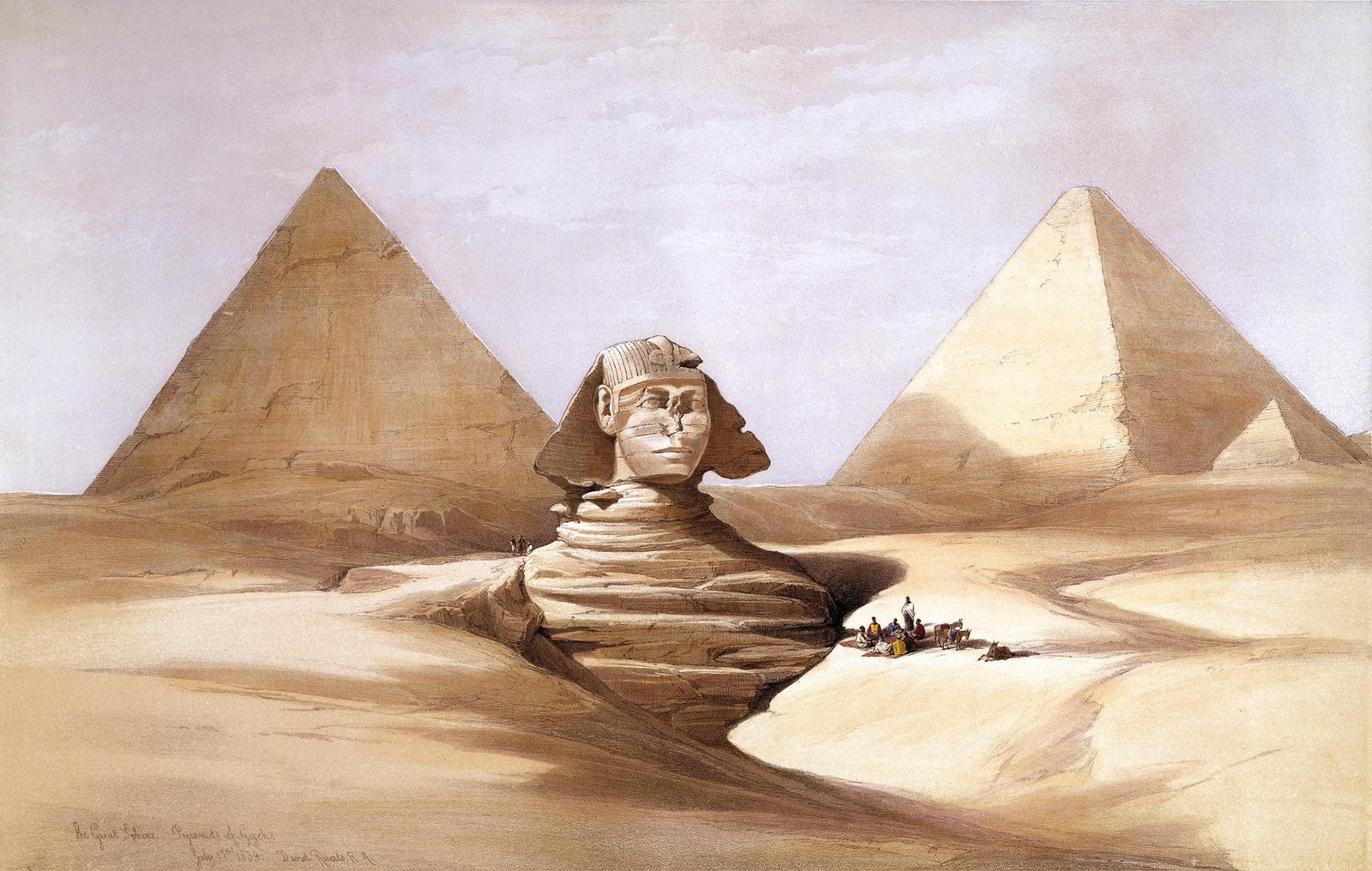

The pyramids have long been framed as an unsolved riddle, but the picture is finally sharpening into focus: a story of clever logistics, stubborn materials, seasonal labor, and river-borne engineering. Over the past decade, archaeologists and physicists have uncovered decisive clues – from ancient logbooks to particle scans – that replace speculation with testable models. Instead of miracle machines or lost technologies, we see a civilization that mastered water, sand, stone, and time. This shift doesn’t make the pyramids less astonishing; it makes them more human, and more impressive. The mystery hasn’t vanished, but the blank spaces on the map are shrinking fast.

The Hidden Clues

What if the real answers were hiding in plain sight – in graffiti, tool marks, and dusty ledgers? Inside the Great Pyramid’s upper chambers, painted quarry marks name work crews tied to Khufu, anchoring the monument to a real workforce with real supervisors. At Giza’s worker village, bakeries, breweries, and barracks reveal a planned logistics hub that could feed thousands on rotating shifts. Far from mythology, these are fingerprints of an organized construction economy. They read like a project binder from antiquity, not a magic trick.

