Happiness can feel like weather: sunny one day, overcast the next, with no clear forecast you can trust. Yet in labs from Boston to Berlin, scientists are uncovering a surprisingly structured biology behind our most elusive emotion. Brain scans, long-term cohort studies, and even smartphone experiments are revealing that joy is less random spark and more trainable brain state. That research is challenging old assumptions that happiness is either genetic fate or pure willpower. At the same time, it is raising a provocative question: if we can map happiness in the brain, can we also engineer it – ethically, equitably, and for the long haul?

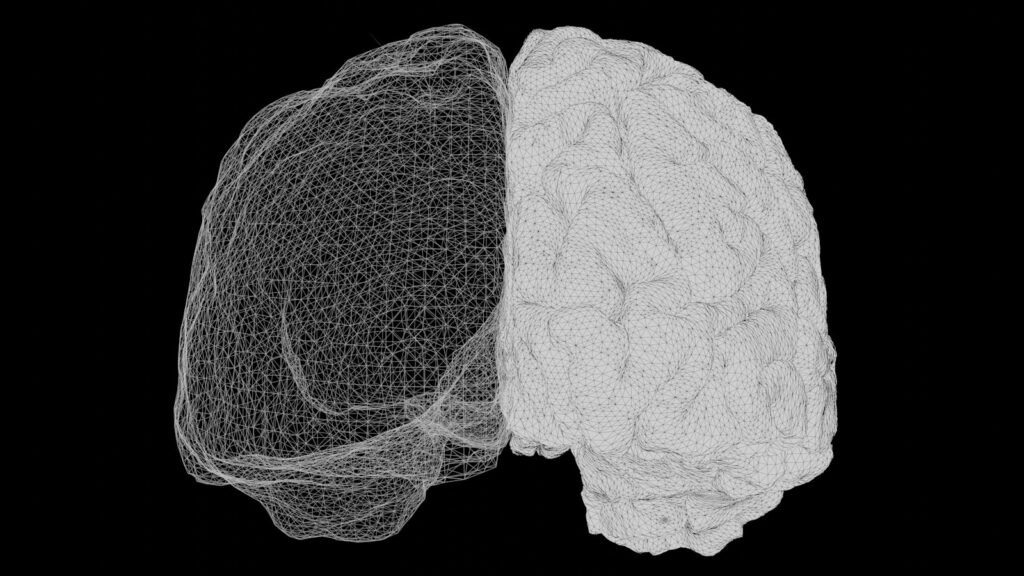

The Hidden Architecture of a Happy Brain

One of the most surprising findings in modern neuroscience is that happiness does not live in a single “pleasure center” of the brain. Instead, it emerges from a network that includes the prefrontal cortex, the striatum, the amygdala, and the default mode network, all talking to each other like a noisy group chat. Functional MRI studies show that when people report feeling content, grateful, or socially connected, activity patterns shift in these regions in distinctive ways. The prefrontal cortex, for instance, helps reframe negative events and sustain positive ones, a bit like an internal editor deciding which moments deserve a mental headline. The striatum responds strongly when we anticipate rewards, especially social or meaningful ones, not just money or food.

At the same time, the amygdala, famous for fear and threat detection, plays a quieter but vital role in dialing down overreactions and allowing safe, positive experiences to actually register. When these regions coordinate well, people tend to describe a steadier sense of well-being rather than sharp spikes of pleasure followed by crashes. Brain connectivity studies suggest that people who describe themselves as happier, on average, show stronger links between prefrontal areas and emotion-processing circuits. In practical terms, that means your sense of joy is not only about what happens to you but about how efficiently your brain’s regulatory systems can calm storms and savor bright spots.

Chemical Messengers: Beyond the Dopamine Myth

Dopamine has been branded the “happiness molecule” in countless headlines, but that label is both catchy and misleading. In reality, dopamine is more about wanting than liking: it drives motivation, anticipation, and the urge to seek rewards, from refreshing your inbox to chasing a promotion. Serotonin, another major player, helps regulate mood, sleep, and appetite, and many antidepressants work by boosting its availability in the brain. Then there are endorphins, the body’s natural opioids that surge during intense exercise or laughter, taking the edge off stress and pain. Oxytocin, released during close contact and social bonding, reinforces trust and belonging, which for many people is the backbone of lasting happiness.

