Walk into a forest and it feels calm, almost silent – yet beneath your feet and above your head, an intricate conversation is unfolding that most of us never notice. For decades, scientists assumed trees were mostly passive, competing for light, water, and space in stoic isolation. Now, a growing body of research suggests that forests pulse with exchanges of carbon, warning signals, and chemical messages that shape who survives, who struggles, and how ecosystems respond to stress. This emerging view has upended old ideas about trees as solitary giants and replaced them with something far stranger: a living, communicating network. The discovery is forcing researchers, foresters, and conservationists to rethink what a forest really is – and what we stand to lose if that quiet conversation is drowned out.

The Hidden Clues

One of the most surprising clues that trees might be “talking” came not from high-tech sensors, but from odd patterns in who lived and who died. In some mixed forests, seedlings of one species thrived in the shade of unrelated neighbors, yet weakened when crowded by their own kind, as if some invisible rule of spacing were being enforced. Ecologists noticed that certain “mother trees” were surrounded by rings of healthier saplings, even when no obvious physical advantage – like better soil or more sunlight – could explain it. Those saplings seemed to be plugged into something bigger than their tiny root systems. For a long time, these patterns were dismissed as quirks of microclimate or chance.

Only later did experiments reveal that carbon and nutrients could move underground between trees, often in ways that benefited young or stressed individuals. In one type of study, scientists labeled carbon in a single tree with a harmless isotope, then watched that labeled carbon appear in the tissues of neighboring trees that theoretically should have been competitors. That was a clue that something more cooperative was happening in the dark. There was no single “eureka” moment, but rather a slow accumulation of hints that, taken together, suggested forests behaved less like crowds of strangers and more like neighborhoods with shared resources and warnings.

The Underground Network: Fungi as Forest Telephone Lines

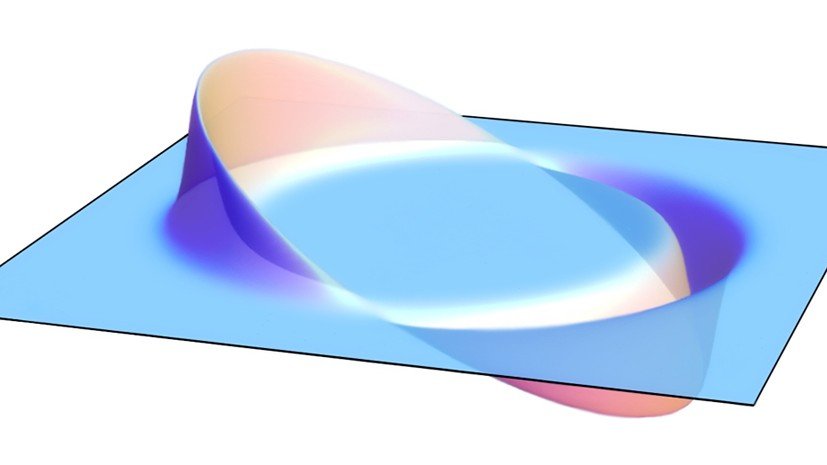

The real breakthrough came when researchers recognized the starring role of fungi – the mycorrhizal networks that thread through soil and sheath tree roots in microscopic filaments. These fungi trade nutrients with trees: they deliver water and minerals like phosphorus and nitrogen, and in return, they take a portion of the sugars trees manufacture through photosynthesis. Under a microscope, the interface between root and fungus looks almost like a set of plugged-in cables, and functionally, that is not far from the truth. Many trees in a forest are linked by overlapping fungal partners, forming what some scientists describe as a sprawling biological network.

Through this network, carbon compounds, signaling chemicals, and possibly defense cues can move from tree to tree. For example, when one tree is damaged by pests, nearby trees connected through shared fungi sometimes increase their own defensive compounds, as if they received a warning memo. Seedlings that would otherwise wither in deep shade can sometimes survive because older trees route extra carbon to them through fungal links. While not every forest uses the same types of fungi or has the same degree of connectivity, the basic pattern shows up on multiple continents and in many species. It is less like a mystical “wood-wide web” and more like a messy, evolving communications grid shaped by mutual benefit, opportunity, and, occasionally, exploitation.

The Chemical Conversations in the Air

Below ground is only half the story; forests also send messages into the air via volatile organic compounds – tiny molecules released by leaves, bark, and even roots. When insects chew on a tree’s leaves, that tree often increases its emission of specific airborne chemicals. Nearby trees of the same species, and sometimes of related species, can detect these cues and begin ramping up their own defenses before the insects ever reach them. It is akin to a neighbor seeing smoke and deciding to move their valuables before the fire spreads. These chemical plumes can drift over surprisingly long distances, creating a shifting cloud of information above the forest canopy.

These scents do more than warn other trees; they also recruit allies. Some plants emit compounds that attract parasitic wasps or predatory insects that attack the pests doing the damage. In that sense, a tree under attack is not just screaming into the void; it is placing very targeted “help wanted” ads in the chemical landscape. Humans have barely begun to decode this airborne language, but sensitive instruments already reveal that a stressed forest has a different chemical fingerprint than a healthy one. The more we learn, the more it seems that the forest atmosphere is less an empty space and more a buzzing newsroom of invisible signals.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

Indigenous communities around the world have long treated forests as living systems with agency, even before Western science had tools to probe roots and molecules. Those traditions viewed trees as responsive, interconnected beings rather than mute backdrops to human activity. For a long time, mainstream forestry brushed off such perspectives as poetic or spiritual, focusing instead on growth rates, timber yield, and individual tree physiology. Yet as instruments became more precise, some of the old intuitions about forest interconnectedness started to look strangely prescient. What once sounded like myth began to line up with measurements of nutrient sharing, synchronized flowering, and coordinated responses to drought.

