Walk outside on a clear night, look up, and you’re staring at a contradiction that keeps some of the world’s best physicists awake at 3 a.m. For more than a century, cosmologists have believed they understood how fast the universe is growing, only to find in the past decade that their answers simply do not agree. Two independent ways of measuring the expansion of the cosmos now clash so sharply that many researchers say something in our picture of reality has to give. This is not a minor numerical quibble over decimal places; it is a deep, nagging inconsistency that cuts into the foundations of modern physics. The story of why the universe is expanding faster than it “should” is not finished yet, but it is already one of the most gripping scientific mysteries of our time.

From Einstein’s Blunder To A Measured Expanding Cosmos

When Albert Einstein first wrote down his equations of general relativity in the 1910s, they implied a dynamic universe that should expand or contract, but he was convinced the cosmos had to be static. To keep everything frozen in place, he added a term called the cosmological constant, a kind of mathematical anti-gravity that balanced things out, and later reportedly regretted it when evidence for expansion emerged. In the late 1920s, observations by Edwin Hubble and others showed that distant galaxies’ light is stretched, or redshifted, in a way that points to space itself expanding. That discovery turned the cosmological constant from a patch into a discarded relic, and the expansion rate became encoded in what we now call the Hubble constant, a single number describing how fast galaxies recede with distance.

Throughout the twentieth century, measuring that number became a sort of holy grail of observational cosmology, and for decades the estimates varied wildly. As telescopes improved and distance-measuring techniques matured, astronomers converged on a value that seemed broadly consistent with other observations of the universe’s size and age. By the late 1990s, the shock was no longer that the universe was expanding, but that the expansion itself was accelerating, pushed faster and faster by some mysterious “dark energy.” What looked, for a while, like a tidy story of an expanding universe with a well-behaved growth rate has since unraveled into a more tangled and uncomfortable puzzle.

The Hubble Constant: One Number, Two Incompatible Answers

The core of today’s problem is deceptively simple: two high-precision methods for determining the Hubble constant give answers that are stubbornly, statistically, and increasingly incompatible. One method looks at the early universe, using the cosmic microwave background radiation – faint leftover light from about 380,000 years after the Big Bang – to infer what the expansion rate should be today. The other method measures the present-day universe directly, building a “distance ladder” from nearby stars to faraway galaxies to see how fast space is expanding right now. If our cosmological model is correct, those two answers ought to line up within their margins of error, the way two independent measurements of a bridge’s length should agree.

Instead, the value derived from early-universe data consistently comes out lower than the value measured from the local universe, and the gap is not shrinking as the data get better. The early approach, relying heavily on measurements from satellites like Planck, points to a Hubble constant that suggests a slightly slower expansion rate. The local approach, driven largely by observations of pulsating stars called Cepheids and stellar explosions known as Type Ia supernovae, points to a faster expansion today than the early-universe prediction allows. With each new dataset and careful cross-check, the tension between them has grown from a curiosity into what many now frankly call a crisis.

How We Read The Baby Picture Of The Universe

The most distant “photograph” we have of the cosmos is the cosmic microwave background, a nearly uniform glow of microwave radiation that fills the sky. Tiny temperature variations in this glow, mapped in exquisite detail by missions like WMAP and Planck, encode information about the composition, geometry, and early evolution of the universe. By fitting these patterns with the standard cosmological model – often called Lambda-CDM, for dark energy plus cold dark matter – scientists can infer the universe’s age, the relative amounts of matter and dark energy, and the expansion rate implied by that model. This is not a direct clock reading, but more like reconstructing the rules of a game from a single snapshot of play.

In that reconstruction, the cosmic microwave background tells a remarkably consistent story when combined with other large-scale probes like galaxy clustering and gravitational lensing surveys. The model that fits the data so well predicts a universe that is about 13.8 billion years old and yields a specific Hubble constant that falls on the “slower” side of today’s measurements. For a while, this early-universe route was widely seen as the gold standard because the physics of the hot, young cosmos is relatively simple and well tested in other areas of physics. That makes the current disagreement all the more jarring: if the early picture is right, the late-time universe seems to be misbehaving.

