Across river valleys and flat-topped hills from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast, earthen monuments rise just high enough to be missed by a hurried glance – but not by today’s science. For generations, the story of these mounds was patchy, dimmed by erosion, farming, and old assumptions. Now a wave of new tools is peeling back the ground without turning a shovel, revealing planned cities, vast trade webs, and carefully aligned ceremonial landscapes. The picture emerging is not of isolated dirt heaps, but of engineering feats that reshaped terrain and time. The mystery isn’t vanishing; it’s getting sharper, and that’s what makes this moment electric.

The Hidden Clues

Some of the oldest monumental complexes in North America are made of earth – humble material hiding sophisticated design. When you look with modern eyes, faint rises in pastureland resolve into geometric embankments, processional avenues, and leveled plazas. Subtle ditches become water-management features, not random scars. In places once dismissed as “natural knolls,” patterns repeat with intent, hinting at calendars, ceremonies, and city planning.

What changed is not the ground – it’s our ability to read it. By layering high-resolution elevation models, soil chemistry, and vegetation signatures, researchers can spot the faint fingerprint of a long-buried platform mound or causeway. The clues were always there; the language to interpret them finally caught up.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

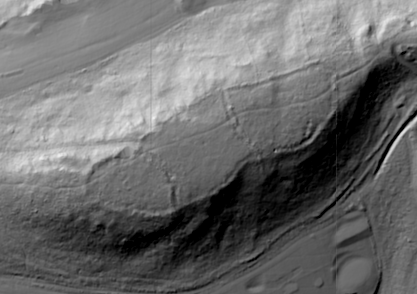

Archaeologists now fly lasers over forests and fields, using airborne LiDAR to strip away tree canopies and reveal microtopography with astonishing precision. Ground-penetrating radar and magnetometry trace subsurface walls, pits, and hearths, letting teams map entire sites in days rather than seasons. Drone photogrammetry stitches thousands of images into true-to-scale 3D terrain, while Bayesian models refine radiocarbon dates into tight timelines. Even optically stimulated luminescence helps estimate when mound sediments last saw sunlight.

These methods are paired with minimal or no excavation, a critical shift that respects culturally sensitive places. The result is a kind of archaeological MRI: a layered, noninvasive view that captures planning decisions – terrace by terrace, plaza by plaza – without lifting a trowel. It’s efficient, precise, and kinder to the record we’re trying to protect.

Unraveling Timelines

New dating frameworks show mound building stretching back thousands of years, deep into the Archaic period, long before metalworking or Old World-style agriculture. Later, across the Woodland and Mississippian eras, construction surged and diversified, from conical burial mounds to massive platform mounds anchoring broad plazas. Instead of a single “mound culture,” the record shows many traditions, adapted to local ecologies and social needs.

Chronologies that once looked like scattered dots now form meaningful arcs. As dates tighten, archaeologists can trace site expansions, pauses, and rebuilds tied to floods, droughts, or leadership change. A living timeline is replacing a static one, and it’s unexpectedly dynamic.

Landscapes as Text

These earthworks are not stand-alone monuments; they’re sentences within larger geographic stories. Causeways link platform mounds to plazas, while embankments frame views of the horizon and sky. In some complexes, alignments key to solstices or complex lunar cycles hint at sky-watching knowledge encoded in soil and slope. Water channels, borrow pits, and terraces show people engineered both ceremony and drainage with equal care.

Think of entire valleys as libraries where sightlines, distances, and elevations are the script. When researchers model visibility and acoustics, new meanings emerge: where crowds would gather, where leaders would speak, where processions moved at dawn. The land becomes the archive, and reading it requires both science and empathy.

People, Trade, and Power

Chemical and isotopic signatures are rewriting the social map of mound centers. Copper traced to the Great Lakes, mica from the Appalachians, and marine shell from the coasts speak to networks spanning great distances. At some sites, strontium and oxygen isotope values point to both locals and newcomers, suggesting migration or pilgrimage to ceremonial hubs. That complexity mirrors the labor it took to move millions of baskets of soil, season after season.

