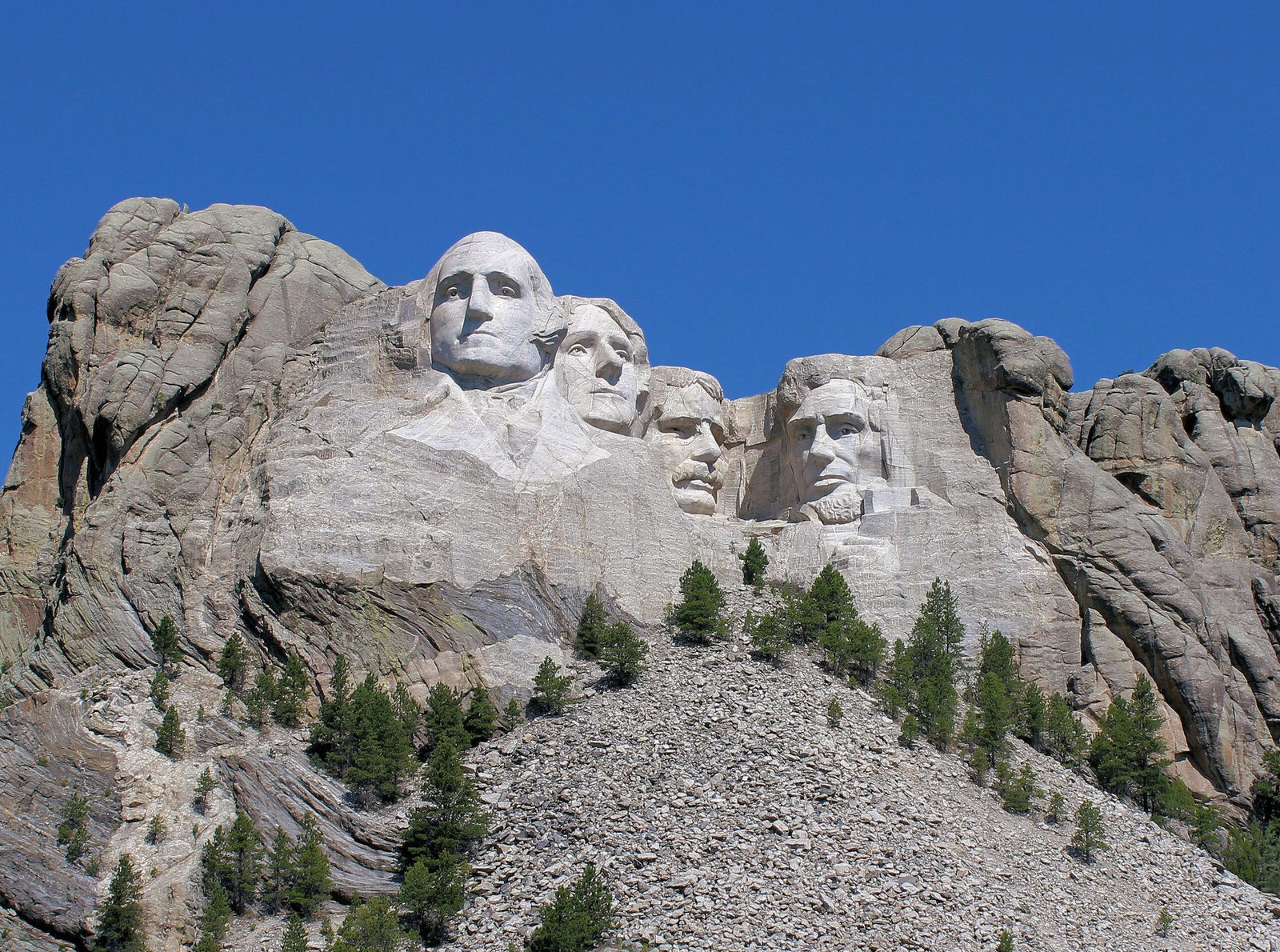

High in the Black Hills of South Dakota, colossal faces stare out across the ages—silent, majestic, and controversial. The story of Mount Rushmore is more than chisels striking granite; it is a saga filled with ambition, contradictions, and the shadows of American history. Who were the people—and forces—behind this monument? The tale is both inspiring and unsettling, a journey through artistic genius, political maneuvering, and cultural conflict. Let’s uncover the real forces that shaped one of America’s most iconic landmarks.