The Distance Ladder And A Faster Local Universe

On the other side of the cosmic argument is the distance ladder, which depends on carefully calibrated steps from our galactic neighborhood out to hundreds of millions of light-years away. Astronomers start by using geometric methods, like parallax, to measure distances to nearby stars directly as Earth orbits the Sun. Some of these stars are Cepheids, whose regular brightness variations reveal their true luminosity, letting researchers use them as reliable “standard candles” in more distant galaxies. In those same galaxies, they then observe Type Ia supernovae, stellar explosions that reach similar peak brightness and can be seen across vast gulfs of space.

By chaining these steps together, teams like SH0ES have built an independent route to the Hubble constant that barely touches the cosmic microwave background data at all. Their result repeatedly comes out higher than the early-universe estimate, implying that galaxies are receding faster per unit distance than the standard model expects. This method has gone through painful rounds of error-checking: recalibrated distances, different instruments, alternative standard candles like red giant branch stars, and extensive cross-comparisons. Yet the basic conclusion survives these tests, undermining the idea that one side simply mis-measured the cosmic yardstick and forcing cosmologists to consider more radical explanations.

Systematic Errors Or Something New In Physics?

The first instinct of most scientists faced with such a clash is to suspect systematic errors – hidden biases or overlooked effects in the measurements or analysis. Maybe dust in distant galaxies subtly alters the brightness of supernovae, or perhaps modelling assumptions in the cosmic microwave background analysis are too rigid. Over the past several years, though, a wave of independent teams has deliberately set out to poke holes in both sets of methods, often with competing analyses using different data. So far, the uncomfortable truth is that while every measurement has uncertainties, no obvious single mistake explains away the entire tension.

As a result, the conversation has shifted toward the possibility that the standard cosmological model itself may be missing a crucial ingredient. Proposals include an early episode of extra dark energy that briefly altered the expansion rate, additional species of ultra-light particles, or subtle changes in how gravity behaves on the largest scales. None of these ideas has yet emerged as the clear front-runner, in part because they often solve the Hubble problem at the cost of creating other mismatches with existing data. Cosmologists now find themselves in a delicate position: pushing for bold new physics while being ruthlessly careful not to over-interpret the current clues.

Why This Tension Cuts To The Core Of Cosmology

At first glance, arguing over a number that describes how fast galaxies recede might sound technical, even esoteric, but the stakes are surprisingly deep. The Hubble constant sits at the heart of our cosmic timeline, shaping our estimates of the universe’s age, the size of observable space, and the way structures like galaxies and clusters grew over billions of years. If the expansion rate is off, so is our reconstruction of when key cosmic milestones occurred, from the first stars igniting to the assembly of the Milky Way itself. In that sense, the Hubble tension is not just a disagreement about motion; it is a challenge to the narrative we have built about how the cosmos came to look the way it does today.

On a more philosophical level, the clash exposes the limits of our proudest theories at a time when they seemed most secure. The combination of general relativity and the standard cosmological model was, until recently, held up as a triumph comparable to the periodic table or the genetic code, a sign that we had grasped the broad strokes of the universe. Now, the Hubble tension hints that a seemingly small discrepancy might be the loose thread that, when pulled, reveals a deeper pattern. As someone who has covered physics for years, I’m struck by how many seasoned researchers compare this moment, cautiously, to the years before quantum mechanics emerged, when little anomalies hinted that classical physics was not the final word.

New Windows On Expansion: Lenses, Waves, And Standard Sirens

To break the stalemate between early and late measurements, astronomers are turning to new kinds of cosmic tools that bypass some of the old assumptions. One promising approach uses strong gravitational lensing, in which the gravity of a massive galaxy bends the light from a more distant quasar or supernova into multiple images. By carefully measuring the time delays between brightness variations in those images, researchers can infer distances and thus estimate the Hubble constant in a way that does not rely on Cepheids or the cosmic microwave background. Another increasingly powerful method uses gravitational waves from colliding neutron stars as “standard sirens,” since the waveform directly encodes how far away the event occurred.

