Somewhere in the North Pacific, a whale calls into the dark with a voice no one expected to hear. Its song peaks around fifty-two hertz, higher than the low thunder of blue whales and lower than the ringing notes of humpbacks. For decades this outlier has slipped past ships and seasons, heard but never confidently seen, a mystery stitched together by microphones and patience. The puzzle is irresistible: Is it one animal, a few, or a lineage hiding in plain sound? And if it is not truly alone, why does its voice sit just off the usual dial?

The Hidden Clues

Scientists first found hints of the odd call in long-term acoustic recordings, where the ocean sounds like an endless, living weather report. Against currents and ship engines, the fifty-two-hertz pattern stood out like a violin note in a tuba section. The structure was consistent across years, the timing seasonal, and the path suggested migration along familiar Pacific corridors. That regularity made it more than a glitch and less than a legend; it looked like biology, not a broken sensor. The call’s persistence forced a simple, unsettling question: who’s singing?

Piecing together the answer meant tracking shapes in sound the way astronomers track light curves, comparing peaks, gaps, and tempo. Researchers mapped call “routes” over vast distances, linking winter and summer grounds the way footprints link a shore to a forest. In those lines, the whale took on a kind of silhouette, not of bone and muscle, but of rhythm. That silhouette proved durable, reappearing year after year like a recurring character in a very long novel. The ocean, it turned out, keeps meticulous audio diaries.

From Navy Ears to Modern Science

The first big break came from arrays built for national security, the undersea microphones once used to listen for submarines. When those networks opened to science, researchers learned that whales had been performing into the system’s tape reels all along. The data were messy but gold-standard: continuous, basin-scale, and stretching across decades. With new algorithms and better calibration, old tapes became time machines for marine biology. It’s a reminder that yesterday’s defense hardware often becomes tomorrow’s discovery tool.

Today, autonomous gliders, cabled observatories, and drifting recorders fill in the gaps the old arrays can’t hear. Machine learning scrubs the static, pulling out signals that would exhaust any human analyst. Cloud databases let teams on different continents compare detections in near real time, turning scattered listening posts into a single acoustic lens. That collaboration shrinks the ocean just enough to follow one odd voice across impossible distances. The lab bench now stretches from Alaska to Baja without leaving the desk.

The Mystery of Fifty-Two

Why the unusual pitch? Blue and fin whales usually sing lower, in tones that tremble just at the edge of human hearing. One popular hypothesis is hybrid heritage – offspring of two species can inherit anatomical quirks that nudge vocal frequency. Another possibility is simply individuality; animals have accents, and some fall far from the herd’s average. The call’s structure shares traits with known species but never matches perfectly, hinting at kinship without handing over a name tag.

There’s also the matter of propagation. Low notes travel astonishingly far in seawater, but background noise and ocean conditions can warp what reaches a recorder. A slightly higher note might cut through certain noise bands the way a bicycle bell slices traffic hum. If the animal learns from its own feedback loop – what carries, what doesn’t – it could be optimizing for reach rather than conformity. In the end, the ocean is both concert hall and mixing board.

Noise, Distance, and the Loneliness Myth

The “lonely whale” label stuck because the call’s frequency looks out of sync with local choirs. But hearing is not the same as matching, and whales perceive a surprisingly wide range of frequencies. An off-key voice can still be obvious and meaningful, especially if it repeats with reliable timing. Social mammals are adaptable; they improvise, overlap, and sometimes tolerate oddities that still carry useful information. The idea of absolute isolation fits our drama, not necessarily their biology.

Ocean noise complicates the picture. Engines, sonar, and storms create a moving patchwork of interference that can mask or reveal different calls from hour to hour. What sounds like solitude in one dataset might be crowded conversation a hundred miles away. I remember listening to a night’s worth of recordings and realizing half the “silence” was just wind chewing up the low end. Once you hear the ocean’s clutter, you stop assuming any singer is truly alone.

Why It Matters

At first glance, an odd whale song seems like trivia – a quirky footnote in a vast field. In practice, it’s a stress test for our assumptions about species boundaries, culture, and communication under pressure. If one whale – or a few – can live slightly off the template and still thrive, it broadens our sense of what counts as normal. That, in turn, affects how we classify populations and prioritize protection. Conservation often hinges on definitions, and definitions often hinge on what we can measure.

Acoustics offer a noninvasive census where nets and tags fall short. Traditional ship surveys miss animals that never surface near the bow; microphones don’t care about fog or light. Long-term sound records show trends in presence, timing, and behavior without ever catching a whale. When those trends shift, they flag changes in food webs, climate, or human impact. One strange voice can be the canary in a cathedral-sized coal mine.

Global Perspectives

The fifty-two-hertz mystery may be North Pacific–centric, but the lesson scales. Around the world, researchers are mapping regional dialects, seasonal song shifts, and cultural traditions passed across generations. Some populations simplify their songs when they rebound in number; others elaborate as social networks expand. It’s a living experiment in how culture and environment coauthor the same melody. Seen that way, the outlier is not an exception but a provocative data point.