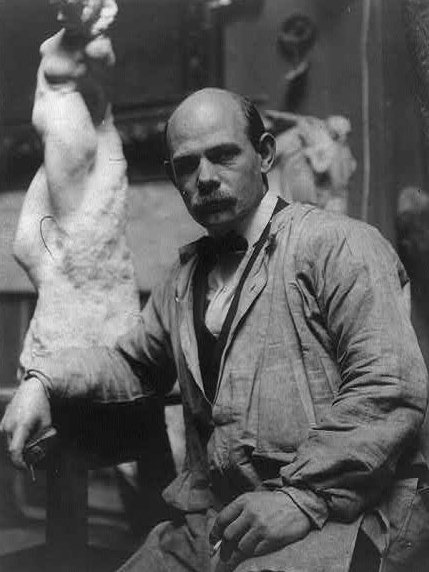

The Vision: Gutzon Borglum’s Monumental Dream

Gutzon Borglum was no ordinary sculptor. He was a man obsessed with scale, symbolism, and legacy. Born to Danish immigrants, Borglum’s early life was marked by hardship and a restless search for meaning. He had grandiose ideas, believing that art should immortalize the nation’s greatest ideals. Mount Rushmore was his attempt to carve not just faces, but the very spirit of America into stone. Driven by both patriotism and ego, Borglum envisioned a monument so vast that it would outlast centuries, capturing the attention of the world and the hearts of Americans. His vision was not just artistic, but deeply personal—a way to etch his own name beside those of presidents.

The Land Before the Mountain: The Lakota Sioux Connection

Long before any president’s face appeared on the granite, the Black Hills were sacred to the Lakota Sioux. They called these lands “Paha Sapa,” a place of spiritual power and ancestral memory. The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie had guaranteed the Black Hills to the Lakota, but the discovery of gold brought a flood of settlers and miners, leading to violent conflict and forced removal. For the Lakota, Mount Rushmore’s construction was not a celebration, but a wound—a symbol of broken promises and cultural erasure. Many Native Americans today see the monument as a stark reminder of what was taken from them.

Financing a Giant: The Political and Economic Push

Such a massive project required more than vision; it needed dollars and political will. At first, local South Dakota historian Doane Robinson dreamed up the idea as a tourist attraction, hoping to bring visitors and money to the remote region. Borglum took the concept and ran with it, expanding its scope and prestige. Funding the monument meant lobbying Congress, courting presidents, and stirring up public excitement. The Great Depression loomed over the project, threatening to stall it, but federal and private funds eventually flowed in—driven by patriotism, economic desperation, and a hunger for national pride. Every dollar raised was a small victory against the mountain itself.

