They look like something out of a fever dream: two funnels chewing across the same skyline, carving parallel scars into fields and memory. For decades, double tornadoes were treated like meteorological folklore, the kind of thing you heard about from a neighbor’s cousin. Now, high-resolution radar and storm-chaser videos have turned the mystery into a solvable puzzle, though it’s still a puzzle with missing pieces. The core question remains unsettling and fascinating: why do some storms spin out a second monster while the first is still alive? The answer, scientists say, hides in the fine print of wind, temperature, and chaos.

The Hidden Clues

Double tornadoes often begin as a storm that can’t decide where to put its energy, a supercell splitting or cycling while holding onto more than one zone of spin. I remember watching a slow-motion clip of a Plains storm where the broader cloud base looked like a restless sea, eddies forming and collapsing in seconds. Those eddies, called mesocyclones, are the storm’s internal gears, and sometimes a second gear kicks in before the first one grinds to a halt. When that overlap happens near the ground, two separate funnels can emerge and briefly coexist. From the road, it looks like a shocking magic trick; on radar, it’s a balancing act between competing swirls. The clues are there, but they flash by fast, which is why the best evidence still comes from rare, lucky angles.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

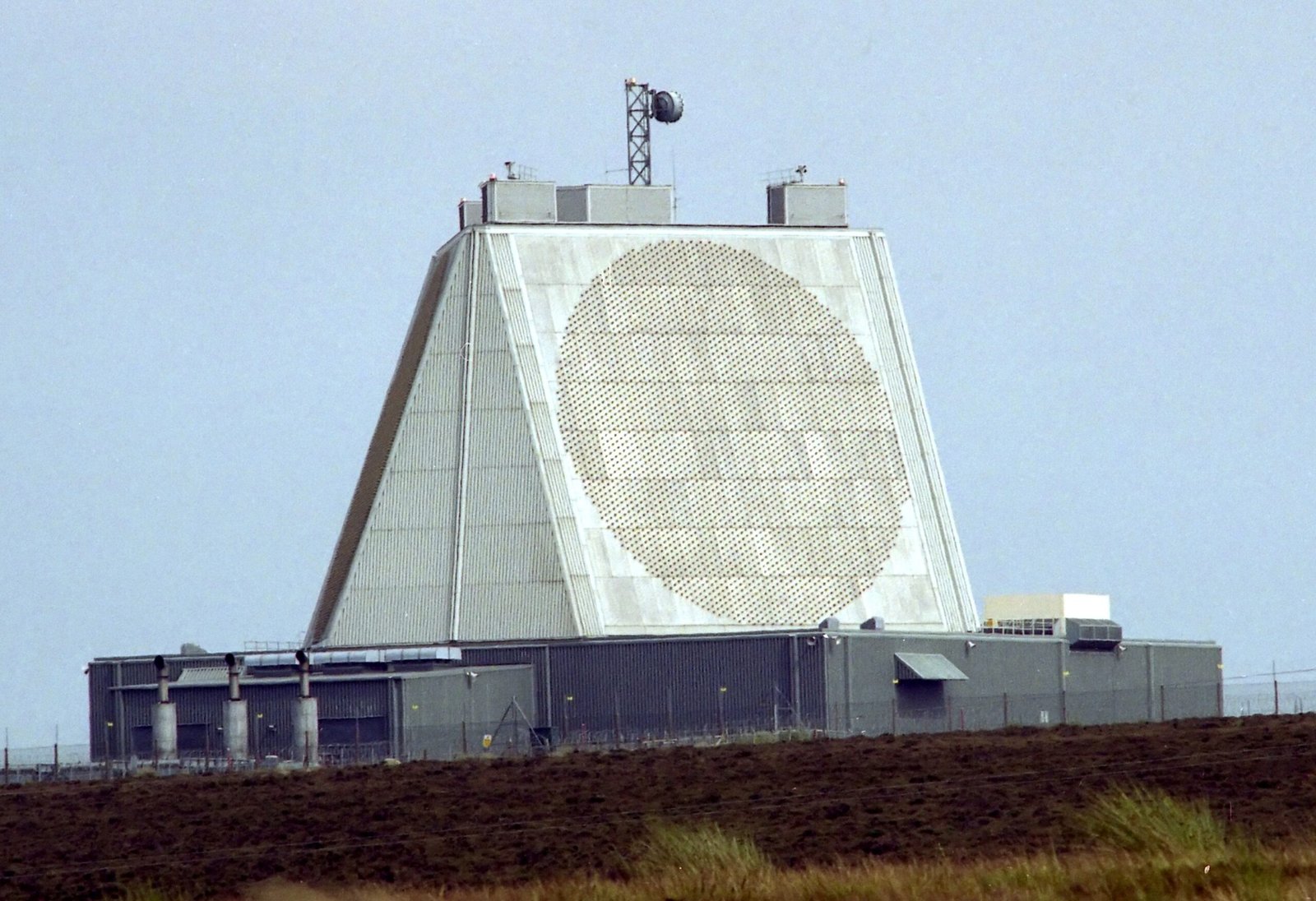

Early weather observers relied on eyewitness diaries and sketch maps, useful but blurry snapshots of violent days on the prairie. Today, mobile Doppler units and dual-polarization radars scan storms in slices, revealing pellets of debris, lofted soil, and the exact tilt of the wind. Add in drone footage and dense networks of surface stations, and the same storm is now a living CT scan, not just a silhouette. That upgrade matters because twin tornadoes are a timing problem, and timing is a data problem. When scans arrive in seconds instead of minutes, meteorologists can see a fading circulation giving way to a newborn one. The tools don’t just sharpen the image; they change the questions scientists can ask.

