For more than a century, astronomers have been measuring how quickly the universe is flying apart, quietly assuming that with better telescopes and cleaner data, all the numbers would eventually agree. Instead, the opposite is happening. New observations, from ultra-precise space telescopes to clever uses of exploding stars and gravitational waves, are sharpening a puzzle that will not go away: the universe appears to be expanding faster than our best theories predict. This mismatch is not a tiny rounding error; it is large enough that many cosmologists now suspect something fundamental is missing from our picture of reality. At stake is not just a single number, but our understanding of dark energy, dark matter, and even whether Einstein’s theory of gravity is the whole story.

The Hidden Clues in Cosmic Starlight

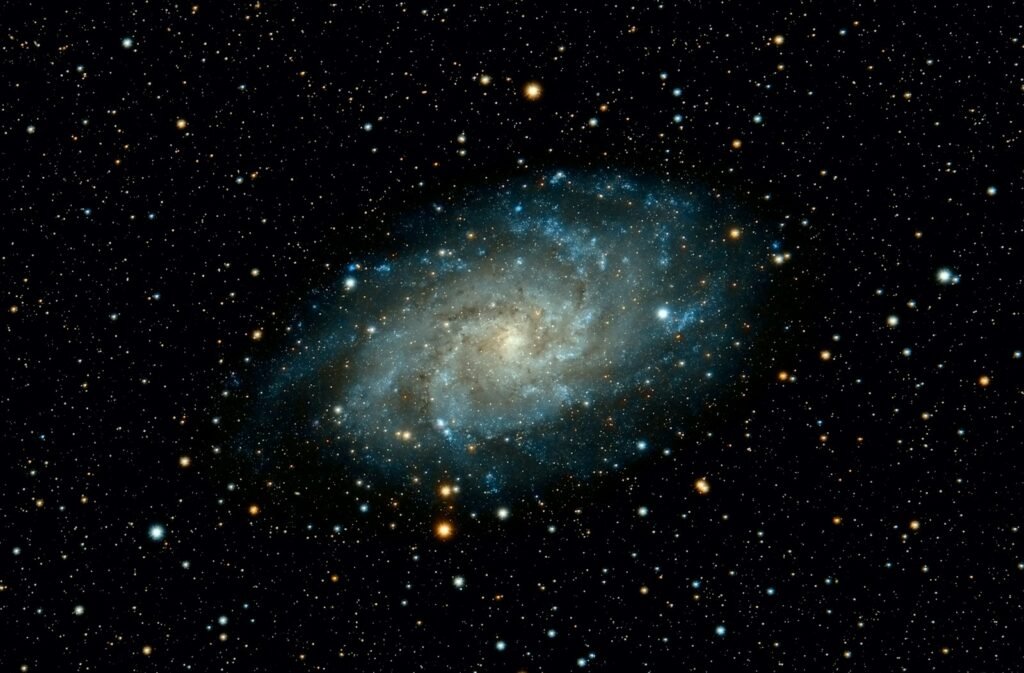

It might sound abstract, but this entire drama comes down to a deceptively simple question: how quickly are galaxies moving away from each other right now? Astronomers express that rate with a single number called the Hubble constant, and they hunt for it in faint, distant starlight. Using the Hubble Space Telescope and, more recently, the James Webb Space Telescope, teams have been measuring the distances to special “standard candle” stars whose true brightness is well understood, then watching how stretched their light becomes as space itself expands. The more the light is stretched, the faster that patch of the universe is receding from us. When you pile up thousands of these measurements, a picture emerges, and in recent years that picture has stubbornly pointed to a faster-than-expected expansion.

Here’s the twist: when scientists use the afterglow of the Big Bang, the cosmic microwave background, to infer the same expansion rate, they get a slower value. The first method looks at the nearby universe as it is today; the second rewinds the clock to just after the Big Bang and uses our best cosmological model to “fast-forward” to the present. Those two approaches should land on the same number, but they do not, and the gap is too big to comfortably blame on measurement sloppiness. To many researchers, this suggests that the hidden clues in cosmic starlight are not just technical quirks; they are fingerprints of new physics written across the sky.