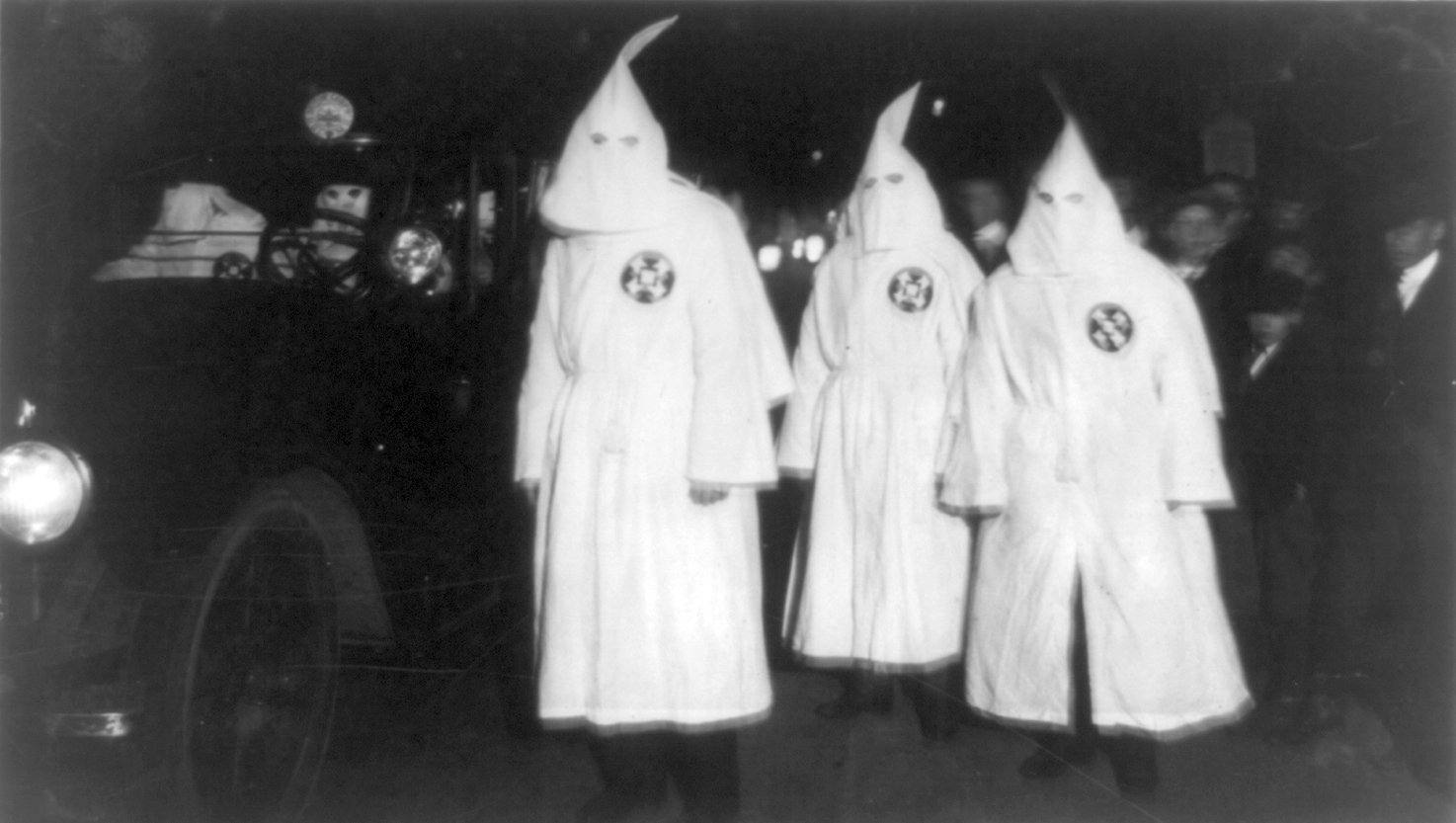

The Role of the Ku Klux Klan: A Tainted Legacy

One of the darker shadows behind Mount Rushmore’s creation is the influence of the Ku Klux Klan. Borglum had previously worked on the Stone Mountain project in Georgia, which was funded and supported by Klan members. While he left Stone Mountain after bitter disputes, his connections to Klan-affiliated donors and politicians followed him. The Klan, at the time, sought to promote their vision of American identity—an identity that excluded many. Though Mount Rushmore was not officially a Klan project, the lingering influence of these connections cannot be ignored. It adds a layer of complexity and discomfort to the otherwise triumphant narrative.

The Chosen Four: Why These Presidents?

Why did Borglum choose Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Roosevelt? Each was selected to represent a different chapter in America’s story. George Washington, the founding father, symbolized birth; Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, embodied expansion; Abraham Lincoln, the savior of the Union, stood for preservation; and Theodore Roosevelt, champion of progressivism, represented development. This selection was not without controversy. Some questioned the omission of other influential figures, while others debated the political and cultural messages these choices sent. The faces on the mountain were not just historical—they were deeply symbolic, chosen to tell a particular version of America’s journey.