These studies tie local stories to global policy. Shipping lanes, seismic exploration, and offshore construction are negotiated at international tables, where evidence must travel well. Acoustic baselines help translate regional anecdotes into widely credible metrics. When nations discuss noise guidelines or sanctuary boundaries, they lean on those baselines. A single unusual whale can sharpen those conversations by reminding everyone what variability looks like in the real ocean.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

Humans have listened to whales for as long as we’ve gone to sea, pressing shells to wooden hulls and guessing at the thunder below. The modern version swaps shells for hydrophones and guesses for statistics, but the instinct is the same: learn by listening. Advances in digital signal processing now pull whole ecosystems out of wav files, like restoring a fresco from a handful of pigments. Patterns that once hid beneath the noise floor rise into clarity as methods improve. Suddenly, a frequency that once seemed like a glitch becomes a signature worth chasing.

What strikes me most is how iterative the work is. Every new instrument makes old data newly valuable, just as a better telescope reinterprets yesterday’s sky. Teams revisit archives and find behaviors no one knew to look for the first time. The fifty-two-hertz story is a case study in that scientific humility. You don’t always need new oceans, just new ways to hear the ones you have.

The Future Landscape

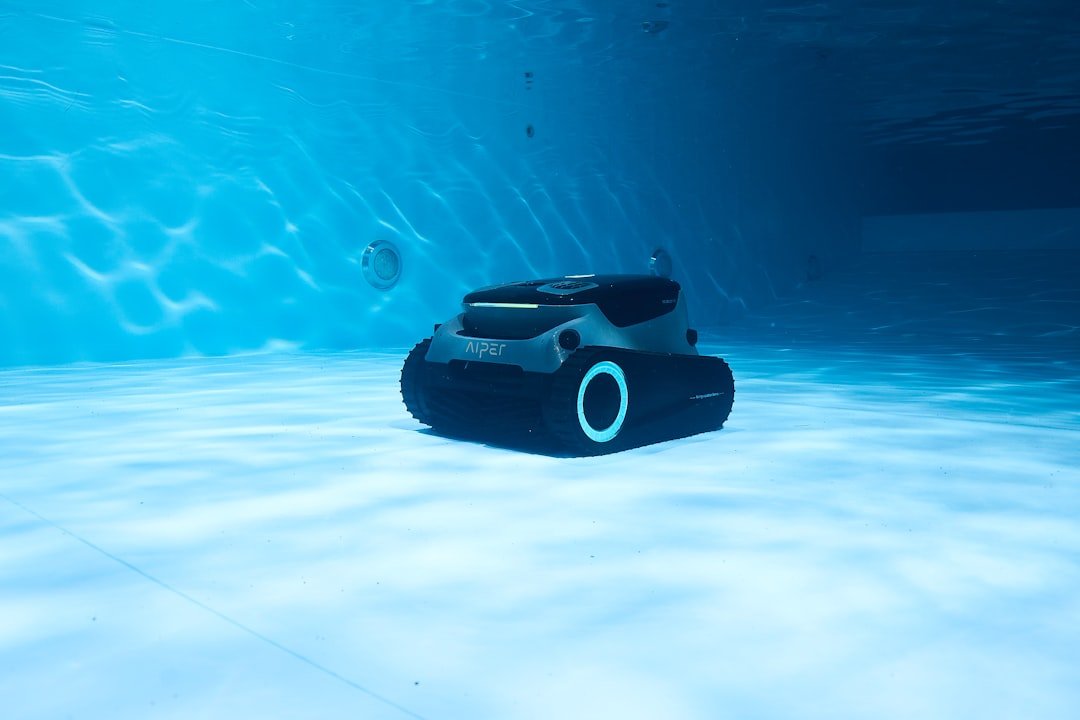

The next leap will likely come from fleets of quiet, long-endurance robots that can follow singers in three dimensions. Pair those with real-time classifiers that flag unusual calls as they happen, and the search becomes proactive rather than archival. Add satellite links and you can pivot ships, drones, or cameras toward a target window while the singer is still on stage. That kind of coordination could finally match a body to the voice without stressing the animal. The goal is finesse, not pursuit.

There are hurdles. Data standards must align so records from different seas and agencies knit cleanly. Privacy concerns around defense-derived archives need careful handling, along with funding that lasts longer than a grant cycle. And the ocean itself is changing; warming, acidification, and shifting prey may rearrange migration maps faster than our plans. Future tools must be adaptable enough to chase a moving mystery without losing the plot.

What You Can Do

Start by paying attention to ocean noise, the background score we often ignore. Support policies that reduce ship speeds near sensitive habitats, because slower props mean quieter seas. When you choose products, consider companies investing in quieter hull designs or routing that avoids key corridors. Small choices can feel symbolic, but symbols add up, especially when they nudge industry norms. Curiosity helps too; the more people who care, the more microphones we can put where they matter.

There are also ways to engage without a passport. Many projects share clips online and invite the public to tag calls, turning spare evenings into real contributions. Classroom programs bring hydrophone data to students, letting the next generation hear science instead of just reading about it. If you’re near the coast, local groups often host listening events that make the sea feel less abstract. Once you’ve heard that odd, steady note, it’s hard to forget it – or to stop wondering who is answering back.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.