Power, it turns out, often looked like stewardship: coordinating water, food, and ritual over time. And those monumental plazas? They weren’t empty stages but engines of community – places where exchange, diplomacy, and memory thickened into identity.

- Materials moved across regions, signaling wide exchange networks.

- Isotope studies reveal people with different childhood geographies at single sites.

- Monumental labor implies leadership and shared purpose, not just coercion.

Why It Matters

For too long, the story of ancient North America was treated like a footnote to more familiar stone temples overseas. The mounds dismantle that bias: they represent large-scale planning, scientific observation, and social coordination carried out in earth rather than masonry. Recognizing that sophistication changes how schools teach, how museums interpret, and how communities value nearby ridges and rings. It also corrects the record by centering Indigenous ingenuity and continuity.

Compared with past methods – heavy excavation and narrow trenches – the current approach produces faster, broader, and more respectful insights. The payoff is practical: better site management, better flood and erosion planning, and better collaboration with descendant communities. The stakes aren’t abstract; they affect land use, heritage policy, and the stories we pass on.

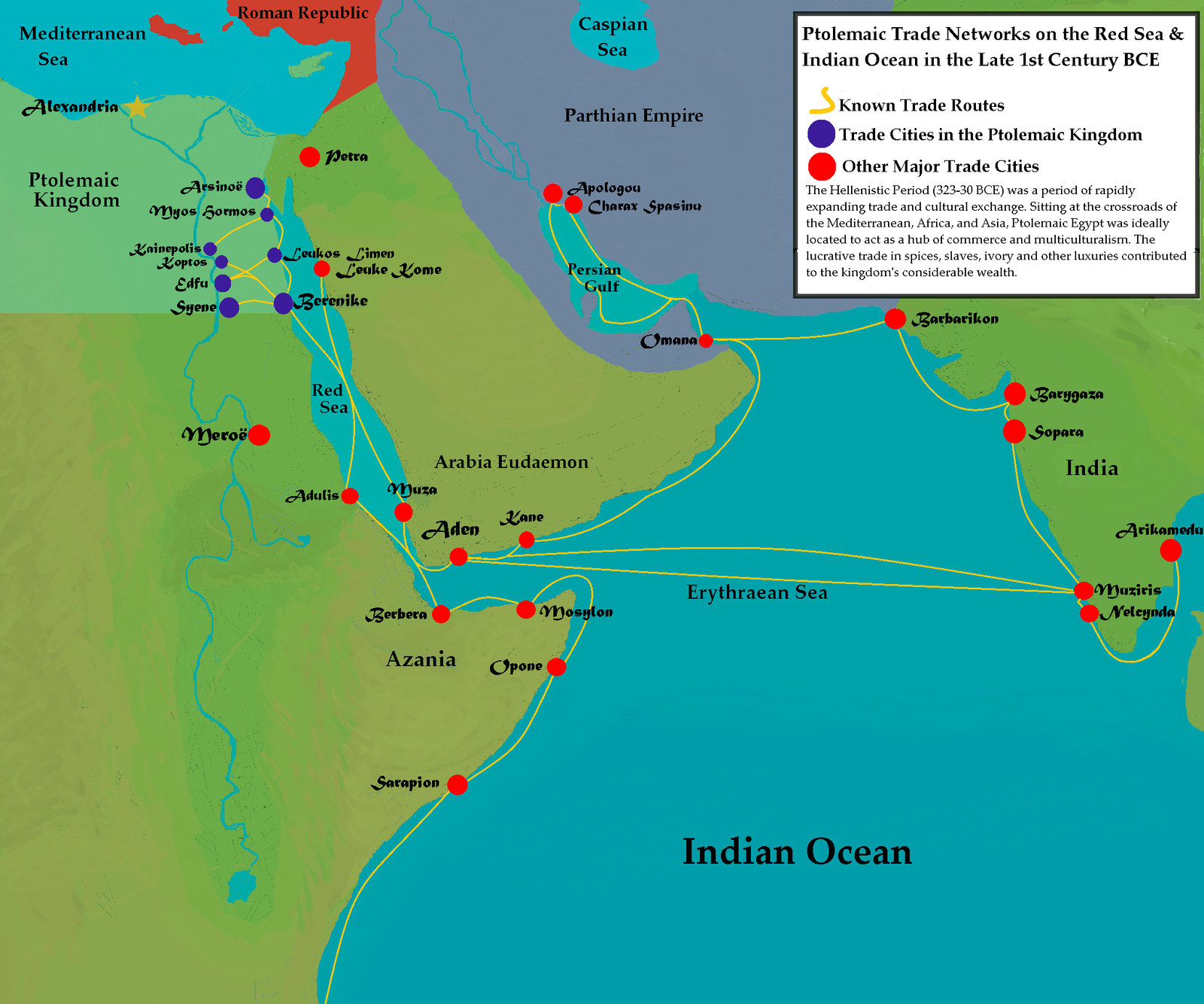

Global Perspectives

America’s mound traditions fit into a worldwide conversation about earth as an intentional building medium. From Andean terraces to Eurasian earthen ramparts, soil architecture is both adaptable and resilient. What’s distinctive in North America is how astronomy, hydrology, and civic space converge in vast, low-slung forms that integrate with wetlands, prairies, and river bends. The scale is continental, yet the engineering is delicately tuned to local conditions.

This comparison cuts both ways: insights from North American earthworks help researchers revisit other earthen monuments abroad with fresh questions. How do alignments persist across rebuilds? Where does water engineering blur with ceremony? The answers cross borders even when the mounds do not.

The Hidden Science of Erosion and Survival

