Trail cameras in Arizona’s Sky Islands have been quietly recording a comeback story that once felt impossible: a jaguar slipping through oak canyons and grasslands, eyes flaring in infrared, rosettes crisp as constellations. After sporadic detections in 2023 and 2024, University of Arizona researchers confirmed a flurry of sightings this summer of a single male roaming south of Tucson, suggesting the borderlands still function as a living corridor. State biologists also verified a previously unknown jaguar in the Huachuca Mountains, adding to the small but growing list of cats documented in the U.S. Southwest since the mid‑1990s. In a region wrestling with border barriers and drought, the images land like a plot twist: the habitat hasn’t given up yet, and neither have the cats.

I remember hiking a wash in the Santa Ritas years ago, scanning dust for prints and telling myself I’d be happy just to see a coati; now the evidence for jaguars is no longer mythical, it’s memory card real. The mystery is turning into a testable hypothesis – one that science is racing to understand and protect.

The Hidden Clues

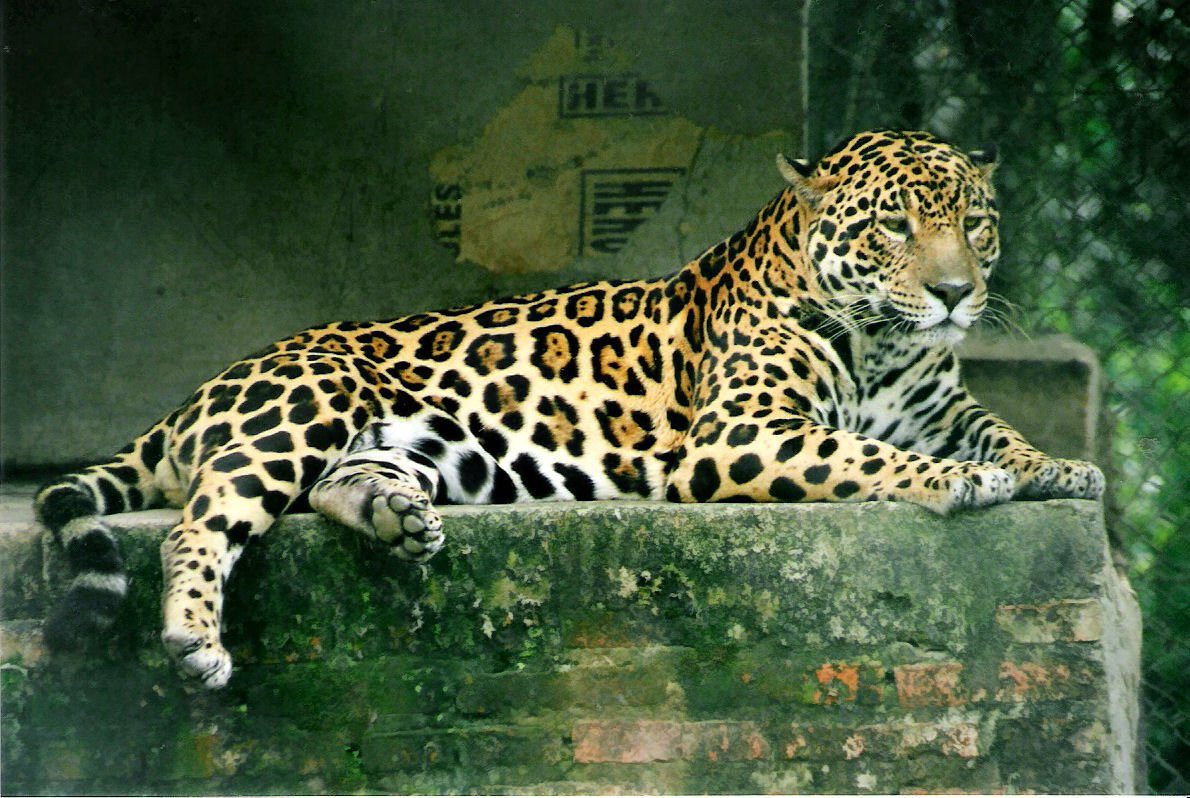

Jaguars announce themselves with patterns – the teardrop rosettes that function like fingerprints – and those are what researchers scrutinize frame by frame. A new cat in the Huachucas early in 2024 was confirmed by comparing its coat to known individuals, a forensic exercise built on thousands of photos and meticulous catalogs. That same logic underpins this year’s detections by University of Arizona teams, who recognized a returning male by his spot map across multiple sites. The process isn’t romantic; it’s data science with mud on its boots, and it’s the reason we can say with confidence that these are not recycled ghosts from old headlines. On a good day, a single night‑vision clip can untangle months of uncertainty and redraw the map of where conservation efforts should focus. The stakes of each clip feel outsized because, for now, every individual in Arizona matters.

Those confirmations matter historically, too. The Southwest has only tallied a handful of unique jaguars since the 1990s, so each verified sighting shifts baselines that used to say “never” into baselines that now say “not yet.” When the math is this sparse, one new data point becomes a story, and a cluster of them becomes a trend. That’s how hope gets quantified in wildlife biology: not in adjectives, but in repeat detections.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