Modern research paints a more nuanced picture in which happiness arises from a balanced orchestra of these molecules rather than from a single star soloist. Too much dopamine, for example, can push people toward compulsive behaviors and endless chasing of novelty, without a corresponding rise in true satisfaction. Too little serotonin can leave people vulnerable to persistent low mood and rumination, even if life circumstances look fine on paper. Some studies using brain imaging combined with genetic data suggest that individual differences in receptor sensitivity may explain why one person is buoyant under pressure while another sinks under the same load. That complexity is both frustrating and hopeful: it makes quick chemical fixes unlikely, but it also suggests many potential pathways to support healthier emotional chemistry.

From Survival Circuits to Modern Joy

If happiness feels fragile, that may be because our brains were not designed for bliss; they were built for survival in harsh environments. Evolution favored organisms that noticed threats quickly, remembered bad outcomes vividly, and stayed on alert for danger. Psychologists call this the negativity bias, and you can feel it when one harsh comment lingers longer than ten kind ones. Neuroimaging studies show that the amygdala lights up more strongly in response to negative images than positive ones of similar intensity. In other words, your brain is slightly skewed toward anxiety as a safety feature, not as a design flaw.

Yet those same ancient circuits can support joy when circumstances allow. Social bonding, play, and exploration all released survival advantages in early humans, and the brain appears to have evolved specific reward pathways to reinforce those behaviors. Today, those pathways still respond more strongly to experiences that echo our evolutionary past: face-to-face connection, shared rituals, time in nature, and a sense of contributing to a group. That is one reason a long conversation with a friend often leaves you more satisfied than an evening of doomscrolling, even if both technically count as “relaxing.” Understanding this evolutionary backdrop helps explain why some modern comforts – online shopping, ultra-processed snacks, curated feeds – hijack our reward systems without delivering deep well-being.

The Data on What Actually Makes Us Happier

For decades, happiness research relied heavily on simple surveys that asked people how satisfied they felt with life. In the last fifteen years, though, large-scale studies have started to layer that self-report data with objective measures: heart rate variability, cortisol levels, brain imaging, and even geolocation from smartphones. Longitudinal projects following tens of thousands of people across years consistently find that beyond a certain baseline of financial stability, more income adds only a small bump in reported well-being. Social relationships, mental health, and a sense of purpose repeatedly emerge as far more powerful predictors of happiness than material markers.

Some of the most striking findings come from so-called “experience sampling” studies, where participants receive random notifications throughout the day asking what they are doing and how they feel. These reveal that people tend to be happiest when they are engaged, focused, and interacting meaningfully with others, rather than when they are multitasking or mindlessly scrolling. A few robust patterns have stood out across many datasets:

- Strong social ties are associated with a notably lower risk of premature death compared with social isolation.

- Regular physical activity is linked to better mood, often rivaling the effect size of drug treatments for mild depression in some studies.

- Practices like mindfulness and gratitude journaling can produce small but reliable boosts in reported well-being over weeks to months.

Together, these findings challenge the popular narrative that happiness is mysterious or purely individual choice; there are measurable, repeatable patterns in what tends to lift humans up.

Why It Matters: The High Stakes of Joy and Well-being

The science of happiness might sound like a feel-good curiosity, but it has serious public health implications. Chronic stress and untreated depression are associated with increased risk of heart disease, diabetes, immune dysfunction, and cognitive decline. In an aging society where many people spend decades managing long-term conditions, even modest improvements in mental well-being could reshape healthcare costs and quality of life. Schools, workplaces, and governments are beginning to notice that happier people are not just nicer to be around; they are often more productive, more resilient, and less likely to burn out. When well-being is framed as a luxury or private hobby, those broader benefits are easy to miss.

Compared with traditional approaches that treated mental health purely as the absence of illness, positive psychology and affective neuroscience push for a more ambitious goal: cultivating the skills and environments that support flourishing. That includes designing cities with green spaces that reduce stress, structuring work to allow for focused time and real breaks, and embedding social connection into community planning rather than leaving it to chance. There is still debate about how far governments should go in actively “designing” happiness versus simply removing obstacles like poverty and discrimination. But the weight of evidence now suggests that ignoring the science of well-being is itself a policy choice with costs measured in lost years of healthy life and human potential.

Global Perspectives: Different Paths to the Good Life

Happiness research used to be dominated by Western, educated, relatively affluent participants, which skewed our sense of what joy looks like. Over the last decade, scientists have made a concerted effort to collect data from a wider range of cultures, and the results complicate simple stories. In some East Asian societies, for example, people place more value on calm, harmonious feelings than on the high-energy excitement often prized in the United States. Measures of life satisfaction in Nordic countries consistently rank high, but when researchers dig deeper, they find a strong emphasis on social trust, equality, and a reliable safety net rather than on individual achievement alone.

