You’ve probably heard that reality isn’t quite what it seems at the tiniest scales. Here’s the thing: the quantum world doesn’t just behave strangely. It actually changes when you look at it. Not because your measurement tools are clumsy or imprecise, but because observation itself is woven into the fabric of how reality operates down there. It’s one of those concepts that sounds like science fiction yet has been confirmed in laboratories worldwide. So, let’s dive in and explore why looking at something at the quantum level means you’re not just a passive spectator but an active participant in determining what’s real.

When Particles Refuse to Commit Until You’re Watching

Imagine throwing a coin into the air, except this coin doesn’t land on heads or tails until someone actually checks. When light photons move through space unobserved, they behave as waves, simultaneously passing through both slits and creating interference patterns, but when their path is observed, they behave as discrete particles passing through one slit without creating an interference pattern. This isn’t just theoretical weirdness. Researchers have tested this over and over, and each time the results remain bizarrely consistent.

The implications are staggering. You’re not revealing a pre-existing state when you measure a quantum particle. The act of observation itself influences the behavior of quantum particles, suggesting that the observer plays a crucial role in determining the outcome of the experiment. Think about that for a second: reality at the quantum scale doesn’t exist in a definite state until someone or something interacts with it.

The Famous Double Slit: Reality’s Greatest Plot Twist

In the basic version of this experiment, a coherent light source illuminates a plate pierced by two parallel slits, and the wave nature of light causes the light waves to interfere, producing bright and dark bands that wouldn’t be expected if light consisted of classical particles. Pretty straightforward, right? Waves make wave patterns. Nothing shocking.

Here comes the twist, though. When detectors are placed at the slits, each detected photon passes through one slit as would a classical particle, and particles do not form the interference pattern if one detects which slit they pass through. Just by setting up detectors to see which path the photon takes, you fundamentally alter what happens. The interference vanishes. The photon “chooses” to be a particle instead of a wave, all because you decided to watch. I know it sounds crazy, but this is experimentally verified reality.

Superposition: Being Everywhere and Nowhere at Once

Quantum systems exist in something called superposition. Each state can be expressed as a linear combination of other eigenstates, and given a sufficiently large number of states, every other state can be expressed as a superposition of the original states. Translation: a quantum particle isn’t in one place or another before you measure it. It’s genuinely in multiple states at the same time.

When a measurement of a property is carried out, the wavefunction collapses to one of the state with a defined value for that property, and the measurement corresponding to that particular state is observed. The moment you peek, all those possibilities collapse into one single reality. Before that? The particle legitimately exists in a hazy blur of potential outcomes. This isn’t ignorance on our part; it’s how nature actually works at that scale.

Does Consciousness Cause Collapse? The Controversial Question

Some early quantum physicists toyed with a wild idea: maybe consciousness itself causes the wavefunction to collapse. The postulate that consciousness causes collapse is an interpretation of quantum mechanics that is largely discarded by modern physicists. Most scientists today don’t buy it. The measurement doesn’t require a conscious mind; any interaction that leaves a record will do the job.

The need for the observer to be conscious is not supported by scientific research and has been pointed out as a misconception rooted in a poor understanding of the quantum wave function and the quantum measurement process. Still, the question haunts the edges of quantum theory: what exactly counts as an “observation”? Is it when a photon hits a detector? When information becomes irreversible? We don’t have perfect answers yet, which keeps philosophers and physicists arguing late into the night.

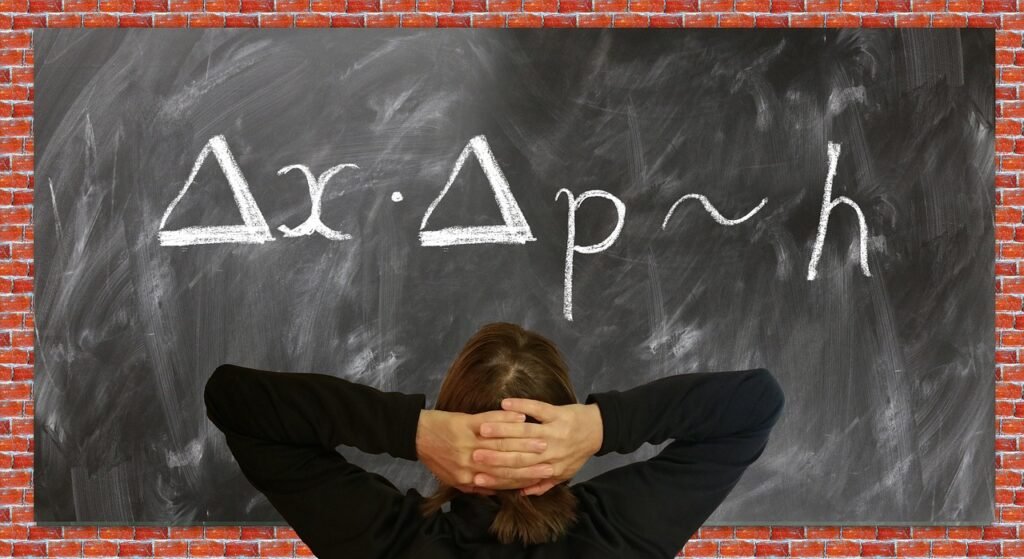

Heisenberg’s Uncertainty: The Universe Has Built-in Limits

The uncertainty principle states that there is a limit to the precision with which certain pairs of physical properties can be simultaneously known; the more accurately one property is measured, the less accurately the other property can be known. Position and momentum. Energy and time. These pairs are locked in a cosmic trade-off.

