Imagine walking through a moonlit garden where every plant whispers secrets of healing and magic. For centuries, herbalists and healers have tended gardens filled with mysterious plants that blur the line between medicine and mysticism. These weren’t fairy tales or Hollywood fiction – they were real practitioners working with botanical knowledge that modern science is only beginning to fully understand. The same herbs that once filled bubbling cauldrons now stock our medicine cabinets, proving that sometimes the most compelling magic is simply good science waiting to be discovered.

Belladonna: Beauty’s Deadly Secret

Few plants carry as dark a reputation as belladonna, the “beautiful woman” whose name comes from Renaissance ladies who used its extracts to dilate their pupils for a more alluring appearance. Medieval witches supposedly used this deadly nightshade in flying ointments, creating hallucinogenic experiences that may have inspired tales of broomstick flights. The plant contains powerful alkaloids like atropine and scopolamine that can cause vivid hallucinations, delirium, and death in higher doses. Modern medicine has harnessed these same compounds for legitimate purposes – atropine is used to treat certain heart conditions and as an antidote for nerve agent poisoning. Eye doctors still use atropine drops to dilate pupils during examinations, proving that beauty and medicine sometimes share the same dangerous roots.

Mandrake: The Screaming Root of Power

The mandrake root, with its human-like shape, was perhaps the most feared plant in the witch’s arsenal. Legend claimed it would shriek when pulled from the earth, killing anyone who heard its cry. Medieval texts describe elaborate rituals for harvesting mandrake, often involving dogs tied to the plant to avoid the harvester’s doom. The root was prized for love potions, fertility spells, and as a powerful narcotic. Today, we know mandrake contains tropane alkaloids similar to belladonna, making it genuinely dangerous in untrained hands. Modern pharmaceutical research has isolated compounds from mandrake species for potential use in treating motion sickness and as muscle relaxants during surgery. The plant’s reputation for enhancing fertility might have some basis in its ability to relax smooth muscle tissue, though scientists advise against any home experiments.

Foxglove: Heart Medicine from Fairy Gardens

Foxglove towers in cottage gardens like purple spires reaching toward heaven, but this beautiful plant harbors potent cardiac glycosides that have both killed and saved countless lives. Folk healers called it “fairy’s glove” and used it cautiously for heart troubles, though the margin between healing and poisoning was razor-thin. Witches supposedly used foxglove in potions meant to influence matters of the heart – literally and figuratively. The breakthrough came in 1785 when physician William Withering documented foxglove’s effects on dropsy, a condition we now know as congestive heart failure. Modern medicine still relies on digitalis compounds derived from foxglove to treat certain heart rhythm disorders. The plant remains so potent that a single leaf can be fatal if ingested, reminding us that the line between poison and medicine often depends entirely on dosage.

Mugwort: The Dreamer’s Herb

Mugwort grows wild along roadsides and abandoned lots, yet this humble weed was once considered one of the most magical plants in the herbal world. Medieval practitioners burned mugwort to cleanse spaces of negative energy and stuffed pillows with its silvery leaves to encourage prophetic dreams. The herb was essential in “flying ointments” alongside more dangerous plants, possibly providing a mild psychoactive base that enhanced the effects of other ingredients. Modern research has identified compounds in mugwort that can indeed affect the nervous system, including thujone, which may influence dream intensity and recall. Some contemporary herbalists still use mugwort tea to promote vivid dreams, though they’re careful about dosage since thujone can be toxic in large amounts. The plant also shows promise in treating digestive issues and menstrual irregularities, validating some of its traditional uses.