From Hubble’s First Glimpse to Today’s Cosmic Tension

When Edwin Hubble first announced in the late 1920s that distant galaxies were racing away from us, it overturned the long-standing idea of a static universe. His early measurements were rough, off by a factor of several compared with modern values, but the basic insight was revolutionary: space itself was stretching. Over the decades, refinements in distance measurements using variable stars and supernovae pulled the Hubble constant into a narrower and narrower range. For a while, the field was split into two camps, one favoring a slower expansion and one a faster one, but most people expected new data to force a tidy convergence.

Instead, by the mid‑2010s, a new kind of disagreement had emerged, now nicknamed the “Hubble tension.” Local measurements, based on stars and supernovae in the nearby universe, consistently landed on a higher value than estimates derived from the cosmic microwave background. Crucially, the uncertainties on both sides shrank while the discrepancy remained, turning what could have been a passing annoyance into a genuine scientific problem. In 2025, the situation is even sharper, thanks to exquisitely calibrated distance ladders and more sophisticated analyses of the early universe. The old story of messy data gradually settling down has been replaced by a stranger one: the better we measure, the louder the tension becomes.

New Data, New Tools: Webb, Supernovae, and Standard Sirens

The claim that the universe is expanding faster than we thought lives or dies on the quality of the data, and that data has never been better. The James Webb Space Telescope has given astronomers an unprecedented look at Cepheid variable stars, one of the rungs in the cosmic distance ladder, in galaxies where supernovae have also exploded. By resolving these stars more cleanly and reducing contamination from surrounding light, Webb has helped confirm that earlier Hubble measurements were not simply misled by blurry images or crowding. That alone has made the faster-expansion camp harder to dismiss as a calibration fluke.

Meanwhile, other teams are cross-checking the story using totally different cosmic yardsticks. Exploding white dwarf stars, known as Type Ia supernovae, have long been used as standard candles, but recent surveys have expanded the sample to thousands of events stretching deep into cosmic history. Even more exciting, astronomers are starting to use gravitational-wave events – collisions of neutron stars and black holes – as “standard sirens,” where the ripples in spacetime itself encode distance information. Each method comes with its own assumptions and sources of error, yet many of them are converging on the same unsettling conclusion: today’s universe seems to be racing apart more quickly than the standard model of cosmology predicts.

Peeking Behind the Numbers: What Might Be Going On?

When a single experiment behaves oddly, you look for a loose cable; when many independent experiments misbehave in the same direction, you start wondering whether the theory is wrong. That is roughly where cosmology stands with the Hubble tension. One possibility is that dark energy – the mysterious component thought to drive the accelerated expansion of the universe – is not a simple, unchanging property of space. If its strength has evolved over time, or if there are additional fields or particles lurking in the dark sector, that could alter the inferred expansion rate in subtle ways. Another possibility is that we have not fully accounted for how matter clumps and flows on very large scales, which might bias some local measurements.

There is also the nuclear physics angle: the cosmic microwave background analysis depends on how light elements formed in the early universe, which in turn depends on rates of subatomic reactions measured in laboratories today. Small tweaks to those rates could ripple into revised cosmological parameters. More radically, some researchers have floated the idea that Einstein’s general relativity, while astonishingly successful in many tests, might need modification on the largest scales. None of these ideas has yet delivered a clean, widely accepted solution, but they highlight how a single stubborn number is forcing us to stress-test our deepest assumptions about space, time, and matter.

Why It Matters: Rethinking the Blueprint of the Cosmos

It can be tempting to treat the Hubble constant as just one more technical detail for specialists to argue about, like bickering over the exact nutritional label on a cosmic cereal box. In reality, that single number is woven into almost every statement we make about the universe: its age, its size, and the relative amounts of dark matter and dark energy. If the expansion is faster than expected, then the universe could be a bit younger than we thought, or its contents could be apportioned differently than current models suggest. That has knock-on effects for when the first stars and galaxies formed, how structures grew, and how long the current era of accelerated expansion might last.