Anatomy of a Twin Threat

There are a few ways two funnels end up on the ground at once, and they’re not all the same beast. Sometimes the original tornado weakens as a fresh circulation tightens nearby, creating an overlap that looks like twins; that’s a cycling supercell in action. Other times a smaller, “satellite” tornado spins up on the edge of the parent’s wind field, orbiting like a moon around a planet before peeling away. There’s also storm splitting, when a single supercell divides, and the right-moving child claims the prime shear while the left mover still carries a spark. From the ground, you see two cones and feel one problem, but the wiring under the panel can be very different. That variety is why the term “double tornado” is a headline, not a diagnosis.

The Physics Few See Coming

At heart, a tornado is the atmosphere stretching a column of spin the way a skater pulls in their arms to whirl faster. In a double scenario, the storm can stretch two columns at once if the low-level winds feed more than one pocket of vorticity, or if cool outflow carves channels that focus spin. Rear-flank downdrafts – those curtains of cooler, sinking air – can either choke a tornado or sculpt the space where another one forms, a cruel kind of urban planning. The strongest cases ride sharp boundaries, where warm, moist air meets drier or cooler air and twists into ropes of rotation. A few hundred yards can decide the fate: one gust front nudges inflow to the east, another wraps around and ignites a second funnel. It’s elegant math wrapped in flying dirt.

Why It Matters

Forecasts and warnings are built around the idea that one tornado is enough trouble for one town; two multiplies the twists. Damage paths can diverge like claws, cutting different neighborhoods and confounding emergency traffic that relies on clear routes. Traditional warning polygons cover the threat area, but they rarely convey that two separate cores of destruction might exist and move differently. That matters for shelters, hospitals, and utility crews who plan staging in the gaps between storms. For scientists, double tornadoes stress-test theories about how rotation transfers from one circulation to another – a deeper check on models used for everyday forecasts. The public sees spectacle; meteorology sees a lab experiment roaring across real lives.

Global Perspectives

While the American Plains provide the most famous stage, reports of simultaneous funnels appear from Argentina’s Pampas to parts of Bangladesh, where fast-evolving storms feast on river-basin moisture. The ingredients – strong wind shear, buoyant air, and storm-scale boundaries – aren’t a U.S.-only recipe. What varies is the observation network, which means some countries likely experience these events more often than the records show. As more regions deploy better radars and crowdsourced imagery, the map of twin events is starting to fill in. It’s a reminder that the physics doesn’t carry a passport, but the data often does. Equal science access will change the story we tell about where and how often twins appear.

The Future Landscape

Next-generation phased-array radars can scan storms many times faster than today’s systems, catching the handoff between old and new circulations in near real time. Convection-allowing models are shrinking their grid spacing, pulling tornado-scale structures out of the blur and into the forecast window. Machine-learning tools trained on radar volumes, lightning flashes, and surface obs are already flagging patterns that precede quick-cycling supercells. In the field, lighter drones and safer deployment tactics may one day sample the inflow region without risking lives, turning guesswork into measured profiles. None of this eliminates uncertainty; small changes near the ground still flip outcomes like a coin. But the coin is getting heavier on one side, and that tilt helps forecasters act sooner.

How It Compares to What We Thought We Knew

Old-school thinking sometimes treated a tornado as a single, isolated machine, a standalone engine bolted to a storm. Double events force us to see the ecosystem: the storm is a city, with alleys of cool air, boulevards of inflow, and rival neighborhoods of spin. Traditional spotter guides were built around one funnel and one path, which made training simpler but missed the messier reality. Modern research reframes the hazard as a network problem – multiple nodes of rotation, intermittent bridges of debris, and quick re-routing when one node fails. That shift echoes across severe-weather science, from hail growth to flash flooding, where compound setups break old rules. We’re not throwing out the fundamentals; we’re tuning them to a busier, more tangled soundtrack.

The Road Ahead for Communities

Preparedness plans work best when they assume the second funnel, not just the first siren. Schools and factories can pre-designate secondary shelters in case the initial safe room is compromised or the second track bisects the campus. Utilities can drill on parallel outages, practicing how to isolate two damaged corridors without cascading failures. Broadcasters can add a simple phrase – two circulation centers – when radar shows the overlap, helping listeners picture the split risk. I’m a fan of neighborhood-level text groups and weather radios, a belt-and-suspenders approach that still works when towers fail. The goal is boring: fewer surprises, fewer people in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Conclusion

Start small and local: check your shelter options and make a backup plan that assumes power loss and blocked roads. If you live in a tornado-prone region, keep a weather radio, enroll in local alert systems, and practice a two-minute drill with your family. Support your regional meteorology office and volunteer networks that relay real-time ground truth during severe events. If you’re able, donate to research groups that deploy mobile radars and surface sensors; better observations today mean clearer warnings tomorrow. And when the sky turns strange, trust the science and the signal, not the rumor mill. Being ready is ordinary work that pays off on extraordinary days.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.