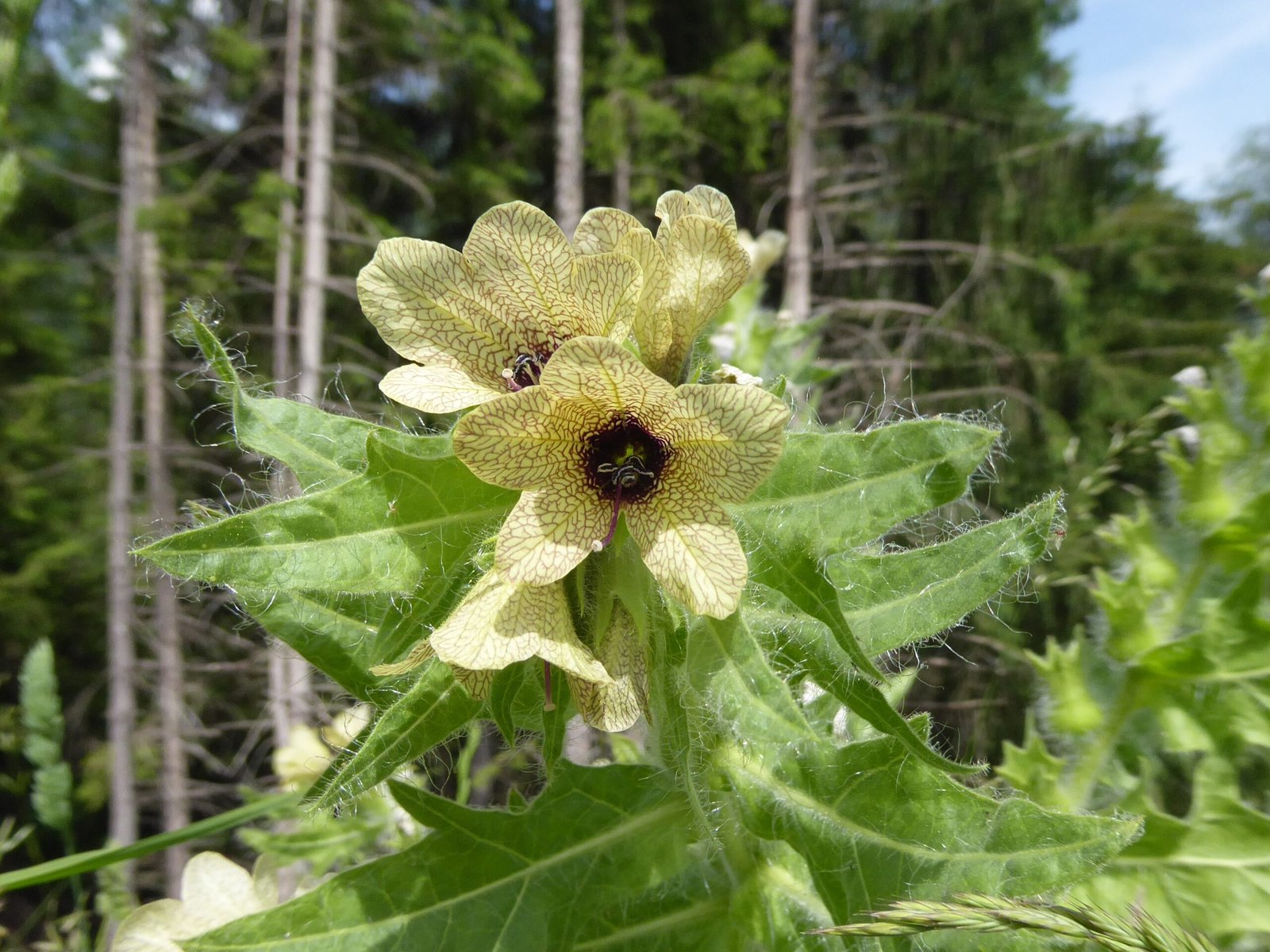

Henbane: The Sorcerer’s Sleep

Henbane earned its sinister reputation honestly, containing some of the most potent psychoactive compounds in the plant kingdom. Ancient texts describe its use in oracular ceremonies, where priests would inhale its smoke to enter trance states and communicate with gods. Medieval witches incorporated henbane into sleeping potions and truth serums, taking advantage of its ability to cause vivid hallucinations and lower inhibitions. The plant contains hyoscyamine and scopolamine, compounds that interfere with the nervous system in ways that can seem supernatural to observers. Modern medicine has found legitimate uses for these alkaloids in treating motion sickness, Parkinson’s disease, and as pre-anesthetic sedatives. Interestingly, scopolamine has been studied for its potential in treating severe depression, though its dangerous side effects limit clinical applications.

