In the heart of Utah’s high desert, a sun-bleached ridge hides a puzzle that has nagged at paleontologists for generations. How did so many dinosaurs – especially big predators – end up tangled together in one place, their bones jumbled like driftwood after a storm? The site, anchored by the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry within Utah’s Jurassic National Monument, is more than a bonebed; it’s a time capsule from a world roughly one hundred and fifty million years in the past. New tools and fresh eyes are transforming this famous graveyard from a mystery into a laboratory, where each fragment adds another clue. The story that’s emerging is dramatic, messy, and far more revealing than anyone expected.

The Hidden Clues

What kind of place produces more carnivore bones than herbivores – and in such staggering numbers? The layers here read like a crime scene report, with disarticulated skeletons, tooth-scored ribs, and bones sorted by water and mud. The sheer density is shocking, yet the patterning is oddly consistent, as if the landscape itself was funneling animals toward a deadly trap.

Researchers treat every bone as a data point: where it lay, how it broke, what microscopic scratches say about transport and scavenging. A femur polished smooth suggests repeated jostling in a wet, shifting mire; a cluster of juvenile bones hints at age-specific behavior or an ecological imbalance. Seen together, these clues point to a dynamic floodplain that could flip from dusty drought to sticky, lethal ooze in a single season.

A Quarry with a Story

Utah’s “graveyard” sits in rocks of the Morrison Formation, a ribbon of Late Jurassic mudstones and sandstones that underpins some of the world’s most iconic dinosaur finds. Over many decades, crews pulled thousands of bones from this quarry, and a striking share belong to the apex predator Allosaurus. The place feels haunted by teeth and claws, yet traces of plant-eaters – stegosaurs, long-necked sauropods, and their kin – thread through the mix like bass notes in a heavy song.

The first time I hiked the outcrop, the wind carried a fine grit that settled into my notebook, the way dust settles into crevices of time. It’s not a neat museum diorama; it’s a story of struggle written in mud. Every trench dug and layer mapped has reshaped the narrative, turning a local curiosity into a world-class case study in how ecosystems collapse and rebuild.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

Early crews worked with shovels, plaster jackets, and patience, shipping bones to museums where they’d be cleaned and cataloged by hand. Today, drones stitch aerial mosaics so precise that researchers can measure bone orientations down to degrees, while photogrammetry renders trench walls as navigable 3D models. Micro-CT scans reveal hidden fracture patterns, and thin-section histology reads growth rings in bone like tree rings, teasing out life histories.

Geochemists sample sediments and bone apatite to reconstruct water chemistry, seasonality, and even the turbidity of ancient ponds. Zircon crystals in ash layers can be dated with remarkable accuracy, anchoring events in time instead of leaving them to guesswork. The result is a high-resolution picture of death, decay, and burial that outstrips what any field notebook alone could deliver.

The Debate: Predator Trap or Drought Disaster?

The classic story says the site was a predator trap – a mud-churned waterhole that snagged meat-eaters lured by carcasses, dooming hunter after hunter. An alternative sees a drought-busted landscape where thirsty herds crowded shrinking ponds, followed by a violent storm that turned the basin into quicksand. Both fit parts of the evidence; neither fully explains everything, including the age profiles and the unusually high tally of carnivores.

New modeling blends the scenarios: seasonal drying concentrates animals; storms spike runoff; mud and shallow pools create zones where a stumble becomes fatal. Scavengers arrive in waves, adding more bodies and more bite marks, while currents and trampling fragment skeletons beyond easy recognition. In this hybrid view, tragedy wasn’t a single event but a repeating pattern baked into the landscape’s rhythm.