Each of these emerging techniques comes with its own challenges, from the need for large samples to the complexity of modeling intervening matter, but together they offer much-needed independent checks. So far, their results tend to land somewhere between the early-universe and local-universe values, with uncertainties still large enough to avoid taking sides outright. As future surveys from observatories like the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, Euclid, and the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope ramp up, the volume and precision of data will increase dramatically. The hope among many is that within the next decade, these multiple lines of evidence will either converge on a single value or force a decisive break with the current cosmological model.

Living With A Universe That Refuses To Behave

For now, we are stuck with a universe whose expansion rate appears to depend on how we choose to measure it, which is a deeply unsettling place for a supposedly mature field to be. Some scientists have grown more comfortable talking openly about this discomfort, because acknowledging the mess is often the first step toward real progress. Others emphasize patience, remembering how often apparent crises in physics have evaporated once better data or new analysis techniques arrived. Personally, I find it oddly reassuring that, even after decades of exquisite measurements and powerful theories, the cosmos still has the capacity to surprise us in ways that feel almost mischievous.

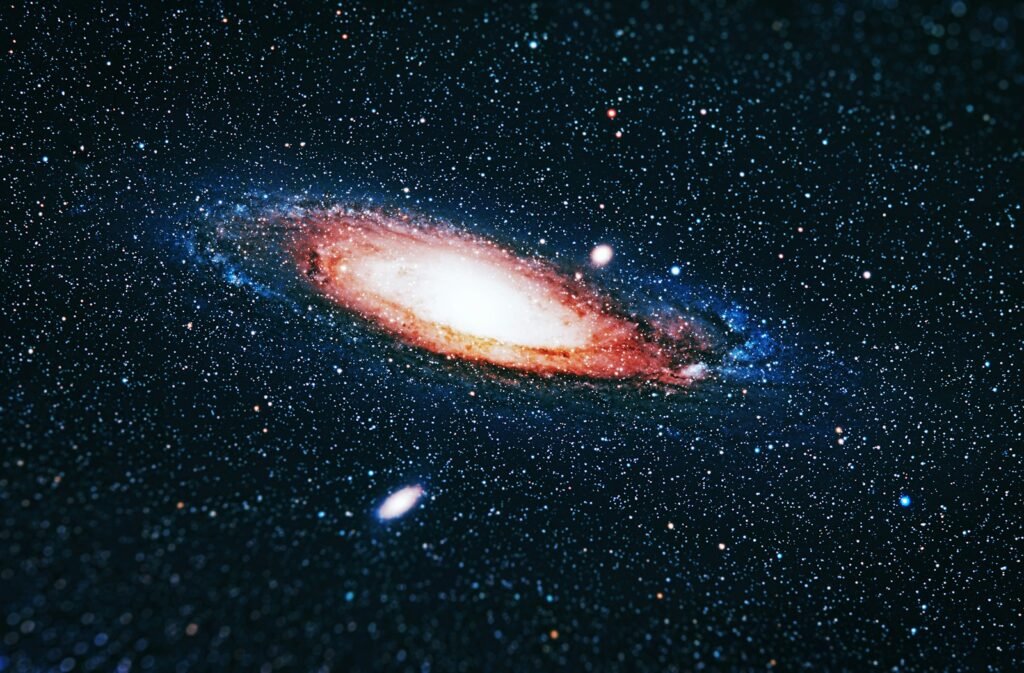

If you’re reading this from your laptop or phone, there are quiet, practical ways to engage with this unfolding story beyond just scrolling past the headlines. You can follow public releases from major observatories, look up open-source visualizations of the cosmic microwave background, or even join citizen science projects that help classify galaxies and gravitational lenses. The next time you see a crisp image of a distant galaxy cluster, you might remember that buried in its arcs and distortions is another clue to how fast the universe is stretching. And when you step outside at night, it is worth pausing for a moment on the strange fact that space itself is racing outward faster than we can currently explain, leaving us with a question that is as simple to state as it is hard to answer: why?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.