Somewhere above you right now, bathing the entire sky in a faint glow, is the oldest light in the universe. It’s not a distant galaxy or a dramatic supernova, but a ghostly afterglow from when the cosmos was a chaotic, blisteringly hot fog. This ancient radiation, called the cosmic microwave background, is like a baby picture of the universe taken long before stars, planets, or anything familiar existed.

For decades, scientists have treated this light as a gold mine of information, using it to measure the age of the universe, its composition, and even how fast it’s expanding. And yet, the deeper we look into this faint glow, the more uncomfortable questions it raises. The universe’s oldest light has told us a lot – but it has also exposed cracks in what we thought we knew.

The Moment The Cosmos Became Transparent

Imagine the early universe as a dense, brilliant fog where light could not travel freely, constantly bouncing off particles like headlights in a blizzard. For the first several hundred thousand years, the cosmos was so hot and energetic that atoms couldn’t even form properly, and photons – particles of light – were relentlessly scattered. Then, as the universe expanded and cooled, protons and electrons finally joined to form neutral atoms, and something dramatic happened: the fog cleared.

That clearing, often called recombination, is when the cosmic microwave background (CMB) was released, roughly about three hundred and eighty thousand years after the Big Bang. From that moment on, light could travel nearly unimpeded across space, carrying with it an image of the universe as it looked at that time. When we detect the CMB today, we’re effectively seeing that ancient snapshot stretched and cooled by billions of years of expansion, shifted into the microwave part of the spectrum. It’s like finding an old, faded photograph in an attic, except the attic is the entire sky.

A Baby Picture That Mapped The Entire Universe

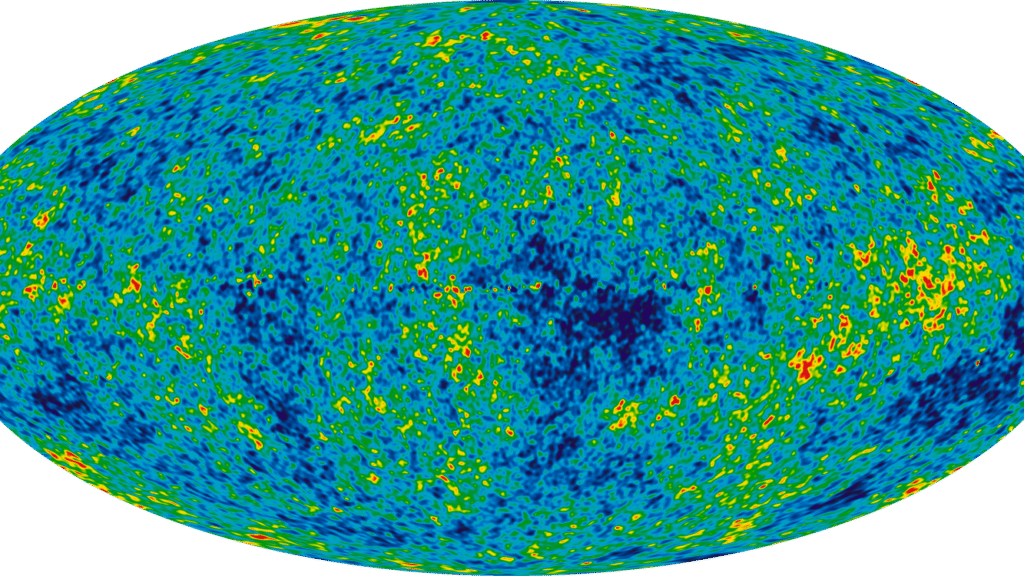

When satellites like COBE, WMAP, and Planck mapped the CMB in ever finer detail, the results were quietly astonishing. The sky was not uniform; it was sprinkled with tiny temperature variations, differences of less than a thousandth of a degree. Those small fluctuations are not random noise, but the seeds of everything – the places where gravity would later pull matter together to form galaxies, clusters, and eventually stars and planets.

By analyzing the pattern of these fluctuations, scientists could read off fundamental properties of the universe with surprising precision. The CMB has revealed that ordinary matter makes up only a small fraction of everything that exists, while dark matter and dark energy dominate the cosmic budget. It has pinned down the overall age of the universe to nearly fourteen billion years and confirmed that space on large scales is extremely close to flat. It’s hard to overstate how wild it is that a faint microwave glow can function like a cosmic instruction manual.

The Almost-Perfect Glow That Shouldn’t Be This Perfect

One of the first shocking discoveries about the CMB was how incredibly uniform it is. Nearly every patch of sky has practically the same temperature, with only those tiny fluctuations layered on top. The problem is that, according to simple versions of Big Bang theory, distant regions of the universe were never in contact with each other early on. They should never have had time to “agree” on a common temperature.

This puzzle is known as the horizon problem, and it led to the idea of cosmic inflation: a brief, mind-bendingly rapid expansion very early in the universe’s history. Inflation, if it happened, could stretch any initial irregularities flat and give distant regions a shared past before they were yanked apart faster than light could catch up. The CMB’s near-uniformity is one of the main reasons inflation became the leading explanation, but the catch is that nobody has directly seen inflation itself. So the CMB is both the best evidence we have for this wild idea and a reminder that a key piece of the story is still missing.