Wormwood: The Green Fairy’s Bitter Gift

Wormwood’s silvery-green leaves have flavored everything from ancient medicines to the notorious liqueur absinthe, earning it a reputation as both healer and destroyer. Medieval herbalists used wormwood to expel intestinal parasites, leading to its common name, while others incorporated it into protective charms and purification rituals. The plant contains thujone, a compound that can cause hallucinations and seizures in large doses – effects that contributed to absinthe’s ban in many countries during the early 1900s. Modern research has validated wormwood’s antiparasitic properties, with artemisinin compounds from related Artemisia species becoming essential antimalarial drugs that save millions of lives annually. The plant also shows promise in treating certain cancers and digestive disorders, though its psychoactive properties require careful monitoring in any therapeutic application.

Hemlock: Philosophy’s Final Lesson

Poison hemlock holds the dubious honor of being both one of history’s most famous execution methods and a surprisingly useful medicinal plant when properly prepared. This tall, spotted plant killed Socrates in ancient Athens and provided medieval poisoners with a reliable, relatively painless method of murder. However, skilled herbalists also used tiny amounts of hemlock to treat severe pain, muscle spasms, and epilepsy. The plant contains coniine and other alkaloids that paralyze the nervous system, starting with the extremities and working toward the vital organs. Modern pharmacology has largely replaced hemlock with safer alternatives, but researchers continue studying its compounds for potential applications in treating neurological conditions. The plant serves as a stark reminder that the difference between medicine and poison often lies not in the substance itself, but in the knowledge and intention of the person wielding it.

Datura: The Devil’s Trumpet

Datura’s trumpet-shaped flowers bloom at night, releasing an intoxicating fragrance that masks the plant’s deadly nature. Known by names like devil’s trumpet and jimsonweed, this plant has been used by shamans and witches across cultures for its powerful hallucinogenic properties. The entire plant contains tropane alkaloids that cause intense, often terrifying visions that can last for days. Unlike other psychoactive plants, datura’s effects are unpredictable and frequently dangerous, leading to accidental poisonings throughout history. Modern emergency rooms still treat datura poisoning cases, usually involving teenagers who underestimate its potency. However, pharmaceutical companies have isolated scopolamine from datura species for use in motion sickness patches and certain surgical procedures. The plant reminds us that not all traditional medicine translates safely to casual use – some knowledge requires genuine expertise and extreme caution.

Vervain: The Magician’s Crown

Vervain might look like an unremarkable roadside weed, but this humble plant was once considered so powerful that it was called “herb of the cross” and “tears of Isis.” Ancient Romans and Celts used vervain in religious ceremonies, believing it could ward off evil spirits and enhance magical workings. Medieval witches incorporated vervain into love potions and protection spells, while Christian mystics associated it with divine power. The plant contains compounds called iridoid glycosides that have mild sedative and anti-inflammatory effects, which might explain its reputation for bringing peace and healing. Modern herbalists use vervain to treat anxiety, insomnia, and nervous tension, finding that its gentle effects can indeed promote the calm, centered state that ancient practitioners attributed to magical properties. Recent studies suggest vervain might also have neuroprotective qualities, potentially supporting brain health as we age.

Rue: The Herb of Grace and Regret

Rue’s bitter taste and pungent smell earned it the nickname “herb of grace,” though its uses often involved anything but graceful purposes. Medieval texts describe rue as essential for protection against witchcraft, leading to its cultivation in monastery gardens and around homes. However, the same plant was also used by wise women to prevent or terminate unwanted pregnancies, making it both blessed and cursed in the eyes of different communities. Rue contains compounds that can indeed affect reproductive health, though in dangerous and unpredictable ways that have caused many poisonings throughout history. Modern research has identified anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties in rue, leading to its investigation as a potential treatment for certain skin conditions and bacterial infections. The plant’s dual reputation as protector and destroyer reflects the complex relationship between traditional plant medicine and the social structures that attempt to control it.

