Time moves differently on a glacier. What feels like moments to us spans millennia in the ice beneath our feet, where snowflakes that fell centuries ago still tell their stories. But here’s what’s chilling – and I don’t mean the temperature – scientists are now racing against melting clocks to rescue these frozen libraries before climate change erases them forever. Picture this: researchers drilling frantically into glaciers worldwide, not searching for oil or minerals, but trying to save the very memory of our planet.

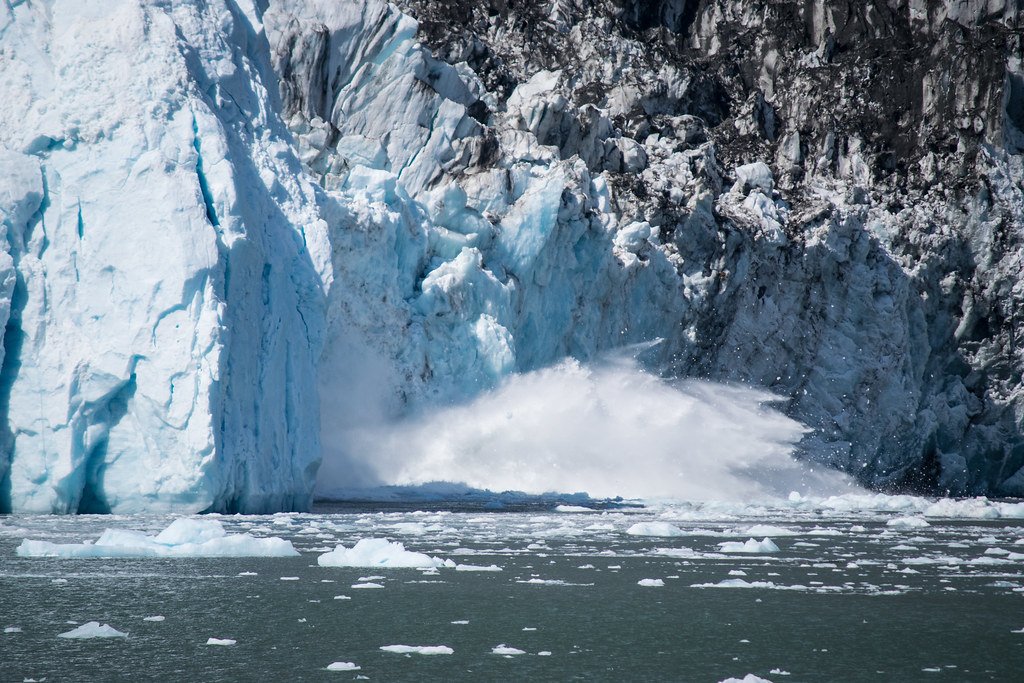

A Global Emergency Hidden in Plain Sight

UNESCO and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) have officially launched the International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation on January 21st, 2025, marking a crucial milestone in global efforts to protect these essential water towers that provide freshwater to over 2 billion people worldwide. But this isn’t just about marking calendars – it’s about acknowledging a crisis that’s literally melting before our eyes. WMO’s State of the Global Climate 2024 report confirmed that from 2022-2024, we saw the largest three-year loss of glaciers on record. Seven of the ten most negative mass balance years have occurred since 2016. Think of it like watching a massive library burn down, except instead of books, we’re losing thousands of years of Earth’s climate history. The urgency isn’t just scientific – it’s existential.