Even more decisive is a set of papyri from the Red Sea, where an overseer recorded boat deliveries of fine limestone to “the Horizon of Khufu.” Those sheets connect quarry, river, and building site like dots in a join-the-dots puzzle. Add to that chisel scars, dolerite pounding pits, and unfinished quarries, and you get a chain of evidence you can walk on. Each mark narrows the gap between “maybe” and “here’s how.”

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

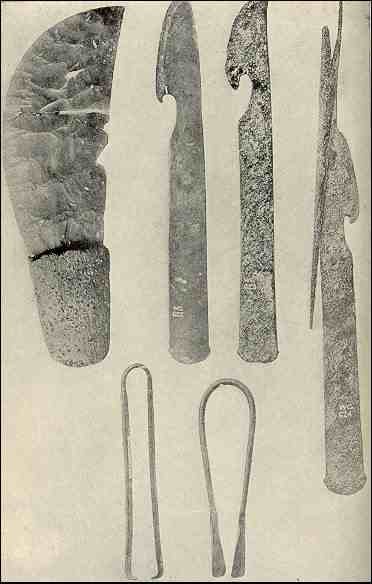

Egyptian builders weren’t swinging bronze age magic; they used copper chisels, stone pounders, wooden sledges, and rope – and knew exactly how to work within those limits. Copper is soft, but limestone is softer, and frequent sharpening turns a humble chisel into a reliable production tool. Dolerite – the tough black stone you can still find scattered in ancient quarries – did the brute work of roughing granite faces. Meanwhile, surveyors used sighting tools, plumb bobs, and leveling channels to set lines straighter than a stretched bowstring. Their secret wasn’t exotic metal; it was method.

Modern science is reading these methods like a palimpsest. Muon radiography has mapped hidden voids and a narrow corridor above the Great Pyramid’s entrance without touching a stone, while microscopic studies of tool marks distinguish pounding from cutting. I once watched a conservator anneal a copper chisel and drive it into a block of soft limestone; it dulled fast but bit cleanly, exactly as the archaeology predicts. When field experiments rhyme with the artifacts, confidence rises. The past starts to feel less like guesswork and more like engineering.

From Quarry to Site: Water, Sand, and Sledges

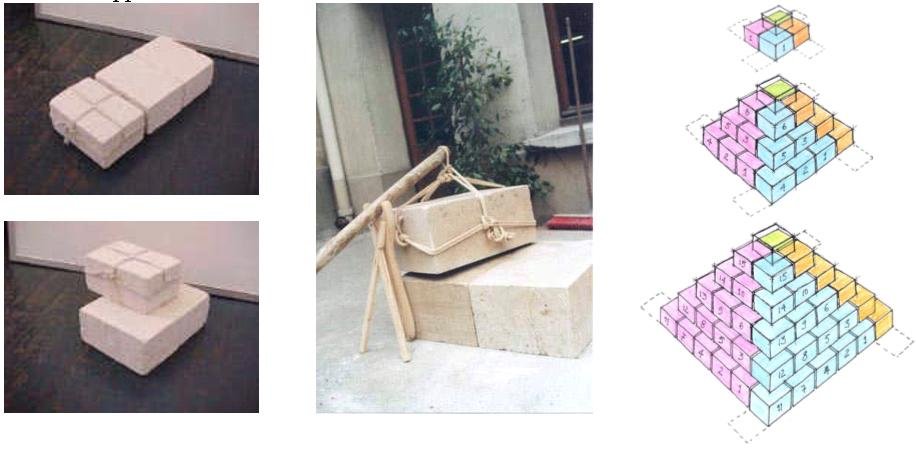

Moving multi-ton blocks sounds impossible until you turn the desert into a machine. Workers quarried limestone locally and prized white casing from Tura across the river, then loaded it onto boats during higher Nile levels. A now-vanished branch of the Nile likely reached closer to the Giza plateau than the river does today, shortening the overland haul. From that riverside harbor, causeways and compacted tracks guided sledges toward the rising pyramid. It’s a choreography of water and ground pressure, not brute chaos.

And here’s the wonderfully simple trick: slightly wet sand. Lab tests and practical trials show that dampening desert sand can dramatically cut the force required to drag a sledge, stiffening the grains so they flow less and grip more. Add a wooden runner, a slick of water, and teams working in rhythm, and the friction problem loses its mystique. The image of workers pouring water before a sledge, once seen as ceremonial, now reads like a field manual. Physics, it turns out, was the foreman.