Yew: Death’s Evergreen Guardian

Ancient yew trees, some over a thousand years old, stand sentinel in churchyards across Europe, their evergreen branches symbolizing eternal life while their berries offer death to the unwary. Celtic druids considered yew sacred, using its wood for magical staves and incorporating its needles into potions meant to communicate with the otherworld. The entire tree except for the berry flesh contains taxine alkaloids that cause rapid cardiac arrest – a property that made yew both feared and strategically useful in ancient warfare. Modern medicine has turned yew’s deadly reputation to healing purposes, extracting paclitaxel from Pacific yew bark to create one of the most effective chemotherapy drugs for treating breast, ovarian, and lung cancers. This transformation from symbol of death to weapon against cancer represents one of the most dramatic reversals in the history of plant medicine, proving that even the most feared plants might hold keys to healing.

Wolfsbane: The Werewolf’s Bane

Wolfsbane, or monkshood, rises in tall spikes of deep blue flowers that hide one of nature’s most potent neurotoxins. Medieval legends claimed that wolfsbane could both create and cure lycanthropy – the transformation into werewolves – while poisoners throughout history have used its roots to eliminate enemies with symptoms that mimic heart attacks. The plant contains aconitine, a compound so toxic that simply handling the fresh plant without gloves can cause numbness and heart irregularities. Traditional Chinese medicine has used processed aconitine for centuries to treat chronic pain, though the preparation process requires extreme expertise to reduce toxicity while preserving therapeutic effects. Modern researchers are investigating synthetic versions of aconitine compounds as potential local anesthetics and treatments for certain types of chronic pain. The plant’s fearsome reputation seems well-deserved, yet its potential medical applications remind us that nature’s most dangerous gifts sometimes offer the most powerful healing.

Elder: The Mother Tree’s Medicine

The elder tree occupies a unique position in folklore as both protector and portal to the spirit world, with traditions warning against cutting elder wood without permission from the Elder Mother who dwells within. While less sinister than other witch’s herbs, elder played crucial roles in folk magic, with its flowers used for blessing rituals and its berries for divination practices. The tree’s hollow stems were fashioned into wands and flutes, while its bark and leaves provided medicines for everything from headaches to heart troubles. Modern science has validated many traditional uses of elder, finding that elderberries contain powerful antioxidants and compounds that can reduce the duration and severity of cold and flu symptoms. Elderflower preparations show anti-inflammatory properties and may help with respiratory conditions. The tree’s transformation from magical guardian to mainstream medicine illustrates how ancient wisdom and modern research can work together to improve human health.

Hellebore: Winter’s Dark Bloom

Hellebore blooms in the depths of winter when most plants lie dormant, earning names like Christmas rose and Lenten rose for its defiant beauty in the face of cold and darkness. Ancient Greeks used hellebore to treat madness and epilepsy, believing its bitter compounds could purge evil spirits from afflicted minds. Medieval physicians continued this practice, though they recognized the plant’s dangerous nature – hellebore poisoning could easily kill rather than cure. The plant contains cardiac glycosides similar to those in foxglove, affecting heart rhythm and potentially causing delirium, convulsions, and death. Modern medicine has moved away from hellebore due to its unpredictable toxicity, though researchers continue studying its compounds for potential applications in treating certain neurological conditions. The plant serves as a reminder that ancient healers often worked with incredibly dangerous substances, using empirical knowledge passed down through generations to walk the narrow line between healing and harm.

Pennyroyal: The Mint with a Dark Side

Pennyroyal looks innocent enough, resembling its mint family cousins with small purple flowers and aromatic leaves, but this herb has one of the most controversial histories in folk medicine. Ancient Greek and Roman women used pennyroyal to regulate menstrual cycles and prevent unwanted pregnancies, leading to its widespread cultivation despite growing awareness of its dangers. Medieval herbalists incorporated pennyroyal into various preparations, though they warned against its use by pregnant women. The plant contains pulegone, a compound that can cause severe liver damage, kidney failure, and death even in relatively small amounts. Modern toxicology has confirmed that pennyroyal essential oil is extremely dangerous, leading to numerous poisoning cases and deaths among people attempting to use it for its traditional purposes. While some herbalists still recommend mild pennyroyal tea for digestive issues, most experts advise avoiding this plant entirely due to its unpredictable toxicity and the availability of safer alternatives.