The Ice Memory Foundation’s Revolutionary Mission

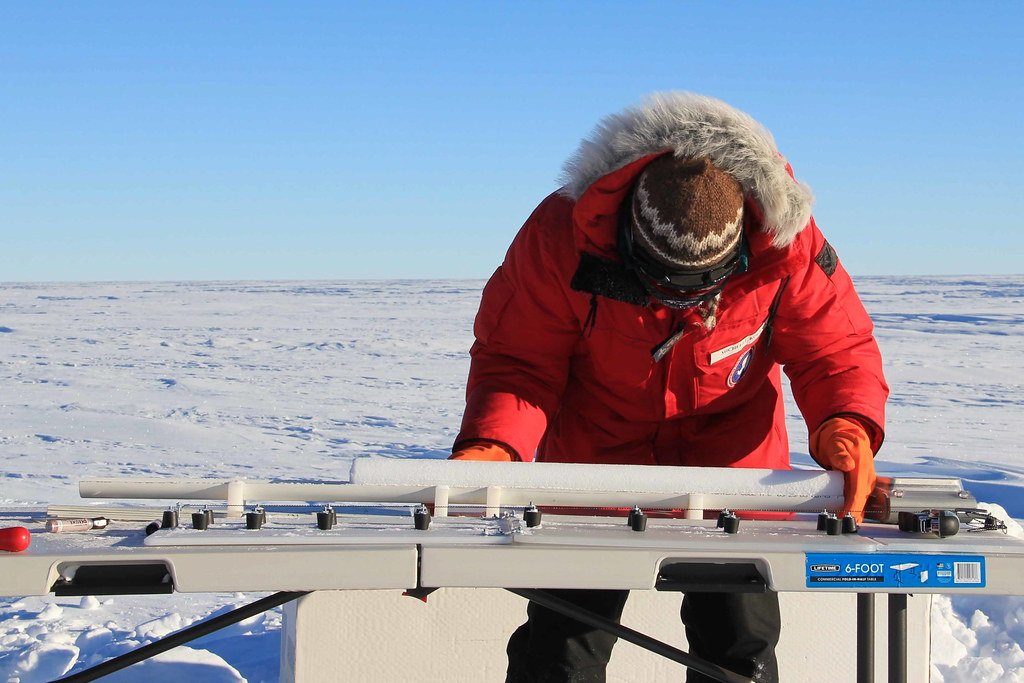

Schwikowski, an environmental chemist at the Paul Scherrer Institut near Zurich, is the scientific lead for the Ice Memory Foundation, a collaborative group that aims to preserve glacial ice records before climate change wrecks them. Their goal is to get cores from 20 glaciers around the world in 20 years, and, starting in 2025, lock them away for long-term storage in an ice cave in the Antarctic — a natural freezer that will hold them at close to minus 60 degrees F (minus 50 degrees C). It sounds like something from a science fiction movie, but it’s happening right now. The Ice Memory Foundation was officially created by seven major French, Italian, and Swiss scientific institutions in 2021: the CNRS, the IRD, University Grenoble Alpes, and the French Polar Institute (IPEV) in France; the Italian National Research Council (CNR) and Ca’ Foscari University of Venice in Italy; and the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) in Switzerland. These scientists aren’t just preserving ice – they’re preserving time itself.

When Glaciers Become Time Machines

Glaciers contain irreplaceable archives of human, environmental, and climate history, preserving crucial records of Earth’s past within their ancient ice. Imagine being able to breathe the same air that existed 800,000 years ago – that’s what ice cores offer us. Crucially, the ice encloses small bubbles of air that contain a sample of the atmosphere – from these it is possible to measure directly the past concentration of atmospheric gases, including the major greenhouse gases: carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide. Each layer of ice is like a page in Earth’s diary, recording volcanic eruptions, dust storms, even ancient forest fires. Falling snow often crystallizes around atmospheric particles such as pollen, dust, smoke, or volcanic ash, all of them preserving details about the moment each snowflake fell from the sky. We’re talking about nature’s most detailed record-keeping system, and it’s melting away fast.

The Antarctic Deep Freeze Solution

Their primary goal: create the world’s first ice archive sanctuary in Antarctica, using glaciers threatened by global warming. Antarctica is indeed the most reliable — and natural — freezer in the world. Hundreds of ice cores taken from around the world will be stored for several centuries in a snow cave at -54°C in Antarctica, at the Concordia station. This isn’t your typical storage facility – we’re talking about building humanity’s first climate vault in one of the most remote places on Earth. Although transporting the ice cores to Concordia Station requires intense logistical effort, this location is ideal in many ways: Guaranteed long-term preservation of samples with no energy consumption required for refrigeration, protecting samples from any risk of disrupted refrigeration (technical problems, economic crises, conflicts, terrorist attacks, etc.). Structured sample management combined with restrictive Antarctic logistics that prevent easy access to cores. Storage in a polar region managed via the Antarctic Treaty, signed by the world’s major nations, for which territorial claims are frozen.

The Great Transport Mission of 2025

The first Ice Memory alpine ice cores – extracted between 2016 and 2023 – will leave the laboratory cold rooms of the CNR-ISP in Italy in October. Departing the port of Trieste, they will be transported aboard the icebreaker Laura Bassi, an Italian research vessel under care of Italy’s National Institute of Oceanography and Applied Geophysics. After crossing the Atlantic and sailing to Christchurch, New Zealand, the ice cores will reach the Italian Station Mario Zucchelli in Antarctica in early December. Picture this incredible journey: ancient ice samples traveling thousands of miles from European mountains to Antarctic storage, maintaining their sub-zero temperatures throughout. It’s like moving priceless artifacts, except these artifacts contain the secrets of our planet’s climate past. The logistics alone are mind-boggling – maintaining a perfect cold chain across continents and oceans.