For all its overall smoothness, the CMB also contains some unsettling oddities that still bother cosmologists. When the sky is broken down into large-scale patterns, some measurements suggest that the fluctuations are not perfectly random in every direction. Instead, there appear to be strange alignments and asymmetries, particularly on the largest angular scales. One of these patterns has been dramatically nicknamed the “axis of evil,” because it seems to mark a preferred direction in the sky where the CMB fluctuations line up more than expected.

If these features are real and not just statistical flukes or leftover noise from our instruments or the Milky Way, they could hint that our basic cosmological model is incomplete. A preferred direction in the universe would clash with the long-held idea that, on large scales, the cosmos has no special places or directions. Some researchers suspect these anomalies are telling us something deep, while others think we’re over-interpreting messy data. The uncomfortable truth is that, even now, the universe’s oldest light might be shrugging and saying, “Look closer, you’re not done yet.”

The Hubble Tension: When Old Light And New Light Disagree

In recent years, one of the biggest dramas in cosmology has come from a number that should be simple: how fast the universe is expanding today. The CMB lets scientists infer this expansion rate indirectly by fitting a model to the early-universe data and extrapolating forward. Meanwhile, observations of nearby galaxies and exploding stars measure the expansion directly in the local universe. The uncomfortable twist is that these two approaches do not agree; the local measurements give a higher expansion rate than the CMB-based prediction.

This mismatch, often called the Hubble tension, has stubbornly refused to go away, even as measurements on both sides have become more precise. If the CMB says one thing and the nearby universe says another, then either we are missing some new physics, or we are underestimating subtle errors in how we interpret one or both sets of data. Ideas on the table range from new kinds of dark energy to tweaks in the early-universe behavior of particles. The CMB, instead of settling the matter, has become a key witness in a growing cosmic disagreement.

The Hunt For Primordial Gravitational Waves

There’s a more subtle secret buried in the CMB that scientists are still digging for: a pattern of polarization that would be the fingerprint of primordial gravitational waves. These waves would be ripples in space-time generated during inflation, leaving behind a faint twisting pattern in the orientation of CMB light. Detecting this pattern would be like finding a fossil from the first instant after the Big Bang, a direct clue to physics at energies we can’t touch in any lab.

Several observatories have chased this signal, from ground-based telescopes in Antarctica and the Atacama Desert to balloon experiments floating above the atmosphere. One high-profile claim of detection turned out to be dust in our own galaxy masquerading as the signal everyone wanted to see. That false alarm was a painful reminder of how tricky these measurements are. Still, new experiments continue to push the limits, because if the universe’s oldest light is whispering about gravitational waves from the dawn of time, that’s a whisper worth straining to hear.

Dark Matter, Dark Energy, And What The CMB Doesn’t Show

In a strange way, the CMB has helped prove the existence of things we still don’t really understand at all. The pattern of fluctuations only makes sense if there is a lot of invisible matter that doesn’t interact with light, the so-called dark matter, shaping the growth of structure. On top of that, to explain the way the universe’s expansion is speeding up, dark energy has to be part of the picture as well. The CMB nails down how much of each ingredient there seems to be, but it’s eerily silent about what they truly are.

This leaves us in an odd position: the universe’s oldest light has mapped the outlines of the cosmic story but left the main characters in shadow. Dark matter might be some new particle, or many particles, or even something stranger like a change in gravity on large scales. Dark energy could be an energy of empty space itself or a sign that our equations are missing a crucial term. The CMB keeps pointing to their presence, like footprints in fresh snow, but it refuses to tell us who left them.

New Eyes On The Oldest Light

Even though the CMB was discovered back in the mid-twentieth century, we’re still building new instruments to look at it in sharper and more creative ways. Current and planned projects across the globe aim to measure its temperature and polarization with breathtaking precision, detecting ever-fainter signals and smaller patterns. Each new generation of telescopes brings the hope of either confirming the standard cosmological model more solidly or poking holes in it in ways we can’t ignore.

At the same time, new observatories that study other wavelengths and cosmic messengers, like neutrinos and gravitational waves, are starting to overlap with what the CMB tells us. By comparing all of these different cosmic probes, scientists can check whether they all tell the same story or hint at inconsistencies that reveal new physics. It’s ironic but fitting: the universe’s oldest light stays the same, but our ways of listening to it keep evolving. The real secret might not be in getting one perfect picture, but in seeing how many different ways that ancient glow can still surprise us.

A Silent Glow With A Loud Message

The cosmic microwave background began as a blinding, chaotic fog and has ended up as a faint, uniform glow quietly filling the sky. From that glow we’ve learned the age, shape, and ingredients of the universe, and we’ve tested ideas about the Big Bang, inflation, and the growth of cosmic structure. At the same time, this ancient light has exposed mysteries that refuse to be swept aside, from troubling anomalies and cosmic tensions to the nature of dark matter, dark energy, and the very first moments of existence.

We like to think of the CMB as a finished snapshot in some cosmic photo album, but it’s more like a puzzle that keeps revealing new missing pieces the closer we look. The universe’s oldest light is steady, patient, and unforgiving; it does not bend to what we want to be true. It simply shines, carrying a record of what really happened. In the end, the question it leaves hanging over us is quietly unnerving: how much of the story written in that light have we actually learned, and how much is still hiding between the pixels?