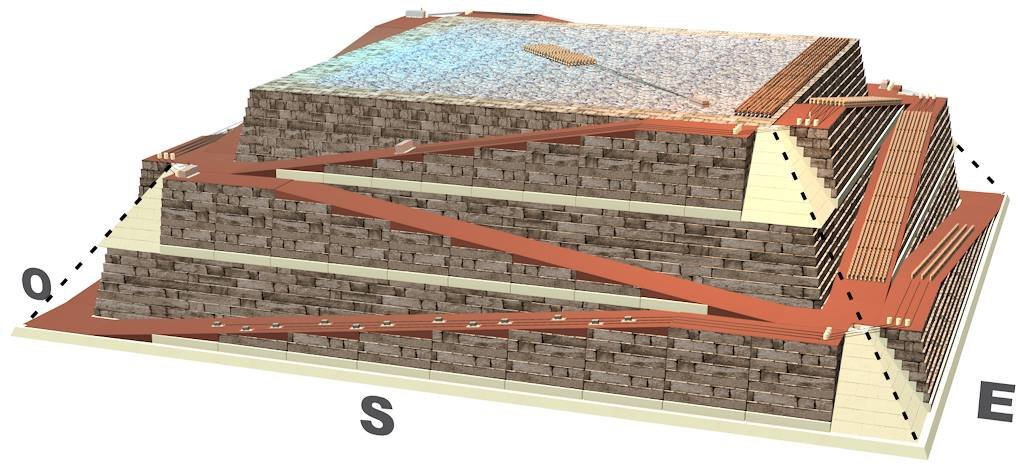

Ramps, Levers, and Counterweights

The ramp debate – straight, zigzagging, spiral, or internal – isn’t a fight between right and wrong so much as a question of combination and phase. Early stages favor broader ramps for mass delivery; later stages demand tighter systems as the pyramid rises and space narrows. Evidence from an Old Kingdom quarry shows a steep ramp with side posts likely used for ropes and sledges, hinting at high-angle hauling with mechanical advantage. On the pyramid itself, short ramps, platforms, and lever stations would have taken over as crews lifted blocks course by course. Think modular, not monolithic.

Simple levers are underrated heroes here. A few centimeters at a time, a well-placed pry bar can walk a block upward onto the next course, especially when paired with cribbing and chocks. Counterweights – bags of sand or stones – could smooth starts and stops, reducing peak strain on rope fibers. No pulleys, no steel, just clever sequencing and lots of safety margins. The elegance lies in the staging, not in any single miracle device.

The Labor Force Behind the Stones

The workforce was skilled, organized, and – crucially – not enslaved in the way pop culture suggests. Archaeological evidence points to paid crews who rotated in and out seasonally, housed near the site and compensated in bread, beer, and meat. Healed fractures and medical care in workers’ cemeteries show a society investing in its builders rather than burning them out. Teams were divided into named units, a morale-boosting identity you can still see in inscriptions. This wasn’t punishment; it was national service with prestige.

Management mattered as much as muscle. Scheduling deliveries with the river, marshalling animals and water carriers, and distributing tools demanded planners who could count, forecast, and adapt. Standardized block sizes in certain zones hint at batching and quality control. When thousands of hands move like one machine, small efficiencies compound into monumental progress. That’s the quiet genius often missed in the headline myths.

Why It Matters

Understanding how the pyramids were built isn’t trivia; it’s a masterclass in sustainable logistics and human problem‑solving. The builders exploited seasonal cycles – high water for transport, cooler months for heavy labor – rather than fighting them. They optimized local materials and low-tech tools, squeezing performance from physics instead of burning exotic fuels. In a world hunting for lower‑carbon construction methods, that mindset feels surprisingly modern. The lesson is less about stones and more about systems.

There’s also a cultural cost to myth-making. When we credit aliens or lost supertech, we erase the ingenuity of real people whose names still echo in faded paint. Solid evidence – tool marks, papyri, worker villages, scanned corridors – replaces spectacle with respect. It also sharpens our broader science: reconstructing ancient river levels, modeling friction in granular materials, and refining noninvasive imaging all spill into other fields. The pyramids are a gateway, not a cul‑de‑sac.

The Future Landscape

The next breakthroughs will come from patient, noninvasive tech layered with careful fieldwork. Improved muography will resolve voids with finer detail, while ground‑penetrating radar and microgravimetry map subtle density changes without drilling. High‑resolution photogrammetry and lidar are building living “digital twins” of the plateau, so hypotheses about ramp placement or work staging can be tested in virtual space before anyone moves a pebble. Materials scientists are also decoding ancient mortars, salts, and weathering layers to understand long‑term durability. Each discipline adds a missing gear to the old machine.

Big questions remain: the exact staging of upper courses, the full extent of harbor infrastructure, and the precise division of labor across seasons. The challenge will be balancing curiosity with conservation; every invasive test must prove its value. Cross‑border climate data may also reshape the timeline, as Sahara wind and Nile hydrology reconstructions get sharper. Expect fewer grand revelations and more steady accumulation, the scientific equivalent of laying one well‑fitted block after another. That’s how these monuments were built, and how their story will be finished.

Conclusion

Support institutions that publish open, peer‑reviewed research and share high‑quality scans and models – those resources let anyone follow the evidence, not the hype. When you see sensational claims, ask for the chain of proof: artifacts, measurements, and methods that other teams can replicate. Visit museums that invest in conservation and education, and consider backing field schools that train the next generation of archaeologists and conservators. If you’re an educator, bring the physics of sand, water, and levers into the classroom; a small sledge on dampened sand can spark a lifetime of curiosity. The pyramids deserve admiration, but even more, they deserve understanding – are you ready to move from marveling to knowing?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.