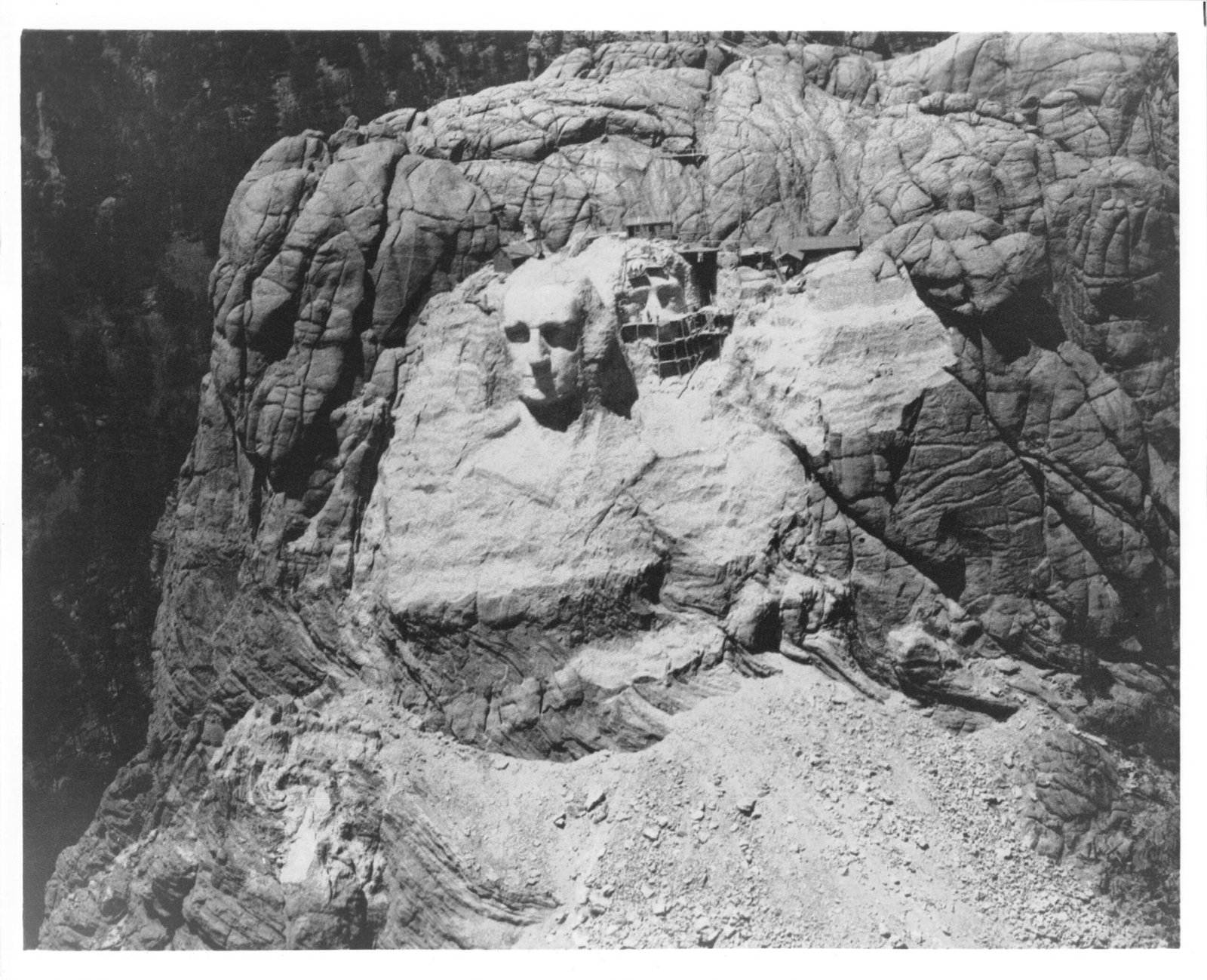

The Science of Stone: Engineering the Impossible

Carving four 60-foot faces into solid granite was a feat that seemed nearly impossible. Borglum and his team of over 400 workers faced constant technical challenges. Granite, one of Earth’s hardest rocks, demanded powerful dynamite and precise drills. Workers dangled from ropes, enduring wind, dust, and the ever-present risk of falling debris. The project became a marvel of engineering and perseverance. Decades before computers or modern machinery, these artisans used hand-drawn plans, models, and sheer grit to transform the mountain. The scientific challenges were as monumental as the artistry, blending geology, physics, and human ingenuity into every blast and chisel.

The Workers: Unsung Heroes of the Hills

While Borglum’s name is remembered, the hundreds who risked their lives on the mountain often go unmentioned. Many were local miners and laborers, seeking work during the harsh years of the Great Depression. They faced long hours, dangerous conditions, and icy winters. Some lost fingers or suffered injuries, but their commitment never wavered. Women were largely absent from the workforce, reflecting the era’s social norms. Despite the hardships, a sense of camaraderie grew among the workers—a shared pride in building something that would endure. Their collective hands shaped not just granite, but the story of human perseverance.

The Incomplete Vision: Unfinished Plans and Lasting Impact

Borglum’s original design was far more ambitious than what we see today. He dreamed of full busts, inscriptions, and even a grand hall of records behind the faces. Funding shortfalls, technical challenges, and Borglum’s death in 1941 left the monument unfinished. The mountain still holds the scars of abandoned plans—rough edges, incomplete figures, and half-finished galleries. Yet, the impact of Mount Rushmore goes beyond its physical form. It transformed the region, spurred tourism, and became a symbol woven into America’s cultural fabric—flawed, grand, and forever incomplete.

Controversy and Criticism: A Divided Legacy

Mount Rushmore’s towering presence has not shielded it from criticism. Native American activists have long protested its existence, calling for the land’s return or the monument’s removal. Environmentalists have raised concerns about the ecological impact of blasting and construction. Art historians debate Borglum’s style and intentions, questioning whether the monument truly represents American ideals. Despite its fame, Mount Rushmore remains a lightning rod—a place where debates about history, memory, and justice converge. The monument’s legacy is as fractured as the stone from which it was carved.