Modern tools – like isotope tracing, microelectrodes, high-resolution soil imaging, and atmospheric sensors – have transformed this field from speculation into quantifiable science. Researchers can now track the flow of carbon from one tree to another, record rapid changes in electrical activity inside tree tissues, and measure subtle shifts in airborne chemical cocktails as weather or pests move through. That does not mean every claim about tree consciousness or intentional communication is supported; scientists are careful to distinguish metaphor from mechanism. But it does mean that forests are no longer treated as collections of separate units. Instead, they are increasingly studied as networks, with feedback loops and emergent behavior that might once have been dismissed as fantasy.

Why It Matters: Rethinking Forests in a Warming World

The idea that trees communicate is not just charming trivia; it changes how we think about conservation, logging, and climate resilience. If forests function as networks, then simply counting how many trees remain after cutting is not enough; the structure and connectivity of those trees matter. Removing a few large “hub” trees that support extensive fungal connections could disrupt the flow of nutrients and information for hundreds of smaller neighbors. That might leave regenerating forests more vulnerable to drought, pests, or heat waves, even if the canopy looks reasonably full from a distance. In a warming world, where extremes are becoming more frequent, those invisible support systems may be the difference between recovery and collapse.

It also reframes our role. Instead of treating forests as warehouses of carbon and wood, we start to see them as active partners in regulating climate and water cycles. When we degrade that system – through fragmentation, monoculture plantations, or soil compaction – we are effectively breaking communication lines that help forests adapt. Compared to traditional models that viewed each tree as an independent competitor, this network view demands more humility and patience. It suggests that quick fixes, like planting single-species rows for carbon credits, may miss the point. A forest that truly functions as a communicating community is harder to build – and far easier to break – than a spreadsheet of tree counts might imply.

Global Perspectives and Surprising Forest Behaviors

What is striking is how widespread, yet context-dependent, forest communication appears to be across the planet. In temperate regions, many trees rely heavily on specific fungal partners, while in tropical forests, the web of interactions is even more complex, with staggering diversity of both trees and microbes. Some dryland shrubs and trees use deep roots to tap water and then share some of that moisture and nutrients with neighbors through connected root systems. Boreal forests, dense with conifers, may depend on a smaller number of dominant fungal species that link many trees across large distances. Each biome has its own “accent” in the language of trees, shaped by soil, climate, and evolutionary history.

Researchers have also uncovered behaviors that blur the line between cooperation and competition. In some cases, trees appear to allocate more carbon to relatives than to unrelated neighbors, hinting at kin recognition. In others, parasitic plants hijack fungal networks to steal resources from their hosts, turning shared infrastructure into an access point for exploitation. These patterns show that forest communication is not some utopian harmony but a dynamic negotiation where help, selfishness, and opportunism coexist. It mirrors human networks, where the same internet can spread lifesaving information or damaging misinformation. Forests, too, run on complex economies of exchange, and there is still much we do not understand about who benefits most from the traffic.

The Future Landscape: Technology, Threats, and Possibilities

Looking ahead, new technologies are set to illuminate forest communication in almost real time. Networks of sensors are being deployed in some research forests to monitor tree sap flow, electrical activity, and airborne chemicals hour by hour, rather than in occasional snapshots. Machine-learning tools are starting to sift through mountains of data to spot patterns that human observers might miss, such as early warning signatures of drought stress or disease. As remote sensing from satellites becomes more detailed, it may even be possible to detect when entire forest regions shift their “conversation” from stable growth to crisis mode. That could give land managers precious lead time to adjust practices or intervene.

At the same time, the threats are intensifying. Climate change, invasive pests, and aggressive logging can strip away the diversity and fungal networks that make communication-rich forests possible. There is also a risk that the language of trees could be oversimplified or commercialized, turned into a buzzword to market products or justify weak conservation plans. The challenge for the coming decades is to integrate this new understanding into policy and on-the-ground practices without distorting it. Done well, it could inspire forest restoration that prioritizes soil health, species diversity, and intact mycorrhizal networks. Done poorly, it could become just another story we tell ourselves while the real conversation in the woods falls silent.

How You Can Tune In: A Quiet Call to Action

Most of us will never inject isotopes into trees or wire up a forest with electrodes, but that does not mean we are shut out of this story. Simply recognizing that forests are more than collections of trunks can shift how we behave on hikes, in parks, and at the ballot box. When you walk a trail, you are moving through an active, responsive community that is adjusting, however slowly, to your presence, the weather, and the pressures of the wider world. That awareness can make it easier to support policies that protect old-growth stands, restore degraded lands, and give forests time to rebuild their underground and airborne networks. It also makes everyday choices – like favoring products from sustainably managed forests – feel less abstract and more like an act of respect toward a living system.

If you want to go a step further, you can: support local conservation groups that focus on habitat connectivity and soil health; advocate for urban tree programs that plant diverse species, not just a single hardy favorite; or stay informed about the latest research so public debates are grounded in real science rather than romantic myths. None of these actions will “save” forests alone, but taken together, they help maintain the conditions in which the secret language of trees can keep evolving. Next time you find yourself under a canopy of leaves, you might pause and remember that what sounds like silence is, in fact, a conversation still unfolding. The question is not whether the trees are speaking – but how carefully we are willing to listen.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.