For generations, trackers relied on old‑school fieldcraft – reading heel marks in sand, weighing the stride of an animal against the shape of a canyon. Today those skills blend with machine learning that flags rosette patterns, genetic assays that identify species from a fleck of scat, and time‑synced camera grids that operate like a distributed observatory. University of Arizona teams have even used lab analyses to verify jaguar scats in earlier projects, connecting images to hard DNA evidence. Layered together, these methods convert a landscape into a sensor-rich lab and turn rare encounters into a repeatable monitoring program. That’s not just clever; it’s the difference between anecdotes and management decisions.

The results are more than pretty photos. They feed occupancy models, inform corridor maps, and help agencies decide where to target protection. By comparing detections across cameras and seasons, researchers can test whether cats are funneling through certain passes or experimenting with new routes. When patterns persist, proposed corridors move from aspiration to infrastructure, and funding can follow the evidence.

The Sky Islands Effect

Arizona’s Sky Islands – a necklace of isolated mountain ranges rising from desert – create a stairway of habitats from cactus flats to fir forest. That vertical variety packs prey, shade, and water into tight spaces, letting tropical species like jaguars meet temperate species on common ground. The San Rafael Valley and nearby ranges serve as the last broad, relatively open bridge to breeding populations in Sonora, Mexico, which is why every crossing matters. It’s a landscape that looks delicate but functions like a hinge, swinging species north and south with seasons and storms. The recent run of detections suggests that hinge still moves; the corridor isn’t theoretical, it’s working in real time.

There’s a human lesson embedded here. A few years ago, removal of makeshift shipping-container barriers reopened a well‑known wildlife pinch point, and detections followed. That doesn’t prove cause and effect, but it does echo what corridor science predicts: when you stop pinching, movement resumes. In a drought‑stressed region, keeping those doors ajar can be the difference between a species remaining a visitor or becoming a neighbor again.

A Borderland Comeback?

Biologists emphasize a sober fact: nearly all jaguars live far to the south, and breeding has not been recorded in the United States in more than a century. The cats appearing in Arizona are most likely pioneering males dispersing from Sonora, testing the edges of their historical range. That’s exciting and fragile at once – pioneers blaze trails, but without females, populations don’t anchor. The science case is straightforward: protect the corridors, safeguard prey and water, and keep the door open long enough for females to follow. If that happens, numbers could grow from occasional blips to seasonal presence, and then to something resembling residency. Each year of detections makes that scenario a little less speculative.

