what scientists call the geodynamo: a self-sustaining system where motion creates magnetism, and magnetism feeds back on motion. From that chaos emerges something surprisingly simple at the surface – an overall field that looks roughly like a giant bar magnet, with magnetic north and south near the geographic poles.

The Turbulent Core: Why the Field Sometimes Flips

The big surprise is that this geodynamo isn’t locked into one configuration forever. The liquid outer core is turbulent, more like boiling water than a calm, steady flow. When the convective patterns in this molten metal change – because of heat flow variations, compositional differences, or long-term cooling – the structure of the magnetic field can become unstable. It stops behaving like a neat bar magnet and becomes tangled and patchy.

During some of these unstable periods, the large-scale field weakens significantly and then re-emerges with the opposite polarity. In other words, what we call magnetic north becomes magnetic south, and vice versa. The exact trigger is still an active research topic; simulations show that reversals can arise spontaneously from the chaotic behavior of the fluid core, even without a single dramatic event. It’s less like flipping a switch and more like a swirling storm reorganizing itself into a new pattern.

How Often Does Earth’s Magnetic Field Flip?

One of the strangest things about magnetic reversals is that they don’t follow a neat schedule. Geologists reconstruct past flips by studying volcanic rocks and seafloor crust, which lock in the direction of the magnetic field at the moment they cool and solidify. When scientists line up these records, they see a history of irregular reversals – sometimes separated by a few hundred thousand years, sometimes by tens of millions of years.

On average, the field reverses roughly every few hundred thousand years, but “average” is a bit misleading here. There was a long stretch, known as the Cretaceous Normal Superchron, when the field did not flip for nearly forty million years. The last full reversal, called the Brunhes–Matuyama reversal, happened around three-quarters of a million years ago, which means we’re not “overdue” in any strict sense. The system is chaotic, not clockwork, which makes predictions extremely uncertain.

What Actually Happens During a Magnetic Reversal?

A reversal is not an overnight catastrophe where compasses suddenly spin wildly one Tuesday morning. Based on rock records and computer models, a typical flip takes thousands to tens of thousands of years to complete. During that time, the global dipole field weakens, and the magnetic structure becomes much more complicated, with multiple north and south poles appearing in different regions. At the surface, this would show up as erratic, shifting directions for a compass, depending on where you stand.

As the field weakens, more of the magnetic protection comes from smaller, regional fields rather than one strong global dipole. The overall shielding from cosmic radiation and charged particles can drop, although pockets of strong local field may persist. Eventually, the system settles into a new configuration, with the large-scale field re-establishing itself – just with its polarity reversed. To anyone living through it, the changes would be extremely slow on a human timescale, more like watching continents drift than witnessing a sudden flip.

Impact on Life: Do Magnetic Flips Cause Mass Extinctions?

When people first learn that Earth’s shield can weaken dramatically during reversals, it’s natural to imagine apocalyptic consequences for life. So far, the fossil record does not support that fear. There is no clear pattern connecting magnetic reversals to mass extinctions or sudden global die-offs. Life has persisted through countless reversals over billions of years, adapting to a planet whose magnetic environment is more flexible than we might think.

That said, some organisms do rely on the magnetic field for navigation, such as migratory birds, sea turtles, certain fish, and even some insects. During a reversal, these species might face confusing, shifting cues, which could disrupt migration routes or breeding habits. But nature tends to be surprisingly adaptable – many animals combine magnetic information with stars, smells, landmarks, and other signals. Instead of a global biological crisis, the evidence points toward gradual adjustments and localized stress rather than a planet-wide catastrophe.

For humans, the main biological concern would be an increase in harmful radiation reaching the atmosphere as the field weakens, especially near the poles. However, the atmosphere itself still provides a significant shield, and any changes would unfold slowly. There could be a modest rise in radiation-related health risks at high latitudes, but not an instant, movie-style disaster. The bigger challenges for us are not our bodies, but our technologies.

Modern Technology Under Stress: Satellites, Power Grids, and Navigation

Our technological systems are tightly linked to the behavior of the magnetic field, often in ways we barely notice until something goes wrong. Satellites, for example, orbit within regions influenced by charged particles trapped by Earth’s magnetic field. When that field weakens or shifts, more energetic particles can penetrate into orbits where communication, navigation, and weather satellites operate. That can damage electronics, shorten satellite lifetimes, and cause more frequent outages.

Down on the ground, power grids are also vulnerable. Solar storms already induce electric currents in long power lines by interacting with the magnetosphere. If the global field is weaker or more irregular, the atmosphere and near-Earth space could be more exposed to solar eruptions, making strong geomagnetic storms more common or more intense. The result can be transformer damage, blackouts, and expensive repairs. On top of that, navigation systems – from simple compasses to some backup modes in ships and aircraft – depend on a stable map of magnetic north. During a reversal, those maps would need constant updating, and many industries would lean even more on satellite-based systems like GPS, which have their own radiation vulnerabilities.

Are We Heading Toward the Next Flip – and Should We Worry?

Measurements over the last two centuries show that Earth’s magnetic field is currently weakening, especially in an area known as the South Atlantic Anomaly, where the field is unusually weak and satellites often experience glitches. Some researchers see this as a possible early sign of a long-term reorganization of the geodynamo, maybe even a precursor to a future reversal. Others argue it could simply be part of the normal, wandering behavior of a complex system, not necessarily the start of a flip. The truth is, with only a short window of direct measurements, we’re trying to infer long-term behavior from a tiny snapshot in time.

From what we know today, a future reversal would be disruptive but not world-ending. The main risks involve space weather, infrastructure resilience, and our overreliance on vulnerable technology. In practical terms, that means better shielding for satellites, smarter grid design, and ongoing monitoring of the field using ground observatories and satellites. Personally, I find it oddly comforting: the planet has been flipping its magnetic field for eons, and life has kept going. The real question is whether we’ll use what we know now to prepare our modern systems for an old, recurring feature of Earth’s restless heart.