This isn’t about crude measuring tools disturbing tiny particles. In quantum mechanics, a particle cannot have both a definite position and momentum; the limitations described by Heisenberg are a natural occurrence and have nothing to do with any limitations of the observational system. Reality itself is fundamentally uncertain at the quantum level. You can’t know everything about a particle because there isn’t everything to know until you choose what to measure.

Wave Function Collapse: From Possibility to Actuality

Wave function collapse occurs when a wave function initially in a superposition of several eigenstates reduces to a single eigenstate due to interaction with the external world, and this interaction is called an observation and is the essence of a measurement in quantum mechanics. It’s the moment quantum possibilities snap into classical reality.

Wave function collapse implies that reality doesn’t decide on an outcome until an observation is made; this isn’t just ignorance, it’s a fundamental indeterminacy. Think about how profoundly strange this is. The universe doesn’t have a definite answer about where an electron is until something forces it to commit. Observation creates the concrete world from a fog of potentials.

Quantum Entanglement: Spooky Action Across the Universe

Einstein hated this one. Einstein disparaged quantum mechanics for seemingly exhibiting “spukhafte Fernwirkung” or “spooky action at a distance,” meaning the acquisition of a value of a property at one location resulting from a measurement at a distant location. When two particles become entangled, measuring one instantly affects the other, no matter how far apart they are.

Any measurement of a particle’s properties results in an apparent wave function collapse of that particle, and with entangled particles, such measurements affect the entangled system as a whole. Measure the spin of one particle, and its entangled partner immediately “knows” what state it should be in. Not because information travels between them faster than light, but because they’re part of a single quantum system. Honestly, it’s one of the most counterintuitive aspects of quantum mechanics, yet experiments confirm it again and again.

The Measurement Problem: What Counts as Looking?

Here’s where things get philosophically messy. The Schrödinger equation describes quantum systems but does not describe their measurement; solution to the equations include all possible observable values, but measurements only result in one definite outcome, and this difference is called the measurement problem of quantum mechanics. We have equations that predict probabilities beautifully, but they don’t tell us when or how the collapse actually happens.

Some branches of probability, called QBism, argue that an observer’s personal beliefs about a quantum system could result in the observation of distinct outcomes or realities. Different interpretations offer wildly different answers. Is collapse a real physical process? Is it just about information becoming available? Do parallel universes branch off with every measurement? Decades after quantum mechanics was formulated, we still debate these fundamental questions.

Why This Matters Beyond the Laboratory

You might wonder why any of this matters in your daily life. Fair question. The quantum world seems impossibly removed from the solid, predictable reality we experience. Yet quantum mechanics underlies everything from the electronics in your phone to the chemical bonds that make up your body. MIT physicists performed an idealized version of the double-slit experiment, confirming that light exists as both a wave and a particle but cannot be observed in both forms at the same time. These aren’t just abstract puzzles; they’re descriptions of how reality actually works.

The use of quantum entanglement in communication and computation is an active area of research and development. Quantum computers, quantum cryptography, and other technologies are being built on these strange principles. Understanding that observation fundamentally changes quantum systems isn’t just philosophical navel-gazing. It’s the foundation for the next generation of technology that will reshape our world.

The Philosophical Earthquake That Never Stops Shaking

The observer effect is the disturbance of an observed system by the act of observation, often the result of utilizing instruments that alter the state of what they measure. At macroscopic scales, this effect is negligible. But at quantum scales, it becomes the defining feature of reality itself.

What does it mean that reality doesn’t have definite properties until measured? Are we creating reality through observation, or just revealing what was always there in potential form? These questions push at the boundaries of science and philosophy. The very act of observation not only reveals but also produces the properties of quantum objects, a concept that has profound implications for our understanding of reality at the most fundamental level. Whether you find that thrilling or unsettling probably depends on your temperament, but either way, it’s how our universe operates down at its smallest scales.

Looking at the quantum world changes it. That’s not a bug in our theories or a limitation of our equipment. It’s a feature of reality itself. The boundary between observer and observed dissolves at the quantum level, and we’re left with a universe far stranger and more interconnected than classical physics ever imagined. What do you think about observation creating reality? Does it challenge your understanding of what’s real?