At the same time, global surveys reveal some surprisingly universal themes. Nearly everywhere, people report higher well-being when they feel safe, have at least a basic level of economic security, and trust that their institutions are not rigged against them. Social connection shows up again and again as a critical pillar, whether that takes the form of extended families, neighborhood networks, or workplace communities. Some lower-income countries score unexpectedly high on measures of day-to-day positive emotion, possibly reflecting close-knit communities and frequent informal social time. These nuances suggest that while the brain machinery of happiness is shared, the cultural scripts for using it vary, and any one-size-fits-all blueprint is likely to miss what matters on the ground.

The Future Landscape: Engineering Happiness, Carefully

The next chapter of happiness science is moving from observation to intervention, and that shift brings both excitement and unease. Researchers are testing smartphone apps that use real-time mood tracking to suggest micro-interventions: a short walk, a breathing exercise, a nudge to message a friend when your reported well-being dips. Virtual reality environments are being explored as tools for exposure therapy and for inducing awe, a state linked to reduced self-focus and greater life satisfaction. On the pharmacological front, there is growing interest in fast-acting treatments for depression, including psychedelic-assisted therapies under tightly controlled conditions. Each of these tools taps directly or indirectly into the neural circuits of emotion, sometimes with rapid, dramatic effects.

Yet the more precisely we can influence mood, the sharper the ethical questions become. Who gets access to these technologies, and who gets left behind? How do we distinguish between treating clinical suffering and enhancing normal ups and downs? There are also concerns about data privacy as happiness apps collect intimate emotional information that could, in theory, be used to manipulate behavior or sell products. Some scientists argue that the most sustainable route to better well-being still lies in slow, unglamorous changes: safer housing, fairer workplaces, stronger social protections. The future of happiness research is likely to be a tug-of-war between high-tech fixes and low-tech social reforms, with real lives hanging in the balance.

Everyday Experiments: Small Steps to Train a Happier Brain

If all this sounds abstract, the emerging science of happiness also offers concrete, testable ideas you can try in your own life. Brain plasticity research shows that repeated mental habits – like noticing what went well today or deliberately savoring small pleasures – can gradually strengthen associated neural pathways. That does not mean you can gratitude-journal your way out of serious trauma or mental illness, but it does mean that daily practices matter more than many people expect. A few interventions have shown especially consistent, if modest, benefits in randomized studies:

- Keeping a brief, weekly list of things you are genuinely thankful for.

- Scheduling regular, device-free time with friends or family.

- Engaging in moderate physical activity most days of the week.

- Practicing simple mindfulness exercises that focus on breath or bodily sensations.

None of these are magic bullets, but together they act like gentle repetitions in a mental gym.

On a personal level, I have found that the most powerful shift comes from treating happiness less like a verdict on my life and more like a skill I can practice. That mindset makes it easier to run small experiments: What happens if I walk outside during lunch every day this week? How do I feel if I intentionally text one person I care about each morning? Unlike dramatic life overhauls, these tweaks are easier to sustain and to evaluate honestly. They also make the science feel less distant, turning abstract brain diagrams into lived, daily choices. In a world that often sells happiness as a product, reclaiming it as a practice can itself be quietly radical.

Conclusion: Joining the New Science of Well-being

The science of happiness is still young, and its future will be shaped not just by researchers but by the rest of us. Many large projects now invite volunteers to track mood, sleep, movement, and social contact through apps, contributing anonymized data that helps refine our understanding of joy and distress. Supporting mental health initiatives in schools, workplaces, and local communities can push institutions to take well-being as seriously as test scores or quarterly profits. On an individual level, sharing honest stories about struggle and recovery helps chip away at stigma and opens space for more people to seek help when they need it. Even small actions, like advocating for green spaces in your neighborhood or checking in on an isolated neighbor, echo the core findings of happiness science in everyday life.

If you are curious to go deeper, consider treating your own life as a low-pressure lab, testing evidence-backed habits rather than chasing quick fixes. Notice which changes genuinely shift your mood over weeks, not just hours, and which promises turn out hollow once the novelty fades. Pay attention, too, to how your well-being interacts with that of people around you; the research is clear that happiness is contagious, both in families and in broader social networks. In a sense, by investing in your own mental health, you are quietly participating in a global experiment about what kind of lives humans can build in the twenty-first century. Given what we now know about the brain’s capacity to change, the open question is not whether happiness can be shaped, but how we will choose to shape it.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.