Tobacco: Sacred Smoke and Addiction

Long before tobacco became synonymous with addiction and disease, indigenous peoples of the Americas considered it one of their most sacred plants, using it in ceremonies to communicate with spirits and ancestors. Shamans would blow tobacco smoke over patients to drive away evil influences, while warriors used it to prepare for battle and hunters to ensure successful hunts. European colonists initially embraced tobacco as a miracle cure for everything from headaches to plague, not understanding its addictive properties or long-term health effects. The plant contains nicotine, a powerful alkaloid that affects the nervous system in complex ways, providing both stimulation and relaxation depending on dosage and individual response. Modern medicine has found legitimate uses for nicotine in treating certain neurological conditions, including potential applications for Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, though these are delivered through controlled pharmaceutical preparations rather than smoking. The transformation of tobacco from sacred medicine to public health crisis illustrates how cultural context and method of use can dramatically alter a plant’s impact on human society.

Mistletoe: Love and Death in the Sacred Grove

Mistletoe grows as a parasitic plant high in the branches of oak and apple trees, earning reverence from ancient druids who considered it sacred enough to harvest with golden sickles during elaborate ceremonies. The plant’s association with love and fertility led to its incorporation into various magical practices, while its toxic berries provided medieval poisoners with another deadly tool. Mistletoe contains viscotoxins and lectins that can cause severe gastrointestinal distress, low blood pressure, and potentially death, particularly in children who might be attracted to its white berries. However, European folk medicine has long used carefully prepared mistletoe extracts to treat high blood pressure, seizures, and various other conditions. Modern research has focused on mistletoe’s potential as a cancer treatment, with several European countries approving mistletoe extracts as complementary therapy for certain types of cancer. Clinical studies suggest that mistletoe preparations might help improve quality of life and possibly extend survival in some cancer patients, though more research is needed to establish definitive benefits.

Opium Poppy: Paradise and Perdition

The opium poppy produces some of the most beautiful flowers in the garden, their papery petals ranging from pure white to deep crimson, yet the milky latex from their seed pods has shaped human history through both healing and addiction. Ancient Sumerian tablets describe opium as the “plant of joy,” while Greek physicians used it to relieve pain and induce the deep sleep necessary for surgery. Medieval Arab physicians refined opium preparation techniques and documented its effects, passing this knowledge to European healers who incorporated it into various remedies. The plant contains over 80 different alkaloids, including morphine, codeine, and thebaine, which form the basis for many modern pain medications. Today’s pharmaceutical industry still relies heavily on compounds derived from opium poppies, producing everything from prescription painkillers to cough suppressants. However, the same alkaloids that provide blessed relief from severe pain also create powerful addiction, leading to ongoing struggles with opioid abuse that mirror problems societies have faced for thousands of years.

Cannabis: The Ancient Healer’s Controversial Gift

Cannabis has served humanity for over 5,000 years, with ancient Chinese texts describing its use for everything from malaria to absent-mindedness, while Indian traditions incorporated it into religious ceremonies and medical practice. Medieval Islamic physicians documented cannabis preparations for treating epilepsy, inflammation, and pain, even as other cultures viewed its psychoactive properties with suspicion. The plant contains over 100 different cannabinoids, with THC and CBD being the most studied for their distinct effects on the human nervous system. Modern research has revealed that humans possess an endocannabinoid system that naturally responds to compounds found in cannabis, suggesting a long evolutionary relationship between the plant and our species. Current medical applications include treating severe epilepsy, chronic pain, nausea from chemotherapy, and various neurological conditions, though legal restrictions in many areas continue to limit research and access. The plant’s journey from ancient medicine to prohibited substance to emerging pharmaceutical represents one of the most complex relationships between humans and healing plants in modern times.

The herbs that once filled mysterious cauldrons and lined the shelves of wise women continue to reveal their secrets to modern science. These plants bridge the gap between ancient wisdom and contemporary medicine, proving that sometimes the most fantastic stories contain kernels of scientific truth. From belladonna’s role in modern surgery to yew’s transformation into cancer treatment, the witch’s herb cabinet has become humanity’s pharmacy. What other secrets might these green allies still be hiding in their molecular structures?