Coexistence efforts in Sonora offer a practical model. On ranchlands south of the border, camera‑based incentive programs have paid landowners when jaguars appear on their properties, aligning livelihoods with conservation. Those programs have expanded protected acreage around a core reserve and, just as importantly, shifted local attitudes from conflict to stewardship. If similar pragmatism scales across the borderlands, jaguars gain time and space to return on their own power – no translocations required.

Why It Matters

The return of an apex predator is a stress test of an ecosystem’s integrity. Where jaguars travel, prey communities are usually intact, riparian thickets still carry water, and the food web can support a heavyweight hunter. Compared with managing single‑species crises, restoring a corridor that serves jaguars also benefits mountain lions, black bears, ocelots, pronghorn, and the seed‑dispersing animals they depend on. The science payoff is broad as well: long‑distance movements reveal how climate pushes species across political borders, and how infrastructure either blocks or bends that flow. As a reporter who’s watched conservation fads flare and fade, this one stands out for its humility – let the cats decide with their feet, and follow the data.

Contrast that with a more traditional approach that waits for breeding pairs before acting, only to discover it’s too late to reconnect habitat. Corridor-first strategies invert that timeline: secure the path now, and biology can catch up later. It’s a cleaner experiment, and the results are already showing up on camera screens.

Global Perspectives

Even in a good year, Arizona’s jaguars are the northern margin of a species whose strongholds are in Mexico, Central America, and South America. That context matters because conservation here rides on cooperation there; if Sonora’s population thrives, the U.S. will continue to see adventurous males, and eventually, perhaps, females. Agencies also remind us that the most persistent threats are old and global – habitat loss and fragmentation, retaliatory killing over livestock, and, in some places, illegal trade. The borderlands simply compress those pressures into a narrow strip of land where every decision echoes across two countries. The science isn’t parochial; it’s a case study in transboundary conservation.

Policy has adapted, sometimes painfully. After court-ordered revisions in 2024 reduced Arizona’s designated jaguar critical habitat, managers doubled down on partnerships and monitoring to keep potential pathways viable. Critical habitat is a tool, not a guarantee, and the cameras are showing where its lines still align with reality – and where they might need to shift.

The Future Landscape

The next few years will be decisive because steel and law move quickly. DHS has awarded contracts and issued waivers to speed roughly two dozen miles of new barrier in southern Arizona, including stretches that conservationists say slice through the San Rafael Valley – one of the last wide doors for north–south wildlife movement. Engineers can design wildlife‑friendly features, but tall bollards set inches apart are not friendly to a cat with a wide chest and a low appetite for squeezing. If construction proceeds without permeability in the right places, the corridor could narrow from a highway to a cul‑de‑sac. That would strand any U.S. jaguar from mates and genetic exchange across the border, undercutting the very mechanism that has brought them back. ([cbp.gov](https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/national-media-release/dhs-awards-contract-27-miles-new-border-wall-arizona-issues-waiver?utm_source=openai))

There’s another path. Smarter networks of AI‑assisted cameras, satellite moisture maps that predict water and prey, and cross‑border ranching incentives can keep movement possible even as development grows. Agencies could pilot targeted openings in existing barriers at seasonal pinch points, guided by data rather than politics. The ingredients are already on the table; what’s missing is the decision to treat wildlife movement as essential infrastructure. The jaguar is simply the most charismatic messenger for a message countless species are sending.

How You Can Help

Start local: if you hike or run cameras in southern Arizona, avoid sharing exact locations of sensitive detections and report credible evidence to Arizona wildlife authorities instead of social media. If you’re a landowner, consider programs that compensate for camera detections or help harden livestock operations, which can reduce conflict and keep tolerance high. Support organizations on both sides of the border that buy time and space for wide‑ranging wildlife, from corridor mapping to rancher partnerships.

Stay engaged with public comment periods on projects in border counties, where a handful of voices can shape where, how, and whether barriers are built. And if you’re lucky enough to see a rosette flicker on a screen, remember: restraint is a conservation act, too.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.