Racing Against Melting Mountain Archives

When Margit Schwikowski helicoptered up to Switzerland’s Corbassière glacier in 2020, it was clear that things weren’t right. “It was very warm. I mean, we were at 4,100 meters and it should be sub-zero temperatures,” she says. Instead, the team started to sweat as they lugged their ice core drill around, and the snow was sticky. This isn’t just scientists being dramatic – it’s a wake-up call from nature itself. But the core attempted from Corbassière was a failure — and has the team wondering if they are already too late. Studies of a few dozen well-monitored glaciers in the World Glacier Inventory have shown that the pace of glacial ice loss has accelerated from a few inches per year in the 1980s to nearly 3 feet per year in the 2010s. A 2023 model of some 215,000 mountain glaciers showed that nearly half of them could disappear entirely by 2100 if the world warms by just 1.5 degrees C. We’re literally in a race against time, and time is winning.

When Ice Archives Self-Destruct

In a Brief Communication in this issue of Nature Geoscience, Margit Schwikowski and colleagues show how just two years of warming has made the reconstruction of atmospheric aerosols from a Swiss glacier core untenable. They find that a large portion of aerosols have been removed from the upper part of the core, either washing away in surface runoff or migrating deeper into the glacial ice and contaminating the older record. The loss of relatively modern aerosols from the ice core means it is difficult to assess how well the sampled ice represents aerosols in the atmosphere. It’s like trying to read a book where the pages are randomly disappearing and mixing with other chapters. The warming doesn’t just melt glaciers – it scrambles their historical records, making centuries of climate data unreliable. Scientists are finding that even small temperature increases can corrupt ice cores that took thousands of years to form, turning these natural libraries into scrambled texts.

The Billion-Dollar Question: Why Now?

Based on a compilation of worldwide observations, the World Glacier Monitoring Service estimates that glaciers (separate from the continental ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica) have lost a total of more than 9,000 billion tons since records began in 1975. The 2024 hydrological year marked the third year in a row in which all 19 glacier regions experienced a net mass loss. Glacier mass loss was 450 billion tons in the 2024 hydrological year – the fourth most negative year on record. These aren’t just numbers on a spreadsheet – they represent irreplaceable climate archives vanishing forever. About 41 % of the total loss since 1976…occurred during the last decade from 2015 to 2024… During 2023 alone, the glacier mass loss was about 80 Gt [80 billion metric tons] higher than any other year on record, corresponding to 6 % of the total loss since 1975/1976. The acceleration is staggering, and every year we wait, more irreplaceable information disappears.

From Helicopters to Antarctic Ice Caves

Since its beginnings in 2015, the Ice Memory project conducted nine drilling expeditions in France, Italy, Switzerland, Bolivia, Russia and Norway (Svalbard). in 2023 at Colle del Lys / Italy, the team collected 2 ice cores of 105 and 106 m length recovering 150–200 years of planet history. Each expedition is like a surgical operation performed at extreme altitude in sub-zero conditions. Teams haul heavy drilling equipment up mountains, work in thin air where every breath is precious, and extract cylinders of ice that might contain 400 years of climate history. By drilling for two cores at each site—a “reference” core for current scientific efforts and a “heritage” core to be stored for future research—the IMF hopes to preserve valuable data for scientists years from today, when advanced technology may be able to reveal far more. It’s like having a backup drive for the planet’s climate history.

The Technology Revolution in Ice Core Analysis

New analytical techniques that allow for the extraction of new or more detailed information from old cores will also help extend the scientific potential of the ice cores we are able to harvest. With time running short, we need to save what ice we can to continue to unravel the stories trapped within it. Scientists today can extract information from ice cores that would have been impossible to detect just decades ago. Future technologies might reveal secrets we can’t even imagine – ancient DNA, microscopic organisms, or atmospheric chemistry patterns that could revolutionize our understanding of climate change. By drilling and preserving these cores, scientists can access all sorts of records, from greenhouse-gas concentrations to changes in temperature, and even 15,000 year old microbes. The data can be used to generate insights on recent human environmental impacts, or longer-term processes like Earth’s orbital movements, which influence Earth’s climate. We’re not just saving ice – we’re preserving the potential for discoveries that haven’t been made yet.

The Ticking Clock of Mountain Water Towers

High mountain regions are the world’s water towers. Depletion of glaciers therefore threatens supplies to hundreds of millions of people who live downstream and depend on the release of water stored over past winters during the hottest and driest parts of the year. Think of glaciers as nature’s savings accounts – they store water when it’s abundant and release it when it’s needed most. Meltwater is often used to compensate for the lack of rain during dry seasons. As glaciers shrink, this potential is diminished, meaning that mountain communities and their downstream counterparts will have to radically shift how they manage water resources. In the Andes, where peak water has already passed for many glaciers, communities are grappling with the impacts of unreliable water sources from both the glaciers and climate change-induced changes in rainfall patterns. We’re not just losing climate records – we’re losing the water systems that billions depend on.

From Kilimanjaro to the Himalayas: A Global Meltdown

The famed snows of Kilimanjaro have melted more than 80 percent since 1912. Glaciers in the Garhwal Himalaya in India are retreating so fast that researchers believe that most central and eastern Himalayan glaciers could virtually disappear by 2035. These aren’t distant statistics – they’re iconic landscapes disappearing within human lifetimes. The glacierized mountains of the Hindu-Kush-Himalaya region have been called the “Water Tower of Asia” since the feed some of the Earth´s most important rivers such as the Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra and Yangtze – all of which originate there in what is a relatively small area. They are considered “a lifeline for hundreds of millions, if not billions of people”. They have already lost 40 per cent of their volume since the end of the 19th century. It is predicted that 75 per cent will be lost by the end of this century. When scientists talk about the “Water Tower of Asia,” they’re describing glacial systems that feed rivers supporting nearly half the world’s population.

The Dangerous Meltwater Paradox

As a glacier begins to retreat, its ice gradually melts and increases the amount of water flowing to the river basin. With more meltwater, the risk of flooding downstream increases. In some cases, this can lead to “glacial lake outburst floods”, in which a natural dam fails and suddenly releases meltwater with devastating consequences. Eventually, the glacier experiences its highest amount of melting and produces the maximum volume of water runoff, known as “peak water”. Here’s the cruel irony: glaciers give us too much water before they give us none at all. Then there is the threat of sudden disasters, including glacial lake overflow floods (or GLOFs for short). Research has assessed global GLOF risk, with some 15 million people now living in proximity to this danger today. A catastrophic flood in Pakistan in 2022 was triggered by extreme rainfall, combined with glacial melt. That event not only claimed lives and harmed food security, it also critically damaged infrastructure and spurred water-borne diseases in its aftermath. It’s a disaster with a delayed fuse – first floods, then droughts.

The Deep Freeze Diplomacy Challenge

As the 46th Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM) concluded on May 30th, 2024 in Kochi, Kerala (India), a very important milestone has been reached by the Ice Memory Foundation. Indeed, storing heritage ice cores in Antarctica on a long-term basis – possibly hundreds to thousands of years as aims the Ice Memory Foundation – requires great attention in terms of environmental impact and a full consensus from the 57 parties of the Antarctic Treaty system. Antarctica is a unique land of peace and science, where long term governance relies on consensus of the State parties. Getting permission to store ice cores in Antarctica wasn’t just a scientific challenge – it was a diplomatic marathon requiring approval from dozens of nations. The cores will be accessible to more than 55 nations through the Antarctic Treaty Agreement, which is overseen by the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat. The remoteness and strictly controlled logistics will also allow the repository to provide access based on scientific criteria, rather than geopolitical interests. As a part of their commitment to long-term governance, the IMF plans for the foundation to be transferred to an international organization in 20 years.

The Ultimate Backup Plan for Planet Earth

But Schwikowski points out that these facilities use energy and are vulnerable to temperature fluctuations and even failure. In 2017, a rare double malfunction caused the Canadian Ice Core Archive freezer in Alberta to warm up to around 100 degrees F (40 degrees C) without triggering the right alarms. Traditional freezers are vulnerable to power outages, equipment failures, and even human error. The Antarctic solution is brilliant in its simplicity – no electricity bills, no mechanical failures, just nature’s own deep freeze. The Ice Memory heritage ice cores will be safeguarded for centuries in Antarctica. Difficult access to the samples, combined with restrictive Antarctic logistics will prevent an over-use of the cores. At last, the storage in a polar region managed via the Antarctic Treaty, prevents territorial claims as they are frozen, as signed by the world’s major nations. It’s like creating a time capsule that’s both virtually indestructible and internationally protected.

Ancient Air Bubbles Tell Modern Stories

Atmospheric carbon dioxide levels are now 50% higher than before the industrial revolution. This increase is due to fossil fuel usage and changes in land-use. The magnitude and rate of the recent increase are almost certainly unprecedented over the last 800,000 years. Methane also shows a huge and unprecedented increase in concentration over the last two centuries. Those tiny air bubbles trapped in ice cores are like atmospheric time capsules, preserving samples of