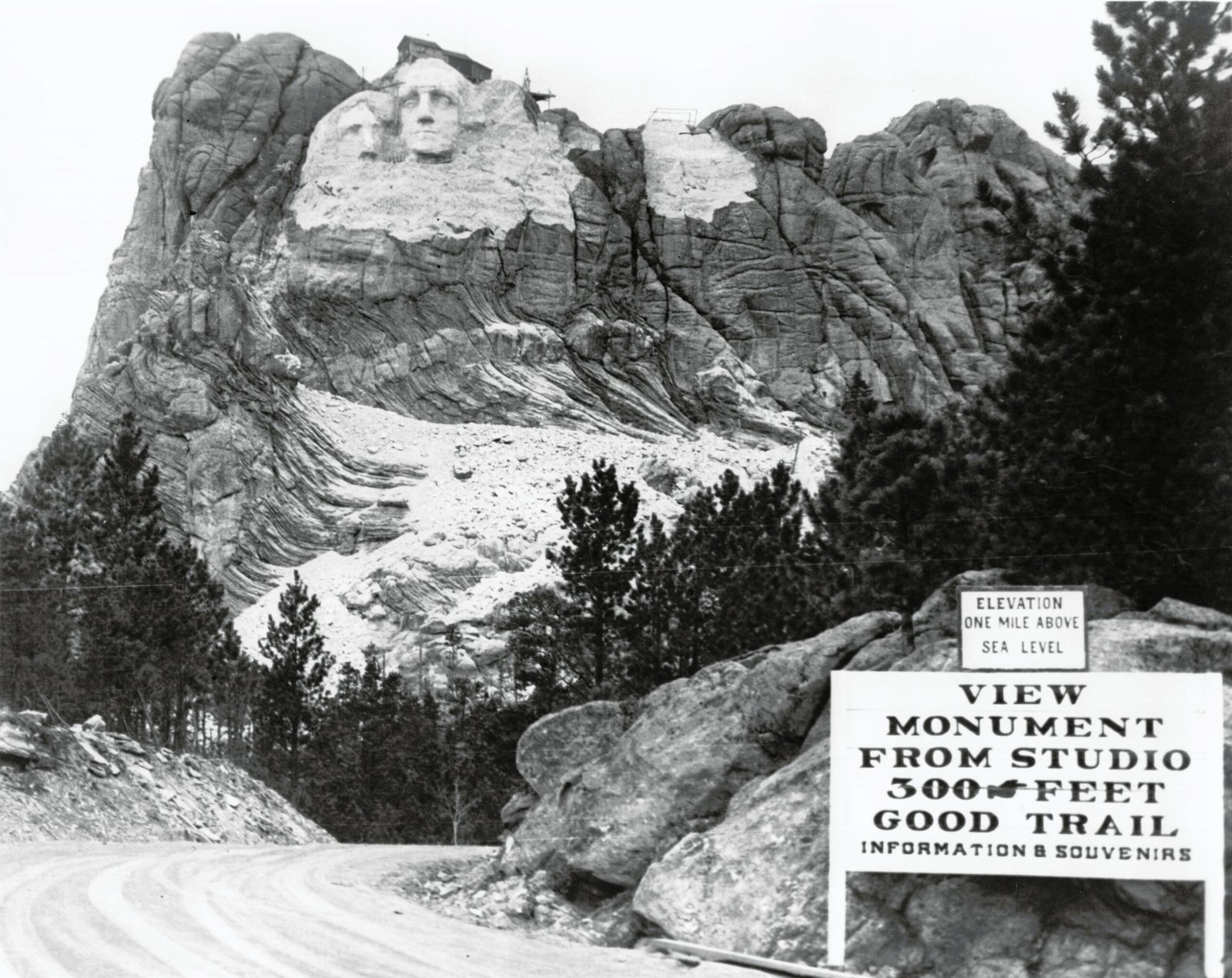

Mount Rushmore Today: A Living Symbol

Today, millions flock to the Black Hills to witness Mount Rushmore in person. The monument serves as a backdrop for celebrations, protests, and quiet moments of awe. Educational programs, light shows, and guided tours seek to tell its complex story. Some visitors see it as a tribute to democracy and bravery, while others are reminded of the pain and loss it represents. The site continues to evolve, reflecting changes in American values and understanding. The mountain, like the nation itself, is alive with meaning—layered, contested, and ever-changing.

The Enduring Question: Whose Mountain Is It?

Mount Rushmore stands as a paradox—a marvel of human achievement and a symbol of unresolved conflict. The granite faces gaze out, silent witnesses to America’s triumphs and tragedies. The question of who was truly behind Mount Rushmore has no simple answer. It was shaped by artists and workers, presidents and protesters, visionaries and skeptics. The mountain’s story is a mirror, reflecting the best and worst of the nation that carved it. As you stand before those massive visages, what story do you see staring back at you?