Earthen monuments endure because they were knowingly layered, compacted, and sometimes capped with clay to shed water. Micro-erosion mapping shows places strengthened by added soils and turf, suggesting maintenance was part of monument life. Where plows bit deep, LiDAR still salvages outlines, letting teams model original shapes and volumes. Even agricultural scars, once purely destructive, now offer data about soil movement and mound construction sequences.

Climate adds urgency: heavier rains, shifting floodplains, and vegetation change expose fragile slopes. By modeling runoff and root damage, archaeologists and land managers can target stabilization where it matters most. Survival is no accident; it’s a partnership between ancient design and modern care.

The Future Landscape

Next-generation surveys will fuse LiDAR, hyperspectral imaging, and satellite radar into constantly updating digital twins of mound landscapes. Machine learning can flag likely features across entire watersheds, turning weeks of field scanning into hours of triage. Portable geophysics is getting lighter and faster, ideal for community-led mapping days. Meanwhile, refined dating – combining radiocarbon, luminescence, and stratigraphic modeling – will sharpen construction chronologies to human timescales.

The biggest challenge isn’t just technical; it’s ethical. Co-stewardship with Tribal Nations, respectful data governance, and careful handling of sensitive locations must shape every step. If done right, the next decade will produce richer science and stronger relationships – proof that knowledge and care can advance together.

Conclusion

You can help protect this layered history without leaving footprints on fragile ground. Visit public sites that welcome guests, follow posted paths, and support local parks that maintain trails and signage. If you live near low rises or odd rings in fields, consider reporting them to state archaeologists rather than exploring on your own. Classroom teachers can fold mounds into science units on engineering, ecology, and astronomy to widen the lens for the next generation.

Consider volunteering with preservation groups that clear invasive plants or help with noninvasive survey days. And when land-use debates surface, speak up for heritage alongside housing, farms, and flood safety. The future of these places is a shared project – measured in seasons, but meaningful for centuries.

Sources:

- National Park Service: Ancient Earthworks of the Eastern United States

- Smithsonian Institution research on North American mound complexes

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.