Beyond the raw numbers, there is a deeper reason this matters: it is a stress test of the idea that we already have a nearly complete blueprint of the cosmos. Over the past few decades, the so-called standard model of cosmology has seemed almost too successful, explaining a huge range of observations with a relatively small set of parameters. The Hubble tension is a reminder that even a well-fitting theory can hide cracks that only become visible with sharper tools. In a way, this is science working exactly as it should: when precise observations collide with cherished models, we do not smooth over the difference; we follow it, even if it leads to uncomfortable questions about what we still do not know.

Human Stories Behind the Cosmic Numbers

Behind every crisp plot of data points and every decimal place in the Hubble constant, there are real people puzzling over late-night coffee and arguing across whiteboards. I still remember covering my first big cosmology conference, sitting in the back of a packed room as one team unveiled new measurements that made the tension worse, not better. You could feel the mix of excitement and unease ripple through the audience, an odd combination of “this is thrilling” and “this could blow up my thesis.” That emotional whiplash has only intensified as young researchers build entire careers around trying to crack this problem while senior scientists re-examine assumptions they once considered settled.

In conversations, some admit a quiet hope that the tension survives every attempt to explain it away, because that would virtually guarantee new physics. Others are more cautious, haunted by past anomalies that evaporated when better data arrived. What strikes me is how collaborative and adversarial the process is at the same time: groups double-check each other’s calibrations, reanalyze shared data sets, and openly publish methods so critics can poke holes. It is a reminder that science is not a sterile march toward truth but a very human, sometimes messy negotiation with nature, where the universe always has veto power.

The Future Landscape: Telescopes, Surveys, and New Cosmic Rulers

The next decade is poised to be brutal – in a good way – for the Hubble tension, because new observatories will either resolve it or make it impossible to ignore. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, with its vast sky survey, will capture millions of supernovae and map how structures grow over time, offering multiple independent routes to the expansion rate. The Euclid mission and NASA’s upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope are designed to probe dark energy by measuring the shapes and distances of galaxies across enormous volumes of space. Together, these projects will produce a deluge of data that could reveal whether the faster expansion is baked into the fabric of the cosmos or an artifact of how we are reading the sky.

Gravitational-wave astronomy is another wild card. As detectors become more sensitive and more neutron-star mergers are recorded, standard sirens could provide a clean, physics-based measure of cosmic distances that bypasses some of the messiness of traditional candles. If those sirens agree with the faster local measurements, the case for new physics would strengthen dramatically; if they side with the slower early-universe value, theorists will have a different kind of puzzle. Either way, by the early 2030s, it is hard to imagine the Hubble constant remaining a fuzzy question mark. The universe may not hand us a simple answer, but it will not stay coy forever.

How You Can Stay Engaged with a Moving Universe

For most of us, the expansion rate of the universe does not affect what we make for dinner or whether we hit traffic tomorrow morning, but it does shape the bigger story we tell ourselves about where we came from and where we are headed. One simple way to stay engaged is to follow missions like Hubble, Webb, Euclid, Rubin, and Roman through their public image releases and science updates; many observatories now share behind-the-scenes looks at how discoveries are made. Supporting science journalism, public lectures, and planetariums helps create the ecosystem that turns raw data into understandable narratives. If you are inclined toward numbers, there are even citizen-science projects that let you help classify galaxies or spot supernovae in survey images.

On a more personal level, I find that paying attention to stories like the Hubble tension is a kind of antidote to cynicism. It is hard to stay entirely jaded when you watch thousands of people around the world argue passionately – but rigorously – about a single number because it might reveal something profound about reality. Sharing those stories with friends, kids, or students keeps the sense of cosmic curiosity alive, even if none of us will ever touch a space telescope mirror. The universe is literally slipping through our fingers as it expands, but our understanding of it is expanding too, and that is something almost anyone can be part of just by staying curious.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.