Global Perspectives

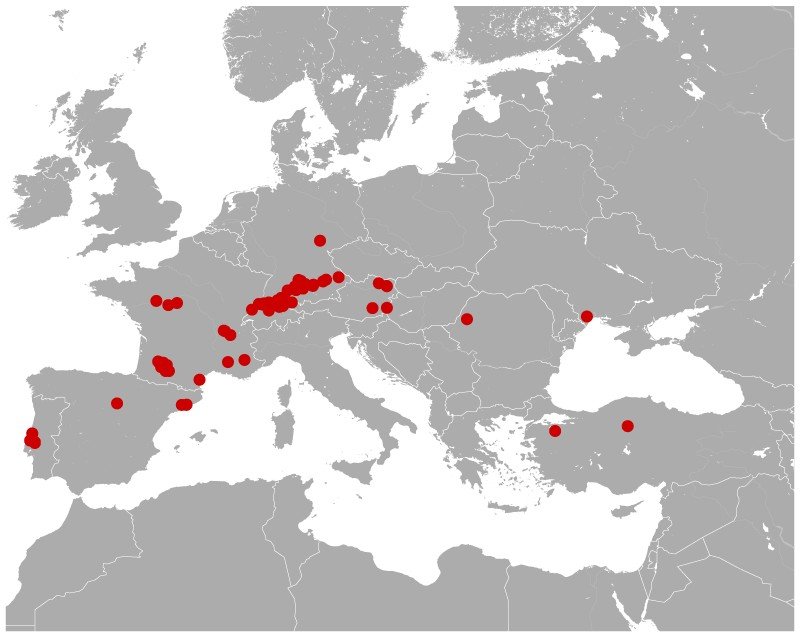

Utah’s graveyard doesn’t stand alone; it’s part of a global patchwork of Jurassic bonebeds from Portugal to China that capture ecosystems in various states of boom and bust. Some sites record catastrophic floods that entombed whole groups at once, while others show slow, attritional accumulation across seasons. By comparing species lists, bone weathering, and sediment fingerprints, scientists can test whether these deposits share the same script or reflect local quirks.

Patterns are emerging: predator-heavy sites often coincide with stagnant water and fine clays; better-oxygenated settings preserve more articulated skeletons and fewer tooth-scratched surfaces. Utah’s quarry sits near the predator-heavy end of that spectrum, making it a critical reference point. When researchers stack these datasets side by side, they’re not just naming dinosaurs – they’re mapping ancient risk on a continental scale.

Why It Matters

Bonebeds like this are time machines for ecology, not just showcases for spectacular skulls. They let scientists estimate life stages, growth rates, and the ebb and flow of populations across wet and dry years, which is impossible to glean from a single pristine skeleton. They also challenge traditional narratives, such as tidy predator-prey ratios that rarely match the messy realities of nature.

There’s a modern echo here: landscapes today swing between flood and drought, and animals still cluster around shrinking water. By decoding how Jurassic ecosystems responded to stress, researchers gain context for how communities reorganize under pressure. It’s not that the past predicts the future, but it sharpens our questions and makes our models more honest.

The Future Landscape

Next-generation surveys will knit together satellite imagery, drone photogrammetry, and ground-penetrating radar to map bonebeds without turning every rock. Machine-learning tools already help classify bone fragments, sort tooth marks from rock scratches, and flag patterns a tired brain might miss after a long day in the field. More refined geochronology promises tighter timelines, turning “somewhere in the Late Jurassic” into a sequence of seasons and storms.

There’s also a push for open 3D archives – freely navigable quarries and digital bones that researchers and students can examine from anywhere. Non-invasive chemical techniques are improving, reducing the need for destructive sampling while pulling richer signals from tiny grains. The biggest challenge is synthesizing these torrents of data into coherent stories, so that the graveyard continues to teach rather than simply dazzle.

The Hidden Clues, Revisited on the Ground

Walk the quarry in late afternoon and the sun picks out the subtle textures: ripple marks of an ancient shoreline, a smear of bone bedded in chocolate-colored clay, a thin lens of ash like frost. Those details ground the high-tech reconstructions and keep interpretations honest. You can feel the place’s energy – restless, hungry, and indifferent – just as it must have felt to the animals that risked a drink there.

Field teams still map by hand, still argue over trench walls, still celebrate the small victories when a fragment clicks perfectly into its neighbor. That blend of grit and precision is the engine of discovery. Even with all our tools, progress comes bone by bone, layer by layer, until the ancient scene stops being abstract and starts feeling real.

A Simple Call to Action

If this story moved you, there are easy ways to help preserve and advance it. Visit public fossil sites and museums, ask questions, and support programs that fund student fieldwork and curation; the unglamorous work of cataloging ensures discoveries aren’t lost in storage. When you hike in fossil-rich country, look but don’t pocket; report finds to land managers so specimens keep their scientific context. Advocate for responsible land stewardship that balances access with protection, because once a site is looted or eroded away, its data are gone for good.

I keep a small habit on field trips: I write down one question the rocks made me ask that day, then I try to chase it. You can do the same from home – follow ongoing digs, explore digital bonebeds, and share the science with someone who’s never heard of a predator trap. The past is still speaking out there in the heat shimmer, and we’ll hear it better if more of us lean in. What question will you chase next?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.