You might think that by 2026, with all of our satellites, smartphones, and artificial intelligence, we would have a pretty solid picture of the planet we live on. We’ve mapped the surface of Mars in extraordinary detail. We’ve sent probes to the edges of the solar system. Yet the vast, dark wilderness that covers most of our own world, right here beneath the waves, remains almost entirely unknown to us.

The ocean is not just a body of water. It is a living, breathing universe unto itself, home to creatures stranger than anything science fiction has ever imagined, harboring ecosystems that science is only beginning to comprehend. The deeper you go, the stranger it gets. So let’s dive in.

A World Beneath Our Feet That We’ve Barely Glimpsed

Here’s a number that should genuinely stop you in your tracks. Despite covering roughly two thirds of Earth’s surface, the deep ocean remains largely unexplored. In decades of deep-sea exploration, humans have observed less than 0.001% of the deep seafloor. That total area is roughly the size of Rhode Island. Let that sink in for a moment.

Only about 20% of the ocean has been explored at all, meaning more than 80% of it remains completely unknown to us. Because it is so difficult to protect what we don’t know, only about 7% of the world’s oceans are designated as marine protected areas. Think about what that means for the millions of species that may be living their entire lives in a world we have never even seen.

The Crushing, Pitch-Black Challenge of Getting Down There

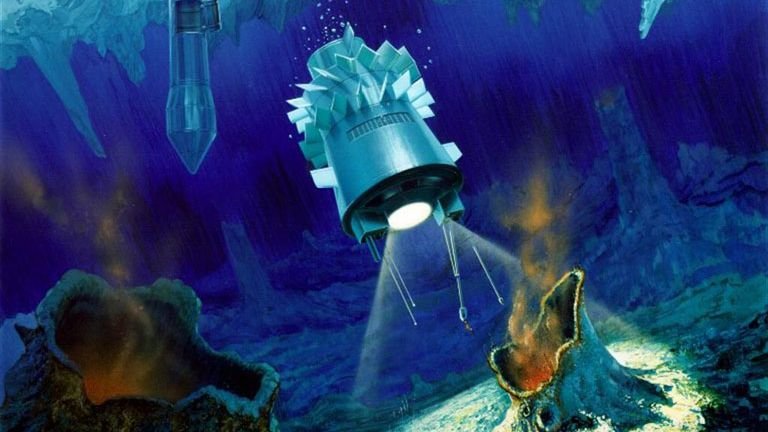

One of the biggest challenges of ocean exploration comes down to physics. At great depths, the ocean is characterized by zero visibility, extremely cold temperatures, and crushing amounts of pressure. It is not a dramatic exaggeration to say that exploring the deep sea is, in some ways, harder than exploring space.

On a dive to the bottom of the Mariana Trench, which is nearly seven miles deep, you are talking about over 1,000 times more pressure than at the surface. That is the equivalent of the weight of 50 jumbo jets pressing on your body. No wonder we’ve seen so little. The ocean is not secretive by nature. It is simply extraordinarily difficult to reach.

A Staggering Number of Species Still Waiting to Be Found

The ocean covers 71% of our planet, yet it is said that only around 10% of marine life has been discovered so far, leaving an estimated 1 to 2 million species still undocumented. That is not a small number. That is a biological library so vast it boggles the mind, sitting in the dark, waiting for someone to open the door.

Roughly two thirds of these species, possibly more, have yet to be discovered or officially described, with almost 2,000 new species accepted by the scientific community each year. Every single year. And the pace is only increasing as technology improves. Honestly, it makes you wonder what is swimming around down there right now, completely unknown to science.

Recent Expeditions Are Rewriting the Rulebook

The Nippon Foundation-Nekton Ocean Census, the world’s largest collaborative effort to accelerate the discovery of marine life, recently announced the discovery of 866 new marine species. This is a significant step in advancing our understanding of ocean biodiversity, with discoveries expected to grow as the programme continues. Eight hundred and sixty six new species, found in a single program. That tells you everything about how much is out there.

Using divers, submersibles and remotely operated vehicles, new species have been identified from depths of 1 to 4,990 metres. The discoveries encompass dozens of taxonomic groups and include new species of shark, sea butterfly, mud dragon, bamboo coral, water bear, octocoral, sponge, shrimp, crab, reef fish, squat lobster, pipehorse, limpet, hooded shrimp, sea spider and brittle star. That list reads less like a scientific inventory and more like the cast of a fantasy novel.

The Bizarre, Wonderful Creatures Living in Total Darkness

The deep sea, defined as ocean depths below 200 metres, encompasses vast and largely unexplored habitats such as abyssal plains, hydrothermal vents, cold seeps, and ocean trenches. This environment supports a remarkable diversity of life forms adapted to extreme conditions, including high pressure, low temperatures, and complete darkness. Life finds a way, as they say, and in the deep ocean, it finds ways that defy our most basic assumptions about what living things can tolerate.

In 2024, MBARI researchers described a remarkable new species of nudibranch from the depths of the midnight zone. Nicknamed the “mystery mollusc,” it swims with a fingered tail and uses a cavernous hood to capture food. MBARI technology is providing vital information about deep-sea biodiversity so resource managers and policymakers can make informed decisions about the future of the ocean. If that description sounds like something from a fever dream, wait until you hear what it does next. If threatened, the mystery mollusc can light up with bioluminescence to deter and distract predators. On one occasion, researchers observed the animal illuminate and then detach a steadily glowing finger-like projection from its tail, likely serving as a decoy.

Hydrothermal Vents: Cradles of Life in the Abyss

Deep-sea hydrothermal vents are underwater geysers that release superheated water rich in minerals, creating entire ecosystems where life thrives without sunlight. The discovery of these vent systems fundamentally changed what scientists believed was possible for life on Earth. Before vents were found, sunlight was considered an absolute prerequisite for complex ecosystems. The deep sea proved that wrong in spectacular fashion.

Hydrothermal vents are thought to be the birthplace of life on Earth because they provide the necessary conditions: they are stable, rich in minerals, and contain sources of energy. Researchers recently discovered even more hidden vent systems. Beneath the waters off Papua New Guinea lies an extraordinary deep-sea environment where scorching hydrothermal vents and cool methane seeps coexist side by side, a pairing never before seen. This unusual chemistry fuels a vibrant oasis teeming with mussels, tube worms, shrimp, and even purple sea cucumbers, many of which may be unknown to science.

The Deep Ocean as a Pharmacy and a Promise

Marine bioprospecting, which involves the exploration of genetic and biochemical material from marine organisms, can be used towards addressing a broad range of public and environmental health applications such as disease treatment, diagnostics and bioremediation. The deep ocean is not just a biological curiosity. It may be one of the most important natural medicine cabinets on the planet.

Among recent discoveries is the gastropod Turridrupa magnifica, a remarkable predator from the waters of New Caledonia and Vanuatu, one of 100 newly identified turrid gastropods. Equipped with venomous, harpoon-like teeth, these deep-sea snails inject toxins into their prey with precision. Related species have already contributed to groundbreaking medical advancements, including chronic pain treatments, and hold promising potential for cancer therapies. A snail from the abyss, helping cure cancer. It’s hard to say for sure where the next breakthrough will come from, but the ocean seems like a very good place to look.

The Race Against Time: Mining, Climate, and Vanishing Ecosystems

The expansion of deep-sea mining in 2025 is raising serious concerns about habitat destruction, biodiversity loss, and disruptions to oceanic carbon storage. You are reading this in a world where we have barely scratched the surface of what the deep ocean holds, and yet powerful interests are already pushing to extract minerals from the seafloor at industrial scale. The timing could hardly be worse.

In a landmark study, macrofaunal density decreased by 37% directly within mining tracks, alongside a 32% reduction in species richness. Those are not small numbers. Deep-sea scientists note that the majority of biodiversity in the deep sea lives on the metallic nodules targeted for extraction, structures that take millions of years to form. Much of the marine life also lives in the upper sediment layers, which are permanently disturbed during mining. Exploratory dredges show these ecosystems do not recover, even decades later. We would be destroying libraries we have never read.

The New Era of Exploration: Technology Lighting the Way

Using divers, submersibles, and remotely operated vehicles, new species have been identified from depths of 1 to 4,990 meters, with analysis conducted by collaborating scientists from the Ocean Census Science Network. The tools are getting better every year, faster and cheaper and more capable than anything that came before. Think of it like going from a single flashlight to floodlights illuminating a football stadium.

Remarkably, over 65% of visual observations have occurred within 200 nautical miles of just three countries: the United States, Japan, and New Zealand. Due to the high cost of ocean exploration, a mere handful of nations dominate deep-sea exploration, with five countries responsible for 97% of all deep-sea submergence observations. That kind of geographic bias means entire ocean regions, full of life that nobody has ever seen, are still completely untouched by science. Researchers are working on the development of a new deep ocean research and imaging system that will cost on the order of only a few thousand dollars, bringing down the cost and increasing the usability of these kinds of tools, which could be a real game changer for the deep-sea community worldwide.

Conclusion

The ocean is Earth’s great frontier, and what we know about it barely fills a thimble compared to what is waiting to be found. You live on a planet where creatures armed with harpoon-like venom teeth, glowing decoy limbs, and chemosynthetic metabolisms are alive right now, going about their business in total darkness, completely unaware of our existence. That is not a metaphor. That is just Tuesday, somewhere below 3,000 metres.

The tragedy would not be in failing to find all of it. That would take centuries. The real tragedy would be in destroying it before we even knew it was there. Protecting the deep ocean is not just an environmental issue. It is arguably the most consequential act of intellectual self-preservation our species could undertake. The question is not whether the deep sea holds answers to some of our biggest questions about medicine, climate, and even the origin of life itself. The question is simply this: